South African jurist advises: 'Make laws to tackle societal ills'

SOUTH African jurist Justice Edwin Cameron says constituency representation balanced by proportional representation allocation after the election may be the best sort of system for his country and Trinidad and Tobago.

Speaking at the Judicial Education Institute of TT’s 10th Distinguished Jurist Lecture at the Hall of Justice, Port of Spain, on June 18, he offered some wisdom on constitutional reform from his experiences in South Africa after apartheid.

He said in South Africa, people voted for parties, not the individual. But, in interpreting the Constitution, five judges made the decision to include provisions for independent candidates in parliamentary elections.

However, he said there should be a clause in the constitution to hold MPs to account and challenge them if they were insufficient or inattentive.

Chief Justice Ivor Archie agreed, saying there was a situation in TT in the past where a political party got almost 200,000 votes but did not win a seat.

“There is a sense among some people that, ‘Are these people voiceless?’ So a system that would allow candidates from that party, even though they did not get through in the first pass, to, in the post-election at least, have some allocation or something.

“And it will also, I think, allow you to bring persons into the parliamentary space who have the ability and the knowledge to make very, very valuable contributions to the debates and the development of legislation,” Archie said.

Cameron stressed that legislative drafting and constitutional drafting were important opportunities.

“You don’t want to perpetuate the society that you’re making a constitution for. You want to offer it avenues to reform itself. And what are the injustices of a society – racial, class-based, capital accumulation, income, distribution, land? What are the injustices that you recognise, and how can you make a constitution that will enable those to be ameliorated at least and even eradicated?” he asked.

He advised law students, young lawyers, legal societies, civil-society organisations, religious organisations, trade unions and others to get involved to make an appreciable impact on the process of adopting a new constitution.

“Don’t leave it to the lawyers and don’t leave it to the judges only.”

He said no constitution was self-executing. He said even after apartheid, civic activism did not dissipate and principled action by civil society, independent media and brave judges continued to make a difference.

Addressing why a South African could talk about constitutional reform in TT, he said South Africa shared a similar history of “colonial subordination” which included slavery and “extractive plundering,” but colonialisation allowed for a rich legacy of racial and cultural diversity in both countries.

Also, competing claims to resources were often made along cultural and racial lines and would be best mediated through a constitution, and the Privy Council was the ultimate court in both countries, although South Africa abolished it in 1950.

“The Privy Council sometimes seems to have a lack of converses or comfort with the forging, large interpretive of meaning to constitutional phrases.

“Secondly, the Privy Council has shown a disinclination to heed or care for voices from the Caribbean itself, and dissenting voices from within its own ranks to give more generous, spirited interpretation to constitutional texts.”

He added that the two countries were united in a quest to discover what kind of civilisation they wanted to be and create and the question of who and what the people of any country wanted to be was an important part of constitution-making.

“That is a quest that is common to both our countries. What kinds of civilisation do we want to embody?”

Cameron said, in general, the power that laws regulate had been exercised for the benefit and protection of a small, privileged elite. But it was important to remember that kind of privilege is not a necessary feature of law.

“Law, as a system, must be general, prospective, comprehensible, comprehensive and predictable.

“This means that in its very nature law provides inherent nuances and contradictions in the hands of innovative lawyers and willing, innovative judges. These enable subversion of privilege of power.”

He said the law could provide a social mechanism that can liberate and enhance the dignity and power of the dispossessed and the marginalised and could help realise a just society.

He said since the end of apartheid, the South African constitution has included human, economic, environmental, and even sexual and gender rights, all in the name of equality and human dignity, to curb the dominant elite’s power, to provide a hedge for minorities against the power and the whims of the majority and ensure those who wield power were subject to the law.

He admitted the law could be distorted by lawyers and even ignored but, in general, the Constitution acted as a buffer and fought oppression. But, he stressed, nothing was immediate. It will take time and practice.

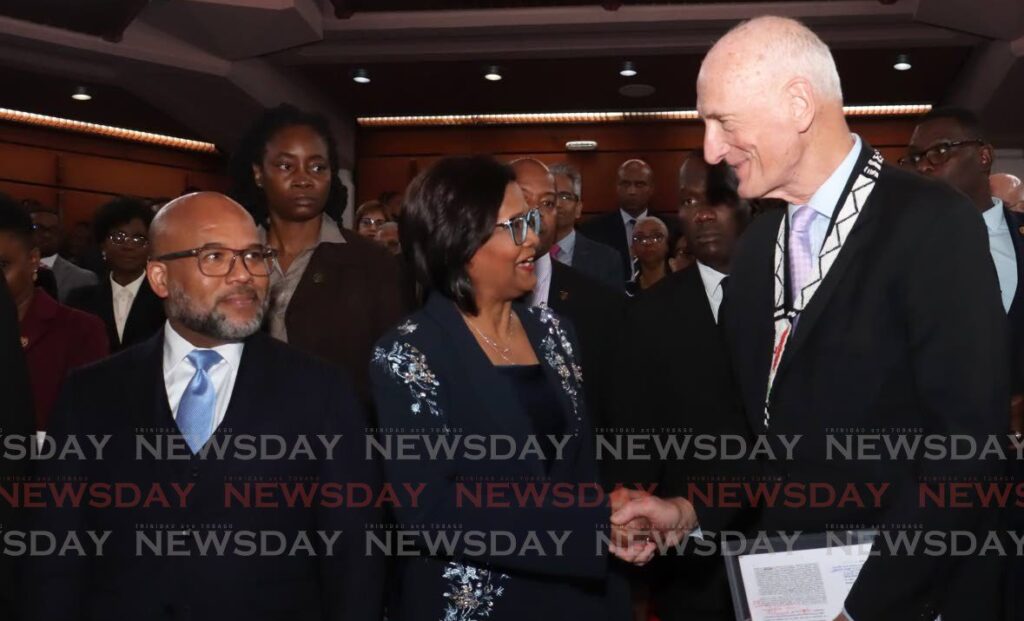

Also in attendance were President Christine Kangaloo; Attorney General Reginald Armour, SC; Speaker Bridgid Annisette-George; Chief Secretary of the Tobago House of Assembly Farley Augustine; British High Commissioner Harriet Cross' and Chief of the Santa Rosa First Peoples Community Ricardo Bharath Hernandez.

Comments

"South African jurist advises: ‘Make laws to tackle societal ills’"