Poet Roger Robinson: The fire next time

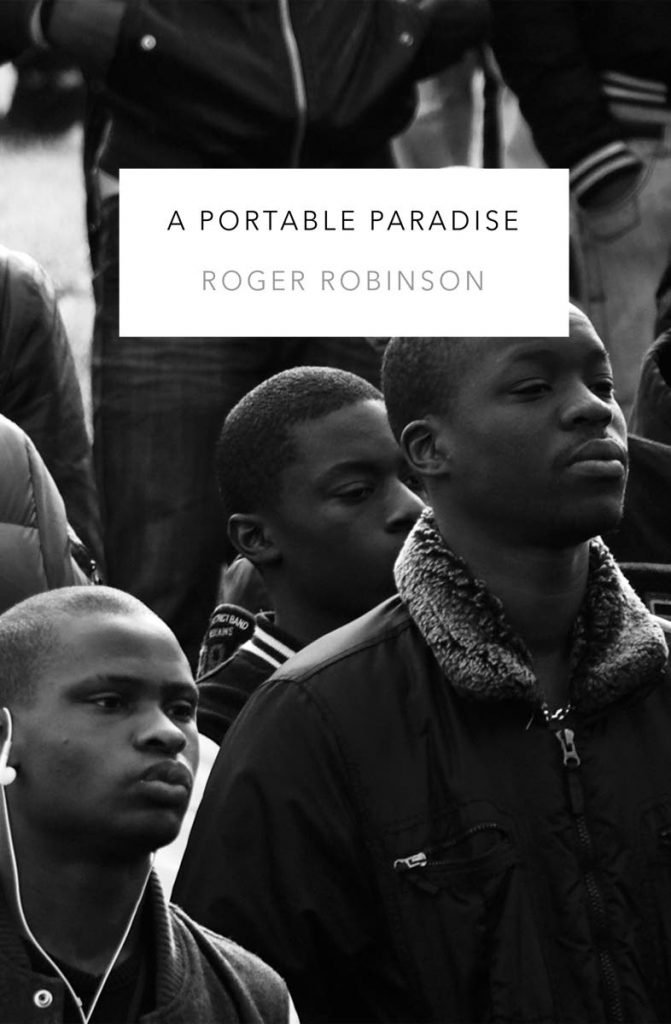

SATAN has some of the best lines in Paradise Lost. Milton gives us, “The mind is its own place, and in itself / Can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven.” This sense of the world as idea, of reality shaped by perception, streams through Roger Robinson’s powerful book of poems A Portable Paradise, which continues to earn honours for its author.

In January, Robinson’s book was awarded the TS Eliot Prize, one of the most coveted in the poetry world. Earlier this month, it also won the Royal Society of Literature’s Ondaatje Prize. It is only the second book of poems ever to win the award, which is named after the acclaimed novelist and awarded for a work that best evokes “the spirit of a place.” The accolades are set to continue. A Portable Paradise was last week shortlisted for the inaugural Derek Walcott Prize.

Yet, even without all these laurels, this would be a book worthy of our attention.

Robinson has Trinidadian lineage and has lived here. However, he was born in England. And while, in typical Trini fashion, he straddles worlds, he today identifies as British. He’s lived there more than anywhere else. And he first became a father there.

“I got to the point where I felt like I didn’t have the immigrant mind anymore, where I was not feeling like I am going home to Trinidad,” Robinson told BBC Radio 4 a few days ago. “I live in England, I’m black British now. I wanted to take the paradise I had in Trinidad and see if I could build it here.”

This idea of the reconstitution of British identity, of admitting the margins into the centre, of remembering but not being held back by history, of reversing erasures, and of defiantly asserting a claim to an identity long anxious of black and brown bodies is the powerful animus behind his book.

In many respects, A Portable Paradise is the culmination of a project of social excavation that begins with Robinson’s first poetry publication, 2004’s Suitcase. That book’s epigraph, from Raymond Carver, hints at the poet’s desire to tell stories people relate to. (Robinson’s first-ever book, published in 2002, was a hilarious short-story collection, Adventures in 3D, in which the ordinary becomes extraordinary.) The 2004 book’s title poem, Suitcase, opens ominously: “My mother tells me that for years/she has kept a packed suitcase/in her car trunk, just in case”.

