Celebrating Kamau Brathwaite, tributes to Caribbean literary giant

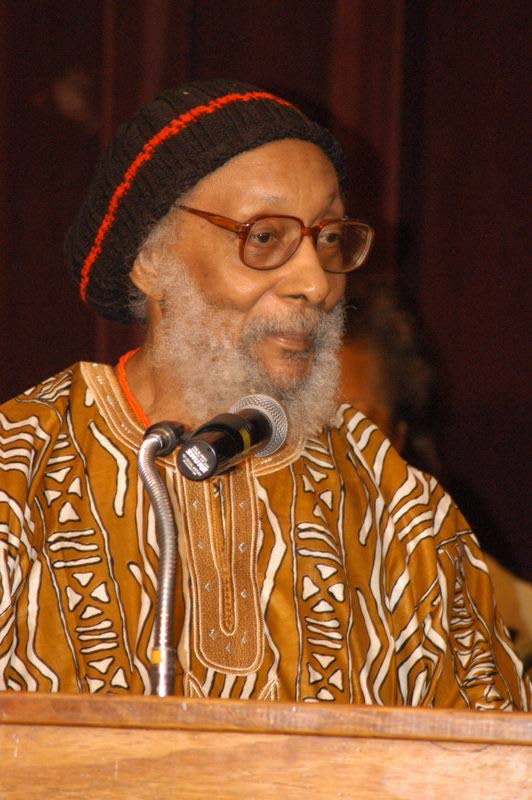

Barbadian poet and academic Edward Kamau Brathwaite signified poetry. He was a giant in Caribbean literature.

Prof Emeritus Kenneth Ramchand of the University of the West Indies, St Augustine said for decades, Brathwaite and Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott signified West Indian poetry.

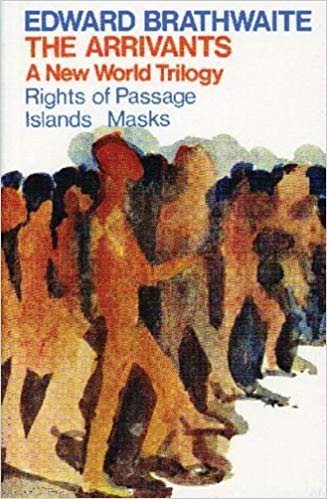

"Now both are gone. Kamau's first volume Rights of Passage, with which students were thrilled when I presented it to them in 1969 in the first full course on West Indian literature at The UWI, set the tone for his perennial concern: the rites of passage of the people who came to the Caribbean from many places usually in oppressive circumstances."

Brathwaite, 89, died on February 4. He was a writer, scholar and editor.

Ramchand said while he and Brathwaite had their literary disagreements, they worked closely at UWI, Mona, Jamaica to establish the magazine Savacou of which they were founding editors, a journal they linked with the Caribbean Artists Movement whose centre of gravity they hoped to shift from London to the West Indies.

Ramchand said they were united about the need for shaping UWI away from its identity (and some of its values) as a college of a British university. "Kamau was versatile and always interesting. He wrote a most important book about creolisation, discoursed extensively on 'nation language' which he demonstrated brilliantly in his poetry, and was the prime influence in the region's eventual discovery of its potent folk and oral traditions."

Ramchand said Brathwaite's work and his theories fed on the subterranean links between the Caribbean, Africa and the African diaspora, and it was especially sensitive to the music, rhythms and imagery of African American culture.

"We drifted apart, but I have never wavered in my admiration for his passionate interest in our culture and society, his revelation of his native Barbados as root and bright symbol and the unceasing formal experimenting in his verse.

"It is consoling that like Walcott (Wilson) Harris he is not lost to us, since he has passed into the consciousness of our civilisation. I will nevertheless miss him as a continuing presence in my life. Walk good, Kamau."

Poet, playwright, founder and first director of the National Heritage Library of Port of Spain Eintou Springer said Brathwaite was a great influence in her work and her life as a poet. He has done his work and done it well. He has given us a philosophy for our language and as a people.

