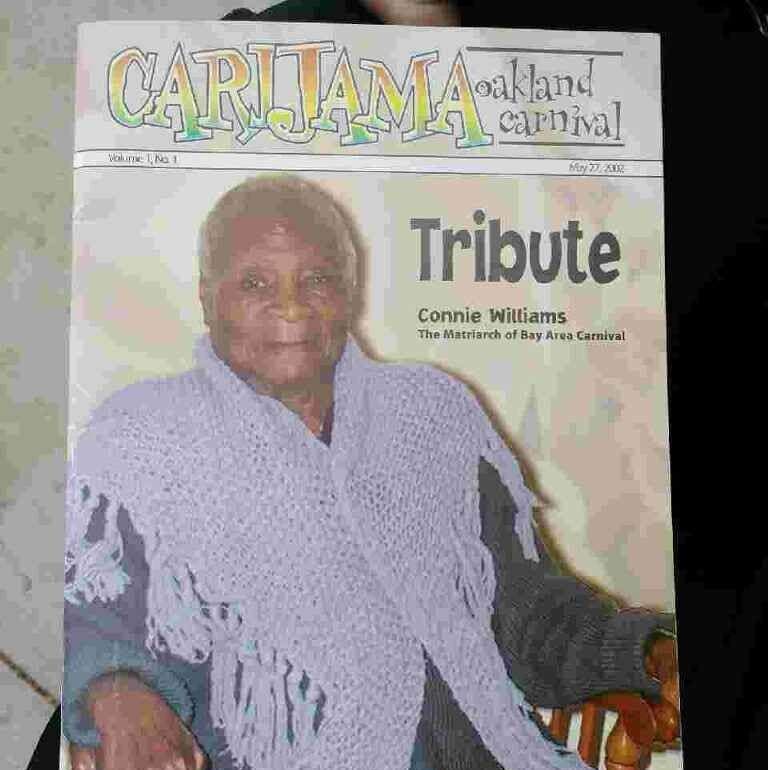

Connie Williams: Pioneer of calypso, Trini cuisine in the US

RAY FUNK

Connie Williams was a key figure in TT culture in the US in the 20th century, yet little remembered today.

She was known for running the Calypso Restaurant in New York City in the 1940s and 1950s, and later Connie’s Restaurant in San Francisco in the 1960s and 1970s.

She is perhaps best known for hiring a teenage James Baldwin for her New York restaurant and inspiring him and others.

Throughout her career, she was a strong supporter of the arts in general and TT culture in particular: she backed calypso, pan and mas through innumerable concerts and dances on both coasts, and was perhaps the first chef to popularise TT cuisine.

Little is known about Williams’s early life except for what is preserved in a 1939 declaration of intent to be a permanent US resident. Williams was born in Port of Spain in 1905 and migrated to the US in 1924. She lived in Harlem, and initially worked as a nurse or domestic servant.

She opened her calypso restaurant in 1942 in the basement of 51 McDougal Street, just a few blocks from Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village.

Almost from the beginning, it became a popular spot. A recent New York Times article noted: “In 1943, (painter Beauford) Delaney introduced a 19-year-old James Baldwin to Connie Williams, a Trinidadian restaurateur who had just opened Calypso Restaurant – whose patrons would include Tennessee Williams and entertainers such as Eartha Kitt and Paul Robeson – in a basement space on McDougal Street.

“Hired as a waiter at Calypso, which had live music and dancing, Baldwin mixed with the bohemian clientele. Among the habitues who befriended the erudite young server was the writer Henry Miller. But the occasional customer with whom he may have developed the most enduring friendship was Marlon Brando.”

A Wikipedia piece on her points to a wide range of supporters: “Other artists, performers, and intellectuals who frequented the Calypso included Henry Miller, CLR James, Tennessee Williams, Eartha Kitt, Paul Robeson, Richard Wright (author), Grace Lee Boggs, and Paul Robeson.”

