The Caribbean broadband development dilemma

BitDepth#1493

A NEW report, Gigabit Caribbean by Danish telecom consulting firm Strand Consult, was released in December 2024. It explores the challenges faced by operators and governments in driving investment in fixed and mobile networks in the Caribbean.

Strand surveyed most of the Caricom Caribbean except for Haiti, and sought perspectives from most large-scale operators in those countries.

The report does not break out evaluations or statistics for individual nation states, but the aggregate findings reflect current concerns about how to finance next-generation networks in the region.

The concept of a gigabit society was introduced by the European Commission in 2016 to describe a drive to very high-capacity networks that matched consumer shifts to internet-based communications, as well as the need to extend connectivity to rural and remote areas.

Strand suggests that a successful Caribbean gigabit society is one that implements 5G mobile broadband networks and fibre to the home (FTTH) download connections of at least 100 megabits per second (Mbps) by 2030.

In 2023, 5G networks accounted for just one per cent of all internet connections in the Caribbean.

According to the report, 1.6 million Caribbean households have a FTTH connection and 553,681 households are passed by a fibre connection but don't subscribe. More than a million households have no fibre connection and the cost of connecting these households is estimated at US$2.5 billion.

That isn't the only gap. Average revenue per user in Caribbean mobile broadband networks is around US$10 per month. While mobile broadband is generally pervasive in the region where it is available, the cost of even a basic FTTH connection is US$50 per month.

The International Monetary Fund sets GDP per capita for the region at less than US$13,000 per person. Using a monthly budget for communications of two per cent of income as a yardstick, just US$21 is available for a FTTH connection.

Broadband connections priced to cover investment costs are likely to double that fee.

Operators surveyed for the report noted that further development is limited by the challenge of recovering capital expenditure. There is no clear return on investment for high investment costs, particularly in rural areas that aren't served by electricity.

Where is the development money to come from?

If operators cannot recover the costs of investment from end users, the conversation inevitably turns to services that make disproportionate use of established networks as sources of revenue.

Globally, 80 per cent of internet traffic is video-streaming entertainment. Efforts at persuading the providers of these services, as well as other services that are implemented by free riders on existing broadband connections, such as voice and video calls on messaging services, have failed in the Caribbean.

The report references the development of South Korea from an agrarian society to an industrial powerhouse and its leveraging of robust broadband connectivity as a backbone of that development, beginning in 1994.

South Korea brought half of its population online by 2002 and began rolling out 100 megabit service in 2006. Driven by this online capacity, two native services platforms, Kakao and Naver, became a robust presence in the country.

The country's ubiquitous connectivity provided a basis for a robust cultural economy that includes K-Pop groups and Korean dramas, both of which have been successfully exported to global audiences.

Korea is considering the European Union's Digital Markets Act as a model for extracting revenue from streaming services.

The Korean Free Ride Prevention Act attempted to bring market-based negotiation between broadband providers and the largest generators of network traffic.

In Korea, the largest network traffic, 41 per cent, is generated by Google, Netflix, Naver, Meta and Kakao.

SK Broadband and Netflix have jousted in court since 2020 over infrastructure improvements totalling US$40 million incurred by the internet provider after Netflix demand jumped by more than 26 per cent in the country.

The contretemps was eventually settled with a backroom agreement in September 2023, but it's a country-specific case, since Netflix leans so heavily on South Korean content for its services.

Conversations about the free ride that over-the-top (OTP) players have enjoyed in the Caribbean for more than a decade continue, but the response from streamers and services remains unsatisfactory.

Price competition in the best wired countries in the region is a disincentive for further investment in telecommunications infrastructure. Most remote areas eventually get service either through Universal Service Fund projects like those sporadically implemented in TT or through breakthrough technologies like Starlink's satellite connections.

The status quo is a price-driven stalemate between sunk costs and customer spending reluctance that's unlikely to be broken by anything short of new competitor investment in more advanced technologies.

Request the report here: https://cstu.io/fcdfe6.

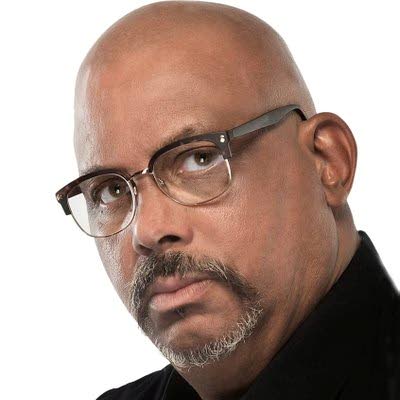

Mark Lyndersay is the editor of technewstt.com. An expanded version of this column can be found there

Comments

"The Caribbean broadband development dilemma"