"He glorified what he called our 'nation language'. He was a historian who dedicated a collection of history texts of people who came. I don't know if they are still being used in schools. He was a philosopher, a historian and very passionate about our language... pity that his works are not still studied in our schools. Our literature is neglected in the schools because it is what bends us to ourselves, to our beauty."

UWI Vice Chancellor Sir Hilary Beckles said Brathwaite was known as the keeper of the "abeng", the African inspired use of the conch shell to spread manifesto messages among mountain maroons and their fellow forest freedom fighters.

"The ‘abeng man’ grew a barberless beard, wore a roster of Rasta tams, sliding across our campuses, feet unchained in leathery slippers, and could never speak at a table without his thumb throbbing to the inner sound...the sound...the sound."

Recalling working together in the history department at Mona, Beckles said Brathwaite chose to live in a village on the edge of the Blue Mountains close to the maroons that preserved the land.

"He would come and go, the ‘mountain man’ with his abeng, but always writing, speaking, blowing, publishing, and calling. Primordial poet of the middle passage, and philosopher of the ‘inner plantation’, our abeng man took the words of the empire, deformed their structure, mangled and decolonised their meaning in order to promote the rebellion against the inner estate where the real bondage of his people had persisted beyond the lawless Act of 1834 that ignored ‘Ewomancipation’ for ‘Emancipation’ when women were the majority on the plantations."

Beckles was most passionate about Brathwaite's work and the impact it made on the generations of African people so many years ago, now, and for those to come in the future.

"Over the years, I watched him up close as a batsman examines a brilliant bowler and marvelled at his ancestor-given gifts. He possessed a beautifully turbulent and unpredictable mind, honed in the watery underbelly of the middle passage, daily demanding new waves washing the beaches of our minds.

"The abeng man was a soldier for our souls. For more than three scores and ten, his poetic passages told his tale. He cared for us — the used, abused and abandoned people/property of the empire. He called on us to be metamorphosed into missionaries, ontological armies marching to freedom from fear and distancing ourselves from doubt."

The TT Bocas Lit Fest has revealed that Brathwaite will posthumously be awarded the 2020 Bocas Henry Swanzy award for distinguished service to Caribbean Letters.

Organisers of the festival said Brathwaite had agreed to accept the award just days before his death. The award recognises his contribution as a literary critic, literary activist, editor and an author on topics of Caribbean literature and culture. The award was also meant to honour what would have been Brathwaite's 90th birthday.

His family will be presented with the award at the annual Kamau Brathwaite lecture on March 5. His life will also be celebrated at the tenth NGC Bocas Lit Fest which runs from May 1 to 3 in Port of Spain.

Bocas Lit Fest founder and director Marina Salandy-Brown said: "Although the Bocas Henry Swanzy award is not usually given posthumously, as it was offered and accepted by Prof Brathwaite shortly before he died, we will present the award as already planned at a ceremony in Barbados in March."

In its obituary the UK Guardian quoted American poet Adrienne Rich praising Brathwaite for his “dazzling inventive language, his tragic yet unquenchable vision, which made him one of the most compelling of late 20th century poets.”

Brathwaite began composing and performing his best-known work, The Arrivants: A New World Trilogy (1973), while teaching and studying history in Jamaica and Britain in the 1960s. This epic trilogy traces the migrations of African peoples in and from the African continent, through the sufferings of the Middle Passage and slavery, and dramatises 20th century journeys to the UK, France and the US in search of economic and psychic survival.

The Arrivants exemplified Brathwaite’s ambition to create a distinctively Caribbean form of poetry, which would celebrate Caribbean voices and language, as well as African and Caribbean rhythms evoking Ghanaian talking drums, calypso, reggae, jazz and blues. Brathwaite argued that the iambic pentameter embodied the British language and environment; it was not a meter that could carry the experience of hurricanes, slavery and a submerged African culture.

Brathwaite is survived by his second wife Beverly Reid, along with his son (with his first wife Doris who died from cancer), Michael, his granddaughter, Ayisha, and a sister, Joan.

Comments

"Celebrating Kamau Brathwaite, tributes to Caribbean literary giant"