Lee Boggs, social activist and author, noted in her autobiography that Richard Wright also frequented the restaurant. Boggs herself went to stay with Williams in San Francisco. Baldwin’s friend Stan Weir wrote recently: “The Calypso was catching on fast in a unique segment of the public, especially among radical intellectuals. CLR James, for example, sometimes brought Pan Africanists; Buford Delaney attracted the Henry Miller crowd; and then there were the dancers, musicians, actors and singers from the equivalent of what are now the off off-Broadway shows – many were West Indians carrying developed political attitudes.”

Baldwin himself wrote about Williams, “Because of (Beauford Delaney and) Connie Williams, a beautiful black lady from Trinidad who ran the restaurant in which I was a waiter…I was never entirely at the mercy of an environment at once hostile and seductive.”

Dancer Pearl Primus, who was born in Laventille but raised in New York, met Baldwin at the restaurant. When Primus took a group of ten dancers to Trinidad in 1952, Williams raised funding for the trip.

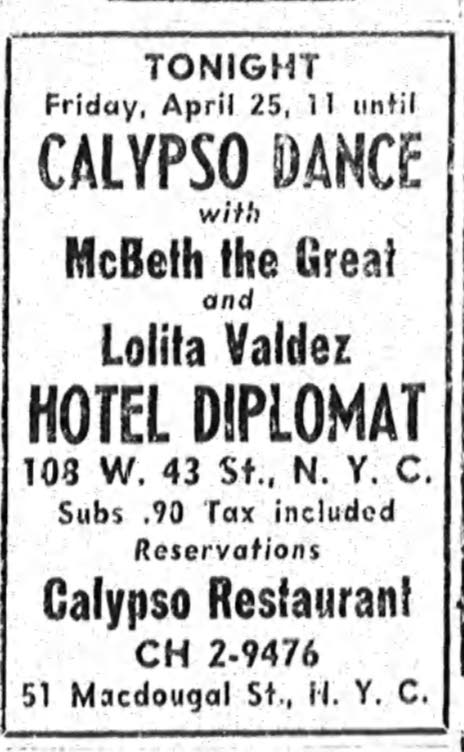

Williams became a key force in the TT community in New York. In 1945, she started to sponsor Carnival dances in Manhattan, held over several years. The 1950 dance featured “the exciting rhythms of Macbeth the Great and a sensational floor show.” That year, she also sponsored a moonlight boat excursion, again with both Macbeth and a steelband performing. Over 3,000 people attended. She also sponsored a two-week Carnival trip to Trinidad in 1951.

In 1952, she was connected to the Calypso Players, who were planning to launch a calypso musical by an early TT playwright, Kate Bourne. It is unclear if it was ever produced.

For Easter that year, she held an event at the restaurant with Lord Invader and other calypso artists from Trinidad. For her Halloween costume ball that year she had not only Macbeth but also the steelband of Rudy King and a dance group with Asadata Dafora from Sierra Leone.

In a 1979 interview, Williams explained her popularity: “All the people I met…were bohemians…and I guess I was too. That’s why I’ve never had any money.

“To look at me now, you’d think I was born fat but I wasn’t. I used to pose for these young artists. Fifty cents an hour. Then I’d take the money and buy food and cook it for them. That would happen two, three times a week.”

By the fall of 1946, she had been invited to be a speaker at a career and small business forum at a library in Harlem in a programme on successful women. She was to “describe her success in transforming a speciality – her flair for spare ribs – into a profitable business.”

But the restaurant seems to have closed in the mid-1950s, which led to a whole new phase.

Williams moved to California in 1959 at a friend’s suggestion. Initially she ran a restaurant called Caribbean Gourmet in downtown Santa Rosa, but it was short-lived.

