Soothing your stress

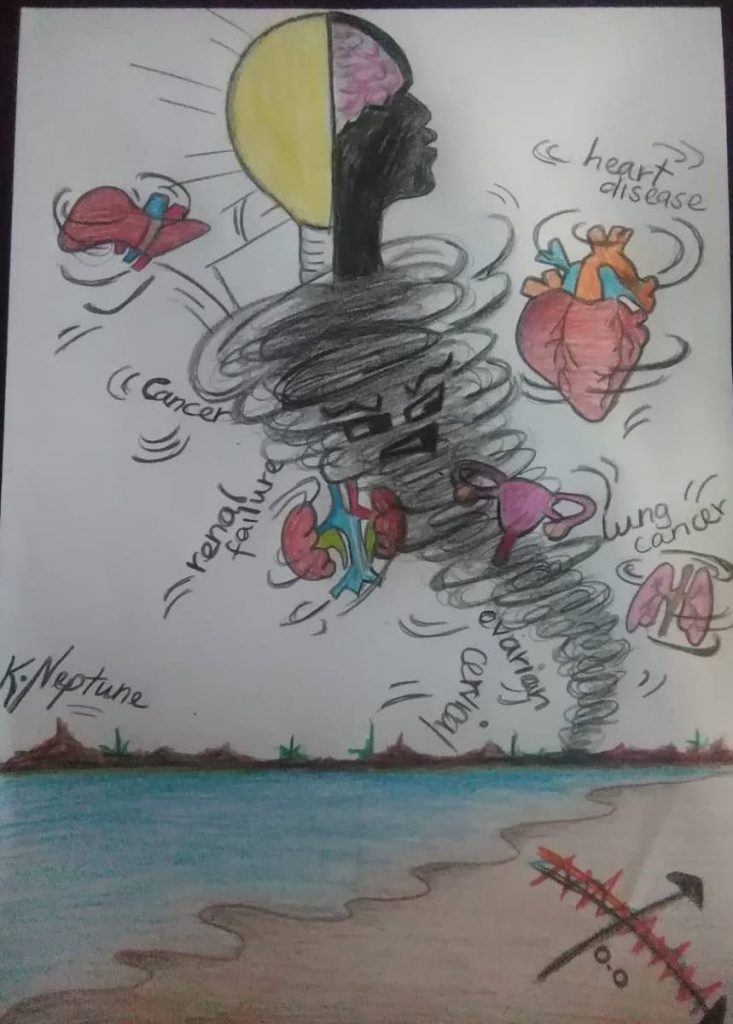

In part two of the Science of Stress, Newsday solicited artwork from our reading community. Art has been shown to be a modality used to help people express themselves when they cannot find words to say how they feel and is an act of mindfulness that helps people stay in the moment, keeping away from wandering thoughts.

Back in the wild African savannahs 200,000 years ago, the sight of animal carcasses or dead bodies were signs that danger was near, and the fight, flight, or freeze stress response was triggered.

Now, in the 21st century where there’s a low level of physical threat, there could still be a plethora of stress triggers, especially for the chronically anxious. The cryptic but ominous, “I need to talk to you” message could trigger stress. The pings of social media notifications cause a visceral reaction. Dreading seeing someone could be stressful. Seeing dead bodies on the news where there is no direct physical threat to a person triggers a stress response.

On May 1, Newsday spoke to Kheston Walkins, owner of Allegory, a neuro-innovation company that uses neuroscience to teach people how to regulate their moods throughout the day.

The following is are some techniques he uses to teach people how to regulate their emotions and manage their stress response. Walkins advised these techniques are not an instant solution and continuous practice is needed.

Noticing the body is experiencing stress is the first step in mood management. The body shows physiological signs of stress. Becoming aware of the stress will allow people to manage their moods. Any change in a normal bodily function, either increasing it or decreasing it, may be a response to stress.

Eating too much, going to the bathroom frequently, constipation and shaky hands are all physiological signs of stress. Signs of stress may vary, but an increased breathing and heart rate is a universal sign of stress.

If a person slows down their breathing rate, then they can slow down their heart rate. Deep controlled breaths where the exhale is longer than the inhale, through the nose and out the mouth, are the easiest way to reduce the heart rate.

“I tell my clients four seconds in, five seconds out. There are lots of different techniques, but I like that one because it is simple.”

Mindfulness techniques such as meditation and visualisations can also help when a person is able to sit quietly and observe their thoughts.

Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh, in his book The Art of Communication, says every thought a person consumes is either nourishing or poisonous. Repetitive negative thoughts, particularly negative self-talk, have a destructive effect on the mind.

Closing the eyes is also another way someone can calm themselves when they are feeling stressed.

