Brian Ashing unveils the Nature of Power

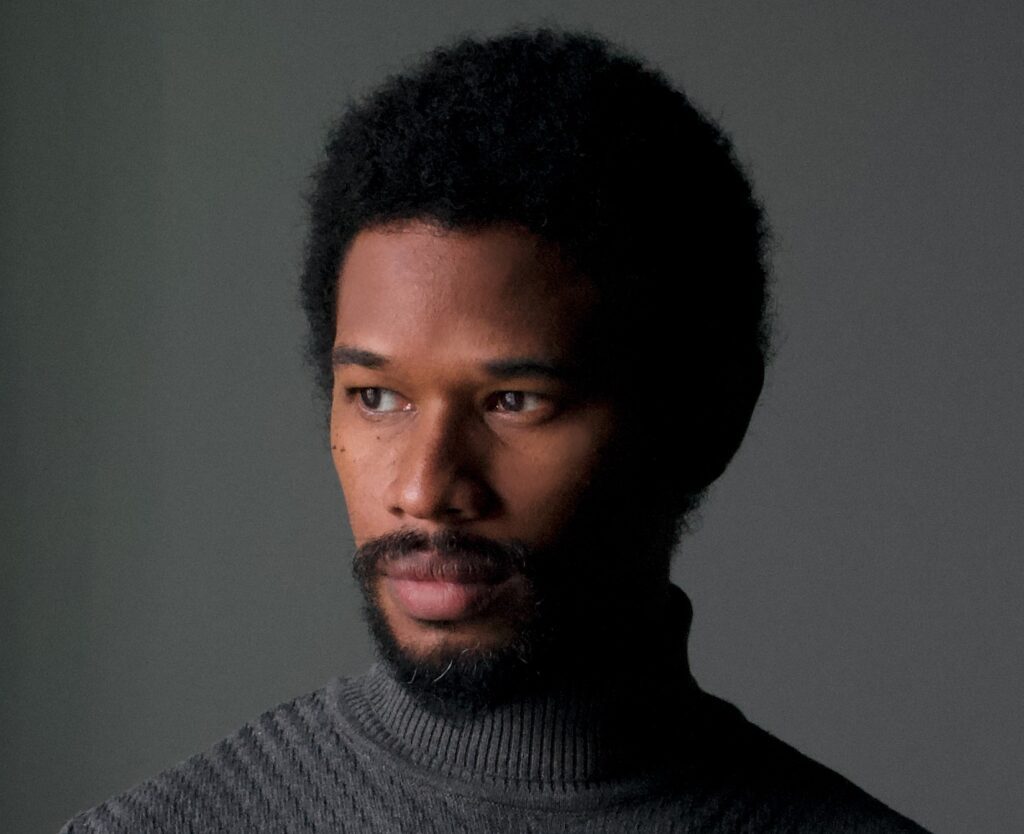

HASSAN ALI

THE theft of primordial fire is a longstanding trope in myth and art. Those among us who were inspired by Rex Warner’s Men and Gods have likely encountered the story of Prometheus.

For those who haven’t, here’s the summary: Prometheus stole fire from Olympus – specifically from Hephaestus’ (the blacksmith god) forge – and brought it to humans. As punishment for his theft Prometheus was bound to a stone where an eagle would eternally peck at his liver. It’s specifically important to note where this fire came from: not just from a divine source, but from a divine embodiment of creation and ingenuity.

Fire, in the Promethean story, is what illuminates the human mind and enables understanding; it’s also a tool of transformation (think not only of blacksmiths but of chefs, candles, and bushfires). Summarily, what Prometheus gave us was power. If this all still sounds Greek to you, think of Prometheus as the serpent in Eden and think of the fire as the fruit.

Brian Ashing’s third solo show The Nature of Power draws on this symbolic heritage and plays with fire as motif.

