Exploring the ancestral history of the steelband movement

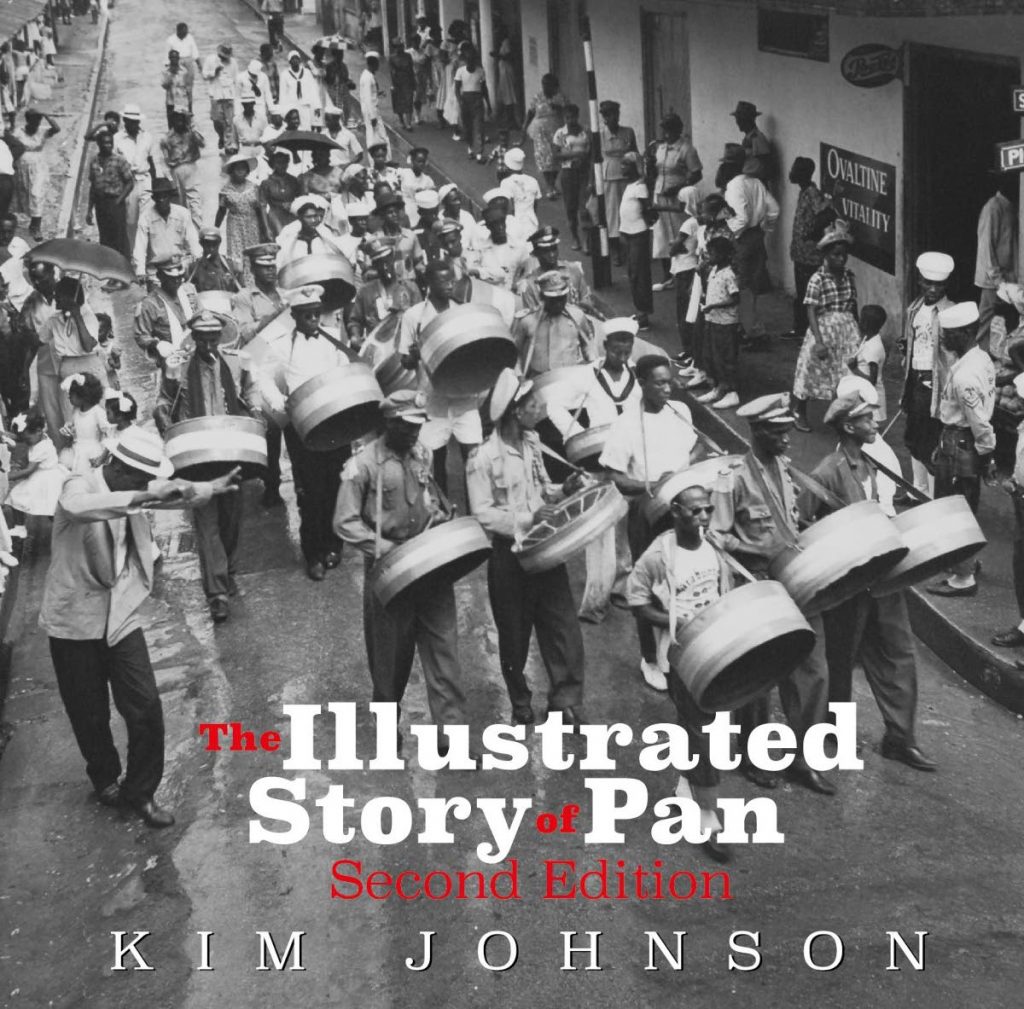

In the second edition of his definitive book on the steelband, The Illustrated Story of Pan, author Kim Johnson increases the page count by just 12, but the work feels more expansive than the first edition, which I recall only from flipping through it soon after its first publication.

This work is immediately more engaging. Johnson has used his pages to excellent effect and the design of the spreads, credited to the author and artist Ayo Ledgerwood, delivers an effective mix of first-person quotations, big photographs and the historical text that knits them together.

