How a mermaid changed Monique Roffey's life

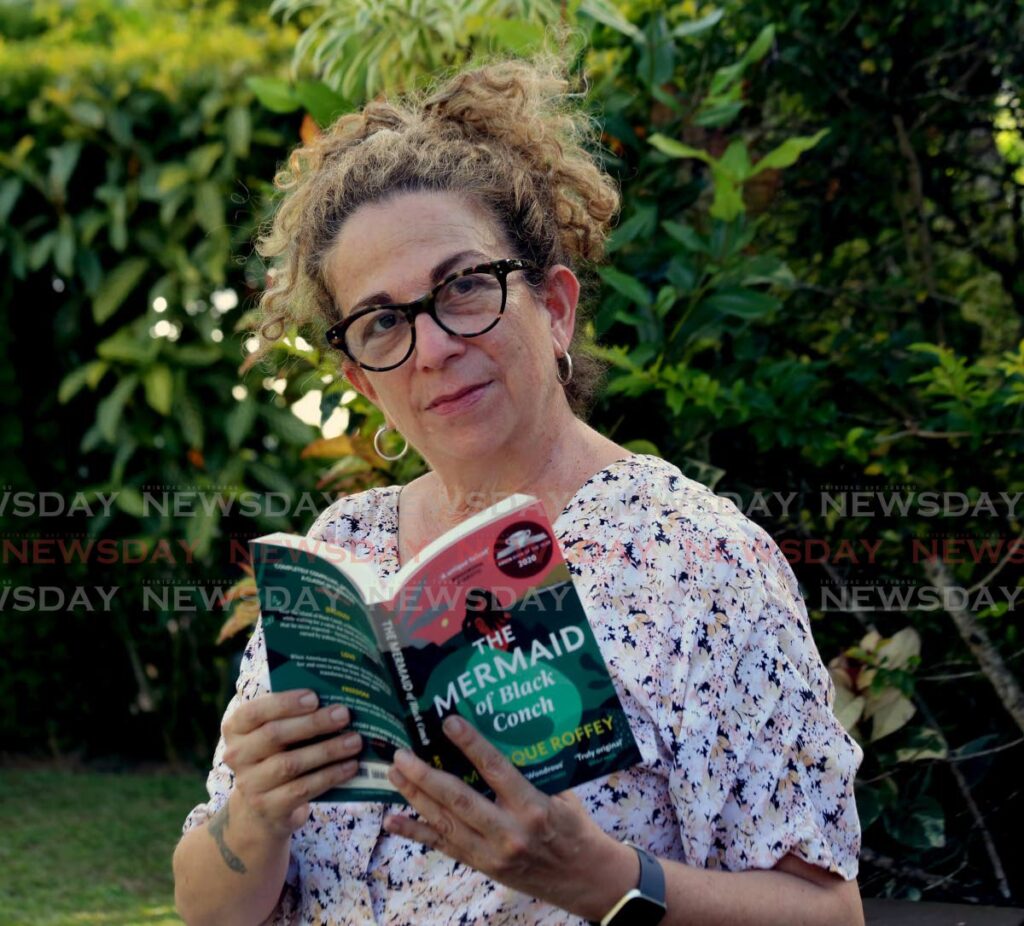

Most people can’t say that a mermaid changed their lives, but writer Monique Roffey certainly can.