In Ceremonials 2, a singular egret stalks a burning marsh – its wings lifted in preparation for flight. Above the egret, a conflagration cuts the painting in two. In the lower half, around and near the egret, the fire casts its reflections forebodingly into the marsh; in the upper half, the sky is filled with orange and yellow smoke – just above the smoke, orange-tinted white egrets are flying away.

Lady Armageddon, just about two steps away from Ceremonials 2, depicts a female figure who seems to be commanding fire to rain down onto a coastal scene. The female figure is poised and bears no discernible expression beyond indifference. Considered together, both pieces come as warnings of the destructive nature of power when wielded anthropocentrically.

Certainly, excluding natural disasters and religious considerations, power has long been an anthropocentric idea. Whether we imagine ourselves as chosen by some deity to have full agency within and over the world or as simply the lucky ones in the genetic-evolutionary lottery, it’s clear to see that humans have shaped the world more than any other species.

As the catalogue for the show notes, the artist has created his own mythos in his exploration of power. For the most part, the paintings feature human characters: the twin ladies of Destiny and Damnation, the sphinx-like woman-ibis The Riddle, all the men in the male nudes that take up most of the gallery's northern wall. However, none of these human figures appear to be using their power for creation.

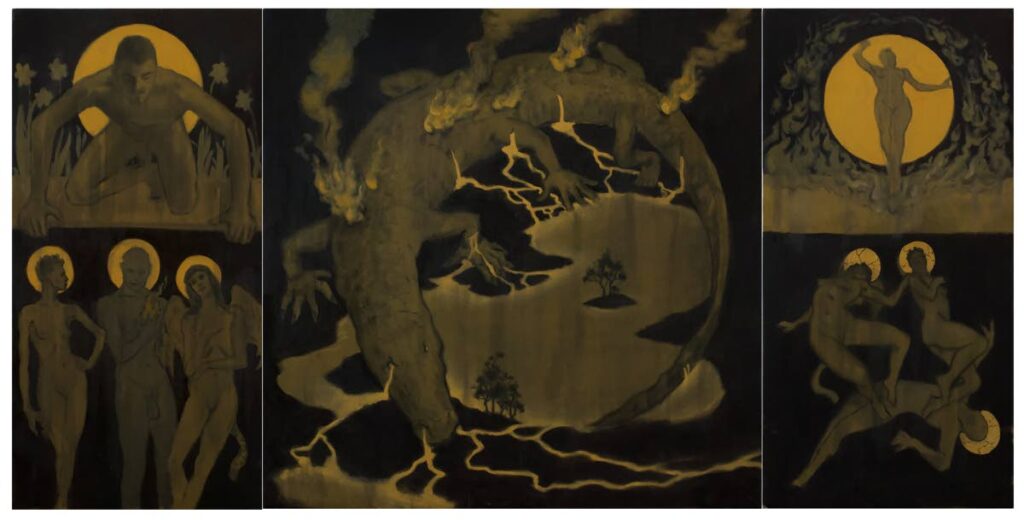

In the titular, two-toned triptych we do get to see some representation of creation. The first panel shows a male figure grovelling among flowers; beneath him are three other figures, all human-looking. The middle figure holds a flame – there’s a hint of a smirk on his face. All of these figures have golden halos.

The middle panel shows a caiman with six limbs – two pairs of human arms and one pair of human legs – twisted into a circle, bleeding lava and fire over mountains and into a lake.

The last panel shows a female figure almost completely contained within a sun-like disc basking in flames; beneath her, the three figures from the bottom half of the first panel are shown in disgrace with cracked halos – their falling bodies, reminiscent of Gustave Doré’s illustrations of Lucifer’s plummet from heaven. It’s telling that the only thing that appears to encourage life is the caiman – the non-human thing.

Furthermore, it’s important to note that the caiman is wounded: these figures have likely stolen this fire from the caiman.

We first learn power from nature: it could be from a hurricane tearing houses apart or from your first bachac bite. The six-limbed caiman is nature’s stand-in here; Those human figures with their broken halos are those whose hubris, whose desire for the power of creation, has burdened them with the knowledge of, and a proclivity for, destruction.