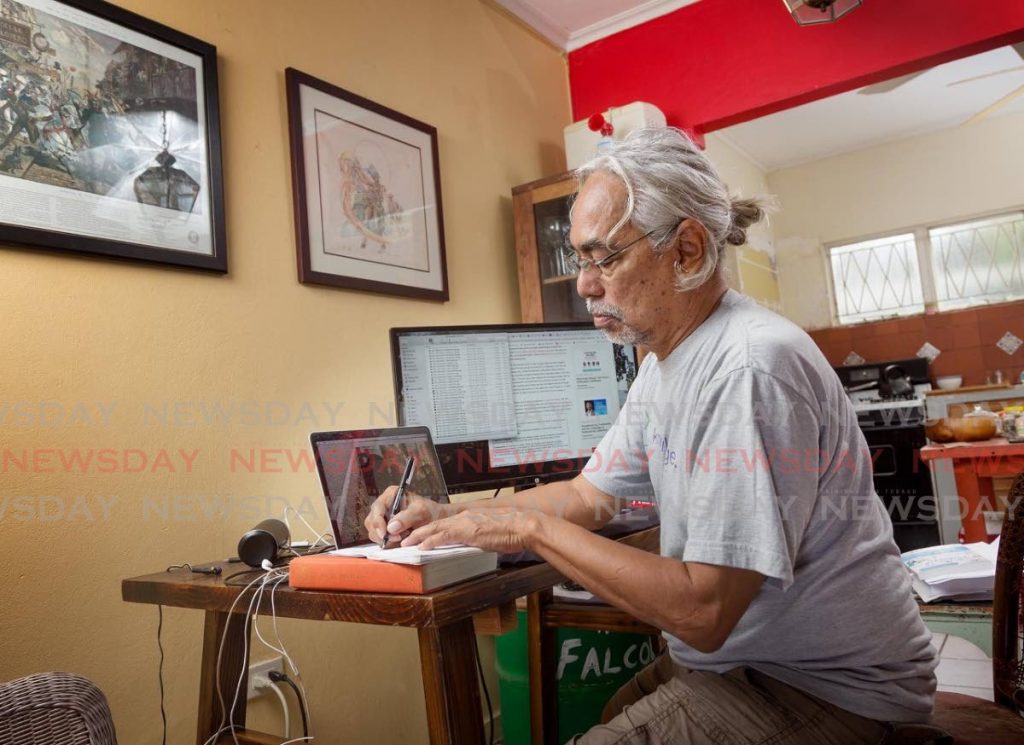

The book is the result of decades of research into the history of the steelband’s development, which began as more than 100 articles on pan written by Johnson when he was at the Sunday Express in the 1990s. Editor Lennox Grant had endorsed the “investment in shoe-leather,” as he put it at the time, that gathering these stories demanded.

Johnson began scanning the photos his subjects and others showed and sent him and eventually gathered a collection of more than 3,500 photos related to the development of the steelband. Less than a tenth of them are included in the book, all strategically chosen to echo and amplify the words they are framed by.

As photographs, they are, individually, unimpressive, hardly first choice for a coffee-table book driven by photography. Most were captured by tangentially interested observers and are, in the most accurate use of the term, snapshots. They lack sharpness and tonal range – but deliver a direct and intimate discovery with their subject matter.

Their true power is as a curated collection, the individual frames piecing together a wide-ranging collage that brings sight to the emergence of art from Carnival’s chaos of camaraderie.

The result is what Johnson describes as “a family album,” a collection of photos and stories that read like a forgotten ancestral story, populated by people we kind of know, telling a story that is both familiar and new. There is something transcendent about this collection of images, an alchemy of arbitrary snaps, group portraits, documentary images, touristy fantasy and posed promotional images.

The photographers are also, for the most part, anonymous. Their names and intersections with the people and places pictured lost to time and fragile memory. Those who are identified include Franklin Barrett, a US Navy serviceman posted to Trinidad, the actor/singer Edric Connor, Commander Jack Williams and others with the mix of curiosity and equipment who turned their lenses on the scrappy and evolving Carnival celebration.

Some of the very earliest photos are little more than postcards, culture recorded in the service of exotica.

On first skimming through the work, what jumps out is the enormous scale of its component parts. This is an artful merging of all the resources Johnson collected into a work that hammers a piton of authority into the hardened cliff face of indifference that is the fate of all our histories.

It took me weeks to read this book, not because there are so many words, but because of the engaging resonance that the author has managed to strike. The attentive reader cannot help but bounce between the formal history, the personal recollections and the photographs on each page, back and forth, like the constant sounding of a note in search of perfection.

What emerges is something beyond the words, an understanding of the quixotic fight to turn garbage – discarded tins and drums into instruments – hammering, no, beating music out of containers and turning trash into treasure.

From the scruffy circumstances offered up by the photos, from the harrowing, often salty stories retold by the players and observers who lived this history, there emerges a powerful understanding of a people who demanded music and proceeded to pound it out of their environment.

Steeldrums were an unlikely basis for a musical instrument, but became the only object that could stand up to the insistent pressure of invention of this effort to make music out of nothing.

In parallel with all this is the story of the increasing politicisation of the movement, encouraged and guided by Dr Eric Williams. At his very first meeting with panmen in 1955, Williams told them that politics was in everything. It would become a guiding truth of the growth of the movement and its intersection with the physicality of politics of the late 50s and 60s.

It would also fundamentally change steelband’s evolution, particularly after Williams formed the Steelband Improvement Committee, a government agency liaison with the movement that would eventually become the eternally compromised Pan Trinbago.

It’s here that the project demands a second volume. So much gets crammed into the last hundred pages that it seems rushed compared to the patient and considered historical dissection of the lost and certainly scattered early history.

The author’s grappling with the recent history of the steelband becomes even more pronounced with his effort to articulate a manifesto for pan in the final chapter. The competing interests, new, mercurial talent and the volatile politics of modern pan don’t conform readily to any lucid or readily accessible prescription. The only thing that seems always to have been true of pan is its own internal conflicts.

Even Johnson’s despair over Facebook and inward-facing social media engagement got flipped during the last year, as those virtual connections became a lifeline for the movement and its practitioners. Neither a pandemic nor Panograma (a virtual pan competition) was on his radar when this book was being completed.

A growing number of next-generation, music-literate pan musicians are coming of age, and they don’t fit easily into the old roles that pannists created for themselves. What they take for granted was unimaginable at the dawn of the instrument’s creation.

Pan’s children are the ones who really need to read this book, to truly understand how their instrument was willed into existence, to find context for their often puzzled elders and to chart a future that honours its considerable history.

The Illustrated Story of Pan, launched on Indiegogo, is available for US shoppers at santimanitayblog.com and for the rest of the world through shopcaribe.com.

Local buyers can get the book from Paper Based Bookshop, Metropolitan Book Suppliers and Nigel R Khan bookstores.

Comments

"Exploring the ancestral history of the steelband movement"