Accelerating towards a Blue Economy

Farahnaz N Solomon (PhD)

Research Officer,

Institute of Marine Affairs

“There are more opportunities in the ocean than we can fathom.”

Oceans cover 72 per cent of the Earth’s surface. They support life by generating oxygen, absorbing carbon dioxide, recycling nutrients and regulating global climate and temperature. Oceans are important for fisheries, transport, and tourism – all traditional sectors of the Blue Economy. Highlighted at the 2012 Rio +20 Conference, the Blue Economy can be defined as 'the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods and jobs, while preserving the health of the marine and coastal environment.

Using the sea for economic gain is not a novel idea – in 2010, the global ocean economy was conservatively valued at US$1.5 trillion with a projected increase to over US$3 trillion by 2030. Regionally, the gross revenue generated by the ocean economy in the Caribbean Sea in 2012 was US $407 billion with US$53 billion generated by Island States and Territories. Unfortunately, in pursuit of these economic gains, the health and productivity of the ocean’s natural capital – marine living and non-living resources, and marine ecosystems and the good and services they provide – has been degraded. The Caribbean Sea’s natural capital is being degraded by overfishing, coastal development, pollution (land-based and marine), the introduction of invasive species and habitat degradation. Climate change has worsened the impact, and overall, the benefits (ie food, employment, recreation) generated by the region’s ocean economy are being threatened.

To counteract this business-as-usual scenario and the loss of benefits from the ocean, the Blue Economy calls for a change in the way we use our ocean resources by placing greater emphasis on the environment, and in protecting the oceans “natural capital” to secure a sustainable flow of benefits. Similar to the Green Economy, the Blue Economy emphasises social outcomes – improved human well-being, improved livelihoods and social inclusion and equity.

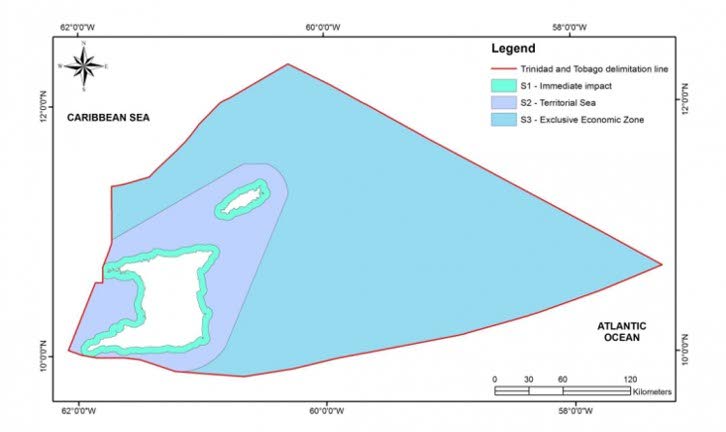

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in the Caribbean face several inherent challenges in pursuing sustainable development. These include small populations, a limited resource base, rising pressures for economic development and high vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change impact. In light of these challenges, the Blue Economy is a particularly attractive model for Caribbean SIDS. Given our extensive Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), Grenada’s EEZ is 75 times larger than its land area and TT’s sea to land area is about 15:1, the resource base of the islands is predominantly marine. Maximising economic and social benefits from this large marine resource base can help SIDS achieve economic diversification, poverty reduction, food security, climate change mitigation, ocean conservation and energy security.

In the Caribbean, there is potential for growth and innovation in traditional Blue Economy sectors such as fisheries, marine transport and marine-based tourism (coastal activities, yachting and cruise ships). There are also opportunities for expanding into new high value, emerging sectors such as sustainable aquaculture, marine renewable energy, marine biotechnology, and deep seabed mining. Despite this potential, most Caribbean islands have been slow in transitioning to the Blue Economy and in realising its full benefits. A notable exception is Grenada – one of the world’s first countries to develop a “blue growth vision.” Grenada’s national “masterplan” for blue growth identifies opportunities in fisheries and aquaculture, blue biotechnology, renewable energy and research and innovation.

Moving from a conventional resource economy in the ocean to a Blue Economy is no easy task. A key step is formal recognition of the Blue Economy as an important economic driver, allowing for mainstreaming into national and regional development plans and inclusion in national accounting systems. Also important is an enabling environment in the form of appropriate policies, legislation, infrastructure, and finances. Developing the Blue Economy requires new skill and human resources, for both current and emerging sectors. In keeping with Blue Economy principles there needs to be efforts to improve the employability and promote employment of vulnerable groups such a fishers, coastal communities and women. Innovative financing mechanisms such as blue bonds, insurance and debt-for-adaptation swaps are needed as blue economy investments can be costly.