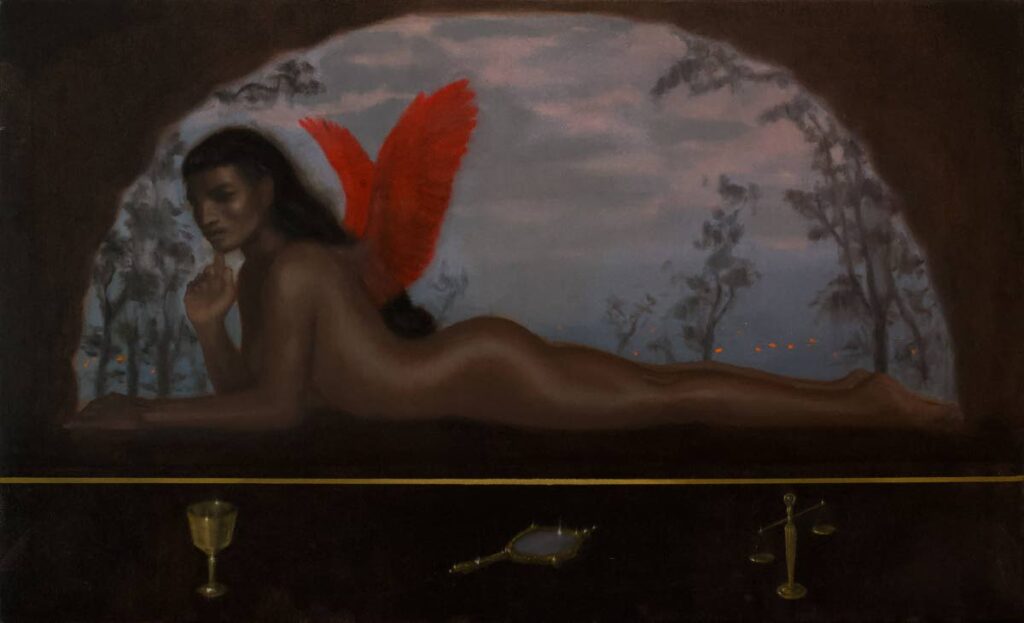

The Riddle, features three symbols which recur throughout the show: there’s the cup from Transformation; the mirror from Beauty; and the tipped scale from Chaos. All three symbols are featured in Destiny and Damnation. In a promotional Instagram post, the artist shares a riddle featuring each of these symbols in a panel by itself with a riddle of his own creation:

“I am a wine ne’er quenching thirst Yet many sip from my chalice with vigor Libra’s sigil overturned A fool’s gaze trapped in a shattered mirror What am I?”

The answer, obviously, being power. In their solo pieces, each of these symbols is filled with fire – nods to how power can intoxicate, beautify, transform and ruin.

Ashing’s previous work has primarily been portraiture. He manages to transfer the technical skills he’s learned from years of bodily representation to create beautiful figures and landscapes while also creating a more symbolically-loaded body of work than he’s done previously.

This is not to say you’ll bust your skull attempting to understand the work – it’s (symbolically, not technically) simple. Perhaps this simplicity is thematic – meant to imply something essential, classical about the exhibition’s message – but it’s difficult to not see that power and its symbols have changed in the (roughly) 2000 years between now and antiquity. Ultimately, Ashing’s offerings are reminders – not revelations.

As said before, the work is beautiful and Ashing’s painting skills are on full display. The show is open to the public at LOFTT Gallery (63 Rosalino Street, Port of Spain, above District Cafe) until November 15.

LOFTT’s gallery hours are 10am to 6pm Tuesday-Friday and 11am to 4pm on Saturdays. The artist talk, in which Ashing will be in conversation with Che Lovelace, is November 9, 6pm-8pm.

If you like the images you’ve seen from the article, I certainly suggest that you do everything in your power to catch it while you can.

Comments

"Brian Ashing unveils the Nature of Power"