“When you lock off a sensory modality, you have less to process. Vision consumes the most energy for the brain. Processing images is the most energy-consuming.”

A person who has anxiety has a lot of running thoughts. These thoughts can turn to worry quickly, especially if they recall threats from the past. These thoughts consume a lot of energy, but there is no physiological release.

“Anxious people have problems with prioritising things, so at a point where they are trying to be anxious, everything is going to be important, and that’s a problem.”

Humans are designed to process only a little bit of information at once. The brain intentionally ignores or filters out information to function optimally.

This can be used to the anxious person’s advantage by disrupting the running thought. Walkins suggests using “interrupters” like reciting a poem or singing a song.

“Find something that you know, a song, put the song on, and sing. What you are doing is interrupting the process of running internal dialogue or subvocalisation. We are interrupting that.”

It is easier to process images in parallel than language in parallel. You can watch and listen to a movie at the same time, but it is difficult to talk to someone and listen to them at the same time. The mind must quickly switch between speaking and listening to process the information.

Engaging the sense will help to interrupt the running thoughts. Walkins suggests feeling the clothes on your skin.

“Focus on a part of the body, the shoulder for example, and try to feel the clothes on the shoulder. It’s like you’re doing a scan and you’re feeling the clothes on your skin. Or feel the fabric of the chair under the legs. This keeps the mind from wondering. Wandering thoughts cause anxiety.”

He suggested engaging the senses the brain is conveniently ignoring.

“The clothes on your skin – you weren’t feeling it until I brought it to your attention. You can only focus your attention on one thing at a time. This is taking advantage of this neurological quirk to keep your mind from wandering away from you.”

All the senses can be used to interrupt racing thoughts.

Scents can evoke positive or negative reactions. The words “cake” and “poop” can provoke the mind to recall the smell and assign positive or negative judgments to the word.

“Scents literally affect your brain activity. Music also has that effect. It ignores cognition and gets into the limbic system or the emotional centres.”

Using pleasant scents like lavender, chocolate or freshly baked bread can help soothe a person who is stressed out.

Walkins says people can emotionally time-travel to a happy place with music.

Ali as a way of expressing a range of emotions words could not. -

“You get to take happiness out of the past. Music is one of the few ways I could think of as humans that we can do that.”

Imagine the happiest moment in life. It could be school days, the fond memory of gaining independence for the first time. Whatever the pleasant moment was, find music from that time and listen. The music will take your mind to that happy place.

“Music can take us back into the past and we can extract happiness from there. That for me is amazing. It’s one of the things people use but they don’t realise that they do it. This is called contextual-dependent memory.”

Contextual-dependent memory is the ability to remember something that is congruent with the mental state a person is in. When sad, it is easier to remember sad things. Happiness can jog happy memories. It goes down to learning and memory.

In 1975, researchers Godden and Baddeley published a paper on their famous diving experiment with contextual-dependent memory. It was observed that divers were having difficulty recalling their underwater adventures while on land. They gave divers a list of words to memorise on land and a different list when submerged in water.

The list of words learnt while underwater were recalled better underwater and the words learnt on land were recalled better on land.

“They remembered the list when they were in the environment (where) they learned it. This shows some people just need to change their environment and that would have a big impact on their stress.”

Clearing your desk and not working in places where you rest can all have subliminal effects on your mood.

While it is the individual’s responsibility to manage their own mental health, Walkins said it is impossible to do so without learning how the body works.

“You will spend less money on psychotherapy – and therapy is really important – but you would spend less money by learning how you as a human react and deal with stress because you found your own way to deal with maintaining your mental wellness.”

Therapists, he said, operate as a consciousness outside of the body. Psychotherapists sit empathetically with a person to help them work through their issues and heal attachment wounds from childhood development, but they cannot regulate a person’s mood.

“We think out loud with them. They can’t make us feel good. We may feel good after we talk with them, but if we have not learned, then we would always end up feeling bad again.”

Psychology and neuroscience, he said, should work in tandem to help someone cope with stress, as the two tools cannot fix all mental health issues alone.

If a person fears death, neuroscience cannot help. Reframing, a psychological tool to help see a situation from a different perspective, can help you deal with death.

“If you are anxious and you get panic attacks, psychology does not have a strong effect as some of the neuroscience techniques you can learn. That’s why there has to be a synergy between the two. Especially dealing with something like stress.”

Stress engages both the physiology – the corporeal self – and the psychology, the way a person engages themselves in the world. Though much of the brain is a mystery, there are neuroscientific ways to help ease the mind.

“Neuroscience is so powerful. The mind is so powerful. It is one of the things that’s the most diverse, but so congruent between us as a species. We would be fools not to engage it.”

Comments

"Soothing your stress"