In 1962, she opened Connie’s Restaurant at 1466 Haight Street, half a block from the legendary intersection of Haight and Ashbury. RB Read noted in The San Francisco Underground Gourmet: “The food is darkly rich, spiced by a master hand. Connie is famed for her curries, for her gumbo, and for her chicken dishes. The only bread served is her homemade coconut loaves.”

In 1965, the San Francisco Examiner announced Baldwin would visit his old friend.

“Would you like to know what Connie Williams of Connie’s West Indian Restaurant will cook for James Baldwin when he comes here in May? Baldwin practically lived at Connie’s New York restaurant years ago when he was a struggling young writer. She’ll serve him his favorite, black-eyed peas and rice, curried eggplant and beef and chicken Trinidad.”

But having a restaurant in the Haight during the age of Aquarius proved a major challenge. Read wrote: “The general public, it appears, is so bugged by the hippy scene on Haight that nobody but her regulars and the most daring newcomers will venture near the place.”

She relocated to 1909 Fillmore Street in 1968. A decade later, a restaurant reviewer for the Examiner gave it high praise in a review entitled West Indies Bounty: “There is no dining experience in San Francisco more special, more deeply rewarding than Connie Williams’ West Indian restaurant on upper Fillmore.

“Nor is there a better bargain. From soup to fresh-baked cobbler, the aromatic foods of Trinidad served here are all homemade, by Connie herself and the complete spread – with soup, salad, entree with fresh vegetable, homemade bread and dessert – is priced from $4.85 to $6 tops.”

In 1966, she brought up her nephew Reginald Niles from Trinidad, and, over the next few years, his two sisters, to help in the restaurant and give them the opportunity of a new life in the US. He recalled the whole time, she remained the cook.

“When I got there, the restaurant wasn’t booming. Then suddenly it started growing wildly, every seat was filled, people were standing in line outside to get in. We had celebrities come by. One was Leontine Price, the opera singer. She came by a couple times, and Robert Vaughan from The Man from U.N.C.L.E.”

Niles especially remembers her curried chicken, jambalaya and sweetbread. He worked at the restaurant during the week manning the cash register while studying civil engineering. On the weekends, he went with her to shop at the local farmer’s market and was a waiter. He recalled the restaurant was closed on Mondays and normally stayed open until 11 pm.

A 1974 restaurant guide noted: “No attempt has been made to hide the kitchen from the customers’ view or mask the smell of food cooking. While the aromas are cranking up your appetite you can glance back and see Connie in a calico dress and bandana preparing your meal.”

As in New York, a restaurant was never enough. Williams started dances in the vein of what she had done in New York, and was very involved in the formation of the San Francisco Carnival in the 1970s. Pannist Harry Best recalled she “had a deft understanding of the pieces of the political chessboard.” In the complex world of San Francisco politics, she was vital in guiding carnival organisations in getting the San Francisco Carnival going.

Her reach went beyond the Caribbean community. In the summer of 1975, the San Francisco Black Teachers Caucus organised a fundraising tribute for Williams and her restaurant for all she had done for progressive causes in the Bay Area over the years.

“Connie’s Restaurant has been the site of fund-raisers and benefits for every struggle from the Vietnam War and political prisoners to defence of the Soledad Brothers, Angela Davis and the San Quentin Six.”

By 1979, Williams expressed exhaustion and appeared ready to close her restaurant.

“I’ve been in the restaurant business since 1942 and that’s an awfully long time.”

Exactly when she closed the restaurant is not clear.

In 1959, she self-published a small booklet, 12 Songs of Trinidad. Scholar John Cowley has noted it is the only source of certain important early calypsoes. She was said to be working on a book to be called Child of Calypso, about her “childhood on the island of Trinidad and her life as owner of a restaurant in Greenwich Village which was the headquarters of the calypso set in New York City.”

Sadly, it was never published. She died in 2002 at 97, after her amazing career supporting TT culture in the US.

Comments

"Connie Williams: Pioneer of calypso, Trini cuisine in the US"