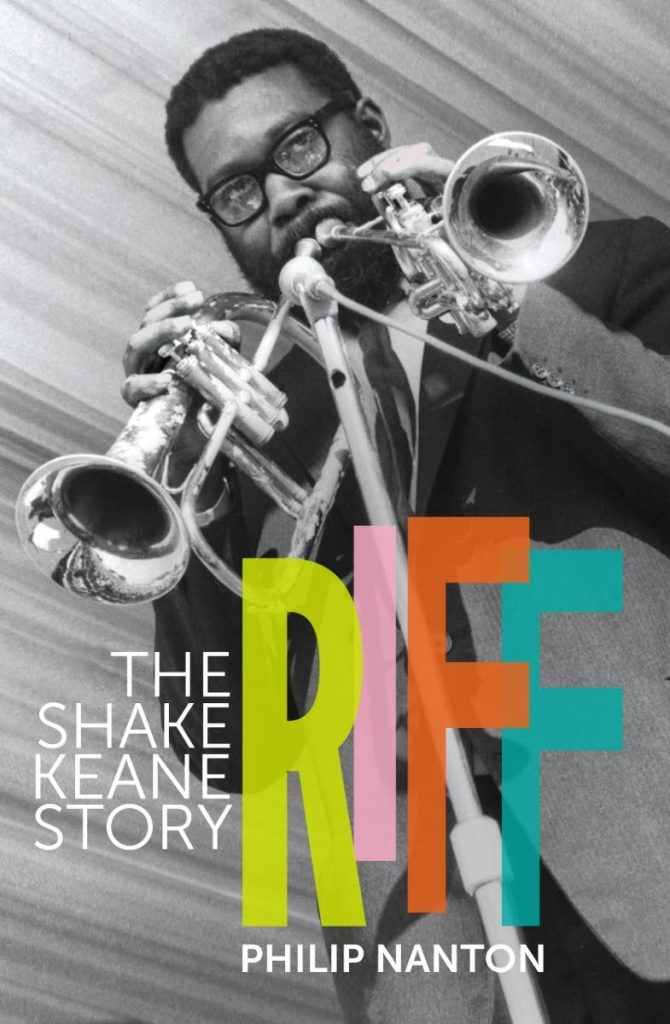

Shake Keane's bio a rich story of poetry and jazz

RIFF: The Shake Keane Story, a biography of the Vincentian musician and poet, was launched during a virtual event on January 28 (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ANehsC28xoI)

Its author, Philip Nanton, will appear at the Bocas LitFest on April 23 at 8 pm. St Lucian writer John Robert Lee, interviewed him.

What inspired you to write this biography of Shake Keane? Is it a first biography of Keane?

The short answer is that Shake’s life contained many elements of a good story: up from humble beginnings in St Vincent, international acclaim in the jazz world, especially in England and Europe of the 1960s; a triumphal return home that went sour because of political machinations, followed quickly by a struggle to survive his last years in New York.

It also helped that I had met him back in 1979 and got to know him to a limited extent.

Shake was an important influence on my writing, especially my Island Voices from St Christopher & the Barracudas. This collection of monologues and dialogues, first published as a CD in 2008 and in book form in 2014 (Papillote Press), is indebted to his brand of satirical humour.

Other elements of his story also appealed to me. He was a rare artist with highly-developed skills in both music and poetry.

His life story reflected also common Caribbean experiences, including migration and the return home with a sense of national duty,

Finally, there was the contradiction that people in St Vincent demonstrated over time – a mixture of pride in Shake’s achievements when abroad, alongside a disdain for his contribution when he returned to offer it to the island.

In many ways, then, there was a rich story waiting to be told, and no one else had come forward to tell it.

You mention three major influences on Shake’s life and work, which also played a part in the lives and work of his artistic contemporaries: the rise of nationalism in the Caribbean from the thirties; the experience of migration, eg Windrush; and the views of, and practice of “masculinity.” How were the issues of masculinity manifest in the music, poetry and life of Shake Keane?

Essentially, I understand masculinity as a form of learned behaviour.

Music and poetry I understand to be concerned primarily with emotions that a good artist can create and anyone can experience.

As such, it is hard to assign a gender to music and poetry, which deal with universal human emotions. All three involve performances, but performances of very different types.

