Put the pawi on the money

Faraaz Abdool makes a case for the indigenous and endangered pawi to be the bird on our highest currency note

Here in Trinidad and Tobago, we are immensely lucky to have some of the most beautiful currency notes in the world. Adorned with artwork and security features, our notes are periodically updated to reflect culturally significant facets of our lives.

One of the most biodiverse places on the planet, ours is one of only two countries in the world to have two officially recognised national birds: the scarlet ibis and the rufous-vented chachalaca or cocrico. Our Coat of Arms is adorned by a trio of hummingbirds from the 18 species found here. Birds are also prominent in our currency, with the front of each note featuring a different bird!

Although we gained independence and our own currency in 1962, it was only after the second revision in 1977 that the first birds were introduced on the bills. At this point, not every note had a bird either. The $5, $20, and $100 bills featured flowers and plants; namely the chaconia, hibiscus, and coffee, respectively. In 1985 there was another revision, and this time all denominations featured birds.

The currency notes now feature scarlet ibis $1; Trinidad motmot $5; cocrico $10; hummingbird $20; masked cardinal $50. The only foreigner the greater bird of paradise is on the $100; and on the five cent coin (the only coin depicting a bird since the one cent – scarlet ibis – is no longer in circulation). This resplendent creature is native to the island of New Guinea and the neighbouring Aru Island chain in the Indian Ocean. The history of its arrival in Little Tobago is told in the sidebar here.

Let’s go back in time to the Victorian Era trend of decorating with colourful feathers – or even the taxidermed corpses of entire birds. This resulted in the industrial scale extermination of entire breeding colonies of birds, black grouse from Scandinavia, pheasants from China, along with crowned pigeons and birds-of-paradise from New Guinea. This practice of decorating clothing with feathers was so ubiquitous that it was even used by the British Army as part of their uniforms until 1889. This was only three years after it was noted that an estimated five million birds were being killed each year for their feathers.

At the turn of the 20th century, however, various conservation organisations were pushing back against the thirst for plumes. By the mid 1900s, the flow of feathers into Europe was in decline. While this decline began due to a scarcity of birds, it was accelerated by the conservation pushback. In 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act was enacted that granted full protection to more than 1,000 species of birds in North America, including both live and dead birds, eggs, nests, and most notably, feathers.

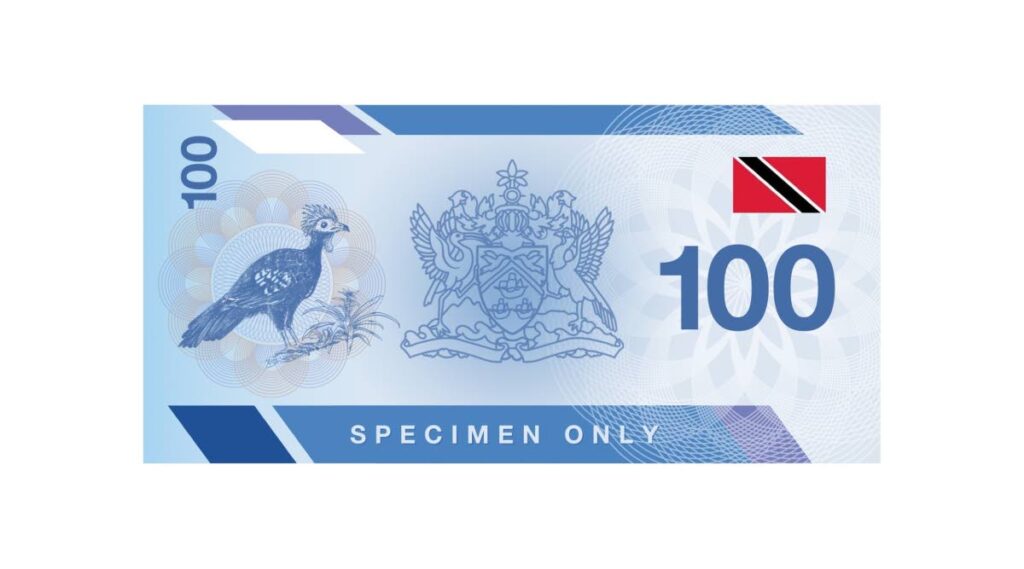

Four years after the last of the colony on Little Tobago, in 1985, a depiction of a greater bird-of-paradise was introduced in the currency of TT. Additionally, a subsequent revision to the currency in 2002 saw an introduction of a new security feature on every bill – a watermark featuring the silhouette of a greater bird-of-paradise. Evidently, there was something incredibly significant about this bird, despite not having been seen on Little Tobago for almost two decades. A later revision in 2006 saw the watermark being changed to reflect the individual birds on each denomination. Surely, there’s a better candidate for the $100 bill.