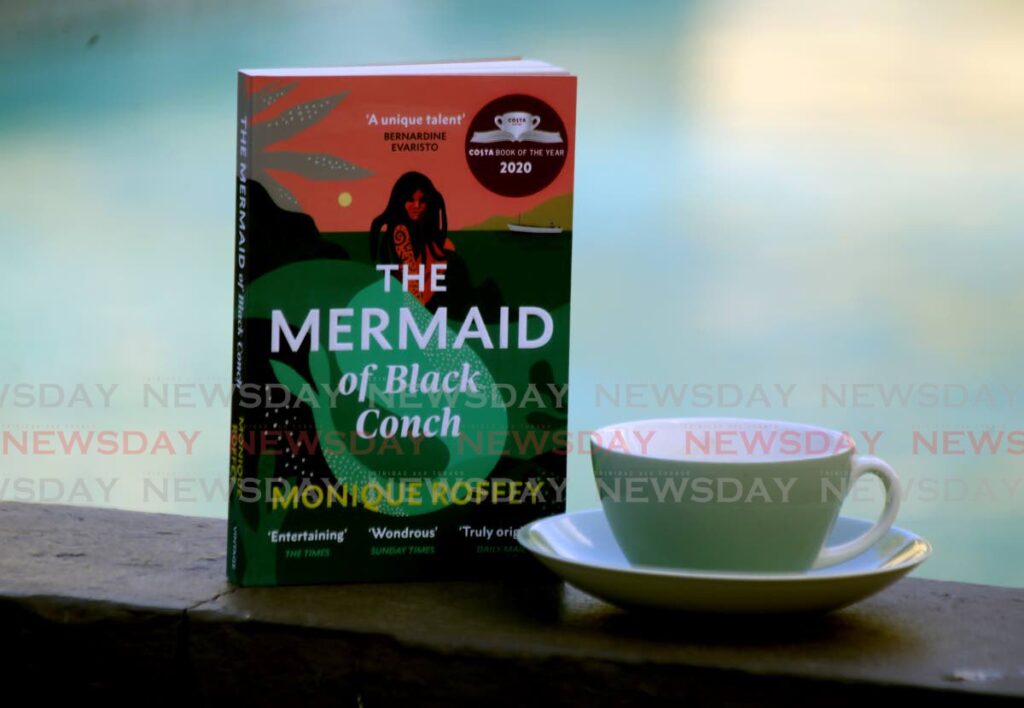

Released near the beginning of the pandemic, Roffey’s sixth novel, The Mermaid of Black Conch, came out of the blue to claim the Costa Book of the Year award for 2020.

Then, there was no catching the mermaid.

Suzannah Lipscomb, the historian and broadcaster who chaired the judges for the Costa prize, said Roffey’s novel was, “utterly original – unlike anything we’ve ever read – and feels like a classic in the making from a writer at the height of her powers.”

Roffey, 55, had been writing for 20 years before her mermaid captured international attention. She had first imagined the mermaid while staying in Charlotteville, Tobago in 2014. After seeing a marlin caught in a fishing competition and hanging above a jetty, Roffey dreamed of a mermaid being pulled from the sea.

That dream made this novel different from all of the rest.

“It is different to dream a story,” said Roffey. “If your novel is deeply rooted in the unconscious, it gets lodged there.”

Later, Roffey learned of the Taino legend of the alluring mermaid Aycayia with a sweet voice. The dream and the myth converged in the author’s imagination.

In 2016, Roffey began to write the mermaid’s story. Set in1976, in the tiny village of St Constance on the fictional island of Black Conch, the love story between a fisherman and a mermaid symbolises the region’s colonial history, touches on environmental issues, exposes prejudice, jealousy and misogyny yet the novel never got bogs down by its multi-layered, deep meaning.

When mainstream publishers turned down the mermaid, Roffey found her a home with the small independent Peepal Tree Press, which focuses on literature from the Caribbean.

That mermaid, conceived in a dream, would not be abandoned.

In 2019, Roffey turned to crowdfunding to raise money for the book’s publicity campaign. The mermaid took an unexpected turn. When it captured the Costa prize, it began to break through barriers. The mermaid's love story resonated with international readers.

“I think when you work with legend, you’re pricking that nerve of the collective unconscious,” said Roffey.

Still, Roffey wanted to transcend the realm of legends.

“Old stories are flawed – especially if they’re starring women. They’ll always be about female surrender or teaching the woman a lesson, or something to do with controlling women.”

Roffey had the power to change that narrative.

Her mermaid was "cursed and exiled and denied her erotic rite of passage in the old story. I got to change that and give her a love story. She beats the curse. I’m trying to say, ‘OK. Let’s bring her out of the sea again. Let’s give her what she’s been denied.’”

It’s easy to credit the novel’s success to its overlapping layers of legend and magical realism or its themes of power and independence, but Roffey claims, “I won the prize because of my cat, Fancy. She was a good luck charm, and there was a shift in consciousness because I converted to Buddhism. After this, things went well for me. I am not being flippant. I’m 56, something had to shift.”

Roffey has been studying Buddhism for four years.

“I am fully converted. I have chosen my own spiritual path as opposed to having my religion given to me. I tend to bring it up. People aren’t interested, and I think it is very fundamental to who I am.”

She calls the mermaid’s success “a miracle” and points out “people did not start reading the book until it had won the novel category in the Costa awards.

At the time she thought, “There are gods moving the furniture around up there.”

Roffey had been “relieved and pleased” when Peepal Tree agreed to publish the book initially rejected by mainstream publishers.