Shake showed himself to be “one of the boys” in many ways. The music environment that he inhabited – the bands that he played in – for most of his life was predominantly a male one. His original instrument, the trumpet, was traditionally seen as a male instrument.

-

Similarly the touring with all-male bands, as well as being a regular at alcohol-fuelled late-night music dives in London’s Soho with their jam sessions all reflect conventional masculine behaviour.

Late in life, his nostalgic longing for friendship was reflected by his regular phone calls at any hour to male friends dotted around the world.

There were also less appealing features of this masculinity. He drank regularly and heavily when under pressure. He was an absent father to his three children, he exhibited a serial dependence on his three wives and, occasionally, he lashed out violently against those nearest to him, to the extent that I have come to understand that his second wife left him for that reason.

So it’s important to state plainly, also, that Shake was no saint.

How did the musicianship, and in particular his development with the Joe Harriot quintet of free-form jazz, shape the poetry? You suggest that “he often applies what could be called a jazz rule-breaking style to the composition of poetry.”

It’s true that Shake did claim that he saw his poetry and jazz as unrelated to one another.

I argue that cross-over elements from jazz to poetry can be detected in two ways, first by the different ways that he improvised on the page; and, second, through the ways that he exploited the notions of “play” and “playing.” His improvisations call-and-response poems, the formation of visual poems and the location of individual words, displayed almost like single notes.

Would you consider Shake a pioneer of Caribbean literature?

If by pioneer you mean someone who strides out on his own to make a mark in some field, then I’d say yes.

I know of no one else from the English-speaking Caribbean who has combined poetry and jazz to reach the level that Shake achieved.

Certainly, there are other Caribbean artists who also mastered a number of genres. I’m thinking of Derek Walcott with poetry, drama and his watercolour painting; there is also the late Jacques Coursil, the French/Martinique trumpeter – a jazz/ classical musician and professor of linguistics whose work I discovered recently.

The main characteristics that Shake valued as central to Caribbean poetry were “joy” and “exuberance.” These are probably not pioneer features of his poetry, but both overflow in his work. I would argue that we need them always but, especially in these covid times, we need them more than ever.

You say that Shake Keane could be fairly described as “a minor poet.” Where in his poetry do you think he offers still-undiscovered glimpses of making major contributions to the development of West Indian poetry?

In essence much of his work disrupts the clear lines of demarcation between styles and genres that critics often require. Located at the crossroads between jazz and poetry, Shake’s most significant achievement was ultimately a blurring of the boundaries between these two art forms. The collection One A Week With Water: Rhymes and Notes is the most compact example of this process.

I used the term “minor” to describe Shake’s poetry because of his limited output, impact and his style as an artist.

Then there is the issue of reception of his work. He deploys overt as well as underlying humour in much of his work. I suspect that this combination has resulted in critics not taking his work seriously. If critics bypass the work. then it simply falls out of the frame.

Shake was not the sort of person to beat a drum to announce himself as an artist, though he was a powerful and gregarious presence when around people. In his approach to jazz and poetry he showed a style that was easy-going yet humble.

Did Shake write enough religious poetry to make him a significant voice in the fairly rare literature of the Caribbean that treats of the theme of Caribbean spirituality and religion?

Probably not. But the two articles about early religious poetry of the Caribbean that he wrote for Bim in 1952 indicate a sense of spirituality and a certain openness to spirituality that I would argue he never lost, despite a life that at times contained considerable turmoil.

His later Volcano Suite are five contemplations on what he calls a “Natural Presence” co-ordinated with our presence on the planet. There appears to be in some of his writing, then, an exploration of nature as a way to God.

But these scattered poems are not a sufficient body of work to rank alongside committed and profound religious poetry like that of Mervyn Morris, John Figueroa and yourself.

Finally, how would you assess the contributions of Shake Keane to Caribbean arts and literature? Does he need to be rediscovered, both his music and poetry? How do you think this new biography can help?

I hope that I have made a case for Shake’s work to be rediscovered. The originality of his jazz/poetry association, the music itself and his essentially celebratory, exuberant poetry remains a delight to be discovered for those who will come across it for the first time.

If my biography helps to steer more people in Shake’s direction I will be pleased.

RIFF: The Shake Keane Story is published by Papillote Press (London; Trafalgar, Dominica)

Comments

"Shake Keane’s bio a rich story of poetry and jazz"