Why would black British people need to do such a thing? In book after book, the poet answers.

Embers burn in Suckle, from 2009, in which Robinson delves further into family life, whether set in Trinidad or Britain. The personal is yet to boil over into the streets, though political implications are evident, such as in Emperors, where a seemingly marginal member of a dance crew is venerated: “I did the practical things, the support:/Someone had to carry the linoleum.”

Then on August 4, 2011, a police officer shot and killed 29-year-old Mark Duggan in London. The official account given was that Duggan, of mixed Irish and African-Caribbean descent, had fired a gun. This was untrue. There were riots for a week. Such was the unease, even the TT High Commission closed.

Robinson’s response was The Butterfly Hotel, published by Peepal Tree Press in 2013. Its opening suite contains poems such as Brixton Revo 2011 with its “trainer shops lit by flares of fire/As thick black smoke billows.” There is experimentation with form (the poet explores haiku, prose poetry, the litany). Personal narratives are subsumed within the conceptual project: threads and motifs are carefully interlaced. These flames would spread to the next, bolder book.

Much has been made of Robinson’s timely and moving poems in praise of medical workers, Grace and On Nurses, which appear at the end of A Portable Paradise. But the 2019 book’s most stunning poems are the ones right at the start. They deal with the tragedy of the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire that saw 72 people killed in the worst UK residential fire since World War II. The victims lived in a tower block very much like one Robinson had lived in (he recalls it in Suitcase). Class and race were perceived to have played roles in regulatory lapses.

The opening poem, Haibun for the Lookers, addresses those who witnessed the tower burning. A haibun is a Japanese form, an amalgam of prose and haiku. The device generates a heft that feels appropriate given the subject matter, which is a tragedy that itself stretches beyond the page. Dylan Thomas’s A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London, and Christopher Logue’s Come to the Edge are the opening poem’s spiritual twins.

There follows a movement of poems which each present a different perspective on, a different moment of the tragedy – as though the book is trying, repeatedly, to process a trauma. One account, Dolls, imagines an alternative reality in which the tragedy did not happen. Even when the poet moves beyond Grenfell, the ash settles everywhere. In It Soon Came, people sense something in the air, “then came the faint smell of smoke” which is polyvalent: it could be Grenfell or it could be riots.

When Robinson tackles the recent Windrush scandal, which has seen Caribbean descendants have legal entitlements retroactively reversed, he begins the poem: “They came down from the ship.” The suggestion is of the menial status given to black and brown people of the former colonies. But the phrase “they came down” also echoes the harrowing spectacle of bodies falling from a burning tower.

In a series of monologues called Citizen (which bring to mind Claudia Rankine’s recent book of the same name) Robinson sets out how all of these scandals have come, “after slavery, colonialism, two world wars.” But while there is a sense of activism – or what the poet often calls “creative citizenship” – these pieces are not didactic.

Nor are they merely “angry,” as some metropolitan critics have predictably claimed. Bristling with a sense of injustice and the barbarous machinations of history, they are nonetheless sophisticated enough to accommodate a range of readings. For example, as is the case in the earlier work, race could easily be taken as a metaphor for queerness or other forms of exile.

And the book is sublimely artful. As though ignited by a world of possibilities, Robinson pursues the haibun, the limerick, the prose poem, the palinode, ekphrastic poems, septets, short poems, sprawling poems.

Whereas in the earlier books there is a sepia tone, a kind of nostalgia for days of innocence, an obsession with mother figures, women and family life, here everything the poet touches turns to ash. The world has been torn asunder. It is his saddest creation, but his most powerful to date.

Robinson is often described as a “dub poet.” There’s nothing wrong with dub poetry. And he has released dub albums. But a casual online search quickly reveals the sheer range of his performative nouns.

Similarly, A Portable Paradise betrays an artist with a wide, commanding sensibility, willing to absorb the full complexity of history and experience. Whatever the jaded critics say, it is real life that has provided everything the poet used to write this shapely and accomplished book. It all amounts to a Gothic vision of empire, made all the more terrifying because it is real.

Instead of paradise, witness hell.

Link to BBC Radio 4 Today programme, with Roger Robinson at 1:41:50, https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000hvkk

Comments

"Poet Roger Robinson: The fire next time"