An indigenous and endangered choice for $100 bill

Of the near 500 species of birds that have been recorded since the earliest days of ornithological exploration here, one has the ominous cloud of extinction looming over it. That species is found only on Trinidad, with possibly no more than 300 birds left on the planet, teetering at the edge of existence.

The Trinidad piping-guan, locally known as the “pawi” has been officially listed as Critically Endangered according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. There is only one stage between Critically Endangered and Extinct, that being Extinct in the Wild. Consequently, the situation of the pawi is as dire as it gets. Many concerned citizens have mobilised educational campaigns and other efforts to conserve the species, its main threats being hunting and habitat loss.

Formerly found throughout forested areas on the island, it has declined steadily due to hunting began over the last 100 years. It achieved protected status within a year of the nation’s independence, but this status did little to stem the flow of bullets.

The last sighting of a pawi from east-central Trinidad was in 1983; they disappeared from the legally protected Trinity Hills Game Sanctuary in 1994. By this time, the population had plummeted to approximately 100 birds, this grave statistic galvanised some sterling conservation efforts on the island. Today, with greater awareness and an apparent reduction in poaching, the celebrated endemic Trinidad piping-guan is now on a slow but deliberate increase within the Northern Range.

We must be careful not to celebrate prematurely, as genetic studies indicate that there is incredibly limited genetic variation within the population which can negatively impact the overall health of the species as well as its ability to properly rebound from such low numbers.

For a species garnering such attention locally and internationally, relatively few Trinbagonians have had the opportunity to see one of these birds. Awareness of the criticality of the situation is imperative to prevent unfortunate occurrences such as accidental killings or triggers pulled in ignorance. We all deserve to know and understand how precious – and precarious – this bird is. The consideration of how the image of the pawi could be able to reach the maximum number of people has a singular conclusion: currency.

The public recognition and appreciation of an endemic species facing extinction would be a noble act to parallel that of Sir William Ingram over a century ago. We can continue a legacy of action with the intention of protection and preservation. The replacement of the greater bird-of-paradise by the Trinidad piping-guan would speak volumes to national pride. We can put the money on conservation action while maintaining a sense of currency in our currency.

Sidebar

Little Tobago: Questionable Sanctuary for the greater bird-of-paradise

Sir William Ingram purchased the island of Little Tobago and intended to use the former cotton plantation as a sanctuary for the greater bird-of-paradise that was being hunted to oblivion in its native range. In 1909, 56 greater birds-of-paradise were shipped to Little Tobago via England. Naturally, some birds did not survive the journey.

Maintaining the alien birds proved to be a daunting task. At the point of release, it was not possible to determine the sex of the birds, as the juvenile plumage of both males and females was identical. It was only when the birds became mature that the males would take on their famous and spectacular plumage. While the birds adapted to the fruit on Little Tobago, the island’s lack of a dependable water source meant that human caretakers were tasked with bringing water from mainland Tobago for the birds. Additionally, at least one caretaker would boast of the number of hawks he shot, despite the hawks not once preying on the birds-of-paradise. An ironic twist, given that the purpose of birds-of-paradise on the island was a conservation-minded one.

While there were accounts of increasing numbers of young birds, the various caretakers on the island were unable to find a single nest. Granted that in their native habitat, the nest of a greater bird-of-paradise is an inconspicuous structure in the fork of a large tree – it follows that if the appropriate foundation for this type of nest was not present on Little Tobago, the birds may have adjusted their strategy.

By the time Hurricane Flora barrelled into the island as a category 3 storm in 1963 the population was reduced to somewhere between 15 and 29 birds. A ten-month census from 1965 into 1966 revealed that the population had further dwindled to no more than seven birds. Although these incredibly beautiful birds had demonstrated their ability to find food, shelter, and even breed on the minuscule and very dry island of Little Tobago, oceans away from their original home, their time under the warm Caribbean sun was coming to an end. The last recorded sighting of a greater bird-of-paradise on Little Tobago was in February 1981.

Comments

"Put the pawi on the money"