“It is a great publisher, but an independent publisher. I knew the book was confined to a small readership. I knew Peepal Tree is like the gold stamp of Caribbean literature. I felt happy to be in that kind of stable. Jeremy (Poynting, founder and manager of Peepal Tree Press) is extremely good at working with Caribbean literature. I thought if I’m not going to be picked up by a mainstream publisher, this is the next best thing.”

But the mermaid worked her magic.

When it was announced that the Mermaid of Black Conch had won the novel category, Roffey and her publisher felt the novel could sell 15,000 copies.

“And that would have been a success.”

But the mermaid kept crashing through literary barriers.

“It’s like a Cinderella story. It’s like you’re going to the ball,” said Roffey about the way the mermaid shot to fame.

“We have sold 100,000 copies, and it’s going to be repackaged and launched in the US,” said Roffey.

The Mermaid of Black Conch now has 13 translations, and she’s heading for a movie. Now, Roffey has to live with the success of the mermaid.

“You go forward as a writer over the years knowing success on this scale is not likely to happen, but you do it anyway, feeling the fear and pushing on. That’s true of how most writers operate. They want to write, come what may. I was completely flabbergasted for months by the book’s success,” said Roffey.

"I cried when I won the Costa prize."

Roffey thinks of her current success not as a reward for writing this one book.

“This is about sticking it out for 20 years. My backlist is being republished, and I have at least a good ten years ahead of me of writing.”

Financial success gives her the freedom to keep writing and elevates her to a new position of power.

“I can keep writing, and there is a gift of karma in there too. I get to recycle some of the magic and help other writers.”

She is currently judging the Orwell Prize for political fiction.

Some writers flinch at being categorised as a certain type of writer, but not Roffey. She describes her writing as “magical realist, intersectional feminist, bicultural and binational."

"I was born in a colonised space with European, colonial parents. I’m Buddhist. That shapes me. I wouldn’t necessarily put Caribbean writer up front, but I would use Caribbean as well to describe me. It’s just not the single name tag I would want to put on myself.”

In the canon of Caribbean literature, Roffey said she would place The Mermaid of Black Conch as “post modern in its composition and feminist. I’m using a Caribbean myth that isn’t an African myth, and why would I use an African myth? I’m not African.”

Instead, Roffey has shaped a legend that transcends any one culture.

“Mermaids are pan-global icons and outsiders. Every ocean has a mermaid; every culture has mermaid stories.”

Roffey enjoys readers’ reactions to her mermaid.

“It is amazing when people read you properly and have great questions. Lots of people have given me endings I didn’t think about. People have said, ‘Did you ever think about turning David into a mermaid so they can swim off together?’ A lot of people say it doesn’t have a happy ending, but she doesn’t have an unhappy ending. She gets her ritual of erotic love.”

In the end, Roffey’s mermaid challenges the dynamics of traditional male/female relationships.

“It’s a book about a woman who doesn’t know the rules of modern society so in the love story David has to catch himself. He can’t give chase. He can’t rule her in the modern way. He might scare her off. He realises he has to wait on her.”

Without any hesitation, Roffey identifies her favourite scene in the book.

“The scene I’m proudest of is when she goes to David sexually. Writing a scene where a woman has sexual desire for a man is hard to imagine. We are so conditioned by patriarchy, it’s hard to fathom what a virgin would do if she doesn’t know what is wrong and what is right.

"I wanted to give her power and grace. She just gets to be herself and step forward into her sexual desire. I feel proud of that scene. I just hope that is a good scene.”

Roffey is 55,000 words into a new novel which she says will “tackle the subject of femicide in Trinidad.”

Juggling publicity for a successful novel while writing a new novel can be daunting, but Roffey, who teaches creative writing classes says, “I’ve been very lucky. I had a sabbatical from my job to write. I was able to respond to all the press and publicity for the mermaid and still had times to write.”

In May, she returns for the first time in 18 months to work part-time teaching a memoir writing class. In September, she returns to teach full-time at Manchester Metropolitan University.

Last month, Roffey returned to Trinidad to visit her mother for the first time since the world turned topsy turvy through the pandemic. Here, she soaks in her Trini roots.

“Being A Trini is important to me. Don’t tell me I’m not a Trini – that would get on my nerves. I’m Trinidadian-born and split culturally between here and England. I feel comfortable in both places.”

Like the mermaid she created, Roffey’s world knows no boundaries.

Comments

"How a mermaid changed Monique Roffey’s life"