Currently, there are several initiatives at the national and regional level that can assist the Caribbean in transitioning to the Blue Economy. A 10-year Strategic Action Programme (SAP) for the sustainable management of shared living marine resources in the wider Caribbean is being implemented under the Caribbean Large Marine Ecosystem Project (CLME+). This SAP addresses unsustainable fisheries, habitat degradation and pollution – the three main factors affecting the provisioning of goods and services from marine ecosystems. Also, under CLME+ and in accordance with the SAP, a regional policy co-ordination mechanism to facilitate integrated and interactive ocean governance is being developed. This will address “weakness of governance” – identified as the overreaching root cause of these three main problems.

At the country level, many islands are moving towards more integrated approaches to manage their coastal and marine environment, namely Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) and Marine Spatial Planning (MSP). Traditionally, the development of ocean-based industries has used a very sectoral approach focusing on economic gains. In order to achieve the principles of the Blue Economy, an integrated ecosystem-based approach is needed. ICZM and MSP both seek to co-ordinate and balance the needs of several types of activity within the same area. They are both characterised by an ecosystem-based approach that balances social, economic and environmental objectives, adaptive management, stakeholder engagement and cross sectoral integration.

Caricom has been actively participating in the development of a new international agreement for the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (ABNJ). Two-thirds of the world’s ocean occur in ABNJ – what we call the “high seas” and where no single state has authority. Major concerns for the region include the equitable sharing of benefits from emerging Blue Economy sectors in these areas like deep-sea mining and marine genetic resources, and the protection of this area from environmental harm from emerging and existing activities such as fishing and shipping.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development also supports the Blue Economy approach particularly through Goal 14 – “Life Below Water” which sets targets to reduce marine pollution, protect coastal and marine ecosystems, end over-fishing and IUU fishing and increase the benefits to SIDS from the sustainable use of their marine resources.

Despite these initiatives there needs to be greater focus and intensity with Blue Economy approaches becoming more pervasive. Moving forward there is an additional challenge as the covid19 pandemic has affected Blue Economy sectors such a coastal and maritime tourism, fisheries and sea food production and maritime transport. While the extent of the impact is still to be determined, the Caribbean’s reliance on its ocean for recovery and to build more resilient economies to secure the well-being of its people has become more obvious and urgent. Ironically, covid19 might have provided the added impetus needed to advance the region’s Blue Economy.

REFERENCES

1 World Bank, 2017 . What is the Blue Economy? Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2017/06/06/blue-economy

2OECD, 2016. The Ocean Economy in 2030 Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/the-ocean-economy-in- 030_9789264251724-en

3Patil et al., 2016. Toward A Blue Economy: A Promise for Sustainable Growth in the Caribbean; An Overview. The World Bank, Washington D.C Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/25061/Demystifying0t0the0Caribbean0Region.pdf?sequence=4

4UNDP, 2013. The Strategic Action Programme for the Sustainable Management of the Shared Living Marine Resources of the Caribbean and North Brazil Shelf Large Marine Ecosystems (CLME+ SAP) Available at: https://www.clmeproject.org/sap-overview/

5 CDB, 2018. Financing the Blue Economy. Available at: https://www.caribank.org/sites/default/files/publication-resources/Financing%20the%20Blue%20Economy-%20A%20Caribbean%20development%20opportunity.pdf

6UN Environment (2018). Conceptual guidelines for the application of Marine Spatial Planning and Integrated Coastal Zone Management approaches to support the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal Targets 14.1 and 14.2. Available Online: https://www.unep-wcmc.org/system/dataset_file_fields/files/000/000/548/original/Final_ConceptualGuidelines_240918.pdf?1538124788

7 UNCTAD, 2020. The Covid-19 Pandemic and the Blue Economy: New Challenges and Prospects for Recovery and Resilience https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/ditctedinf2020d2_en.pdf

Photo 1: Map showing the extent of Trinidad and Tobago’s marine area. – SIDS have a large marine resource base Photo Credit: http://www.iczm.gov.tt/2019/05/08/what-is-a-coastal-zone

Photo 2: Fish Landing Site - Fisheries is a traditional Blue Economy sector, contributing to livelihoods, food security and well-being in coastal communities

Comments

"Accelerating towards a Blue Economy"