China’s murky trail in the Caribbean

The Caribbean Investigative Journalism Network (CIJN) is a collaborative effort by reporters throughout the region, telling important stories from the Caribbean via a uniquely Caribbean perspective. The project, a digital multimedia platform, was launched on December 5.

Newsday’s associate editor for business, CARLA BRIDGLAL, was part of the inaugural team.

She, along with journalists from Guyana, Suriname and Jamaica, explored the extent and impact of China’s increasing interest and investment in the region.

The following is an abridged version. To read the entire story visit www.cijn.org.

CARLA BRIDGLAL, IVAN CAIRO, STEFFON CAMPBELL, ALIX LEWIS and NEIL MARKS

A hotel. A highway. A port. The prime minister’s house. For Caribbean countries, one of the most visible, expansive, and expensive forms of Beijing’s engagement with the region is its financing of large-scale infrastructure projects.

China’s growing economic presence in the Caribbean is readily associated with such undertakings, but a Media Institute of the Caribbean (MIC) investigation into the conduct of business with the Asian powerhouse in the region has unveiled a trail of official secrecy, questionable procurement processes and the looming threat of potentially insurmountable debt.

Economies weakened by mixed internal and exogenous economic conditions, retreating economic support from traditional multinational agencies, an appetite for high-profile “dream” projects and offers of soft repayment terms have all conspired to create entry points for a wider and deeper Chinese presence in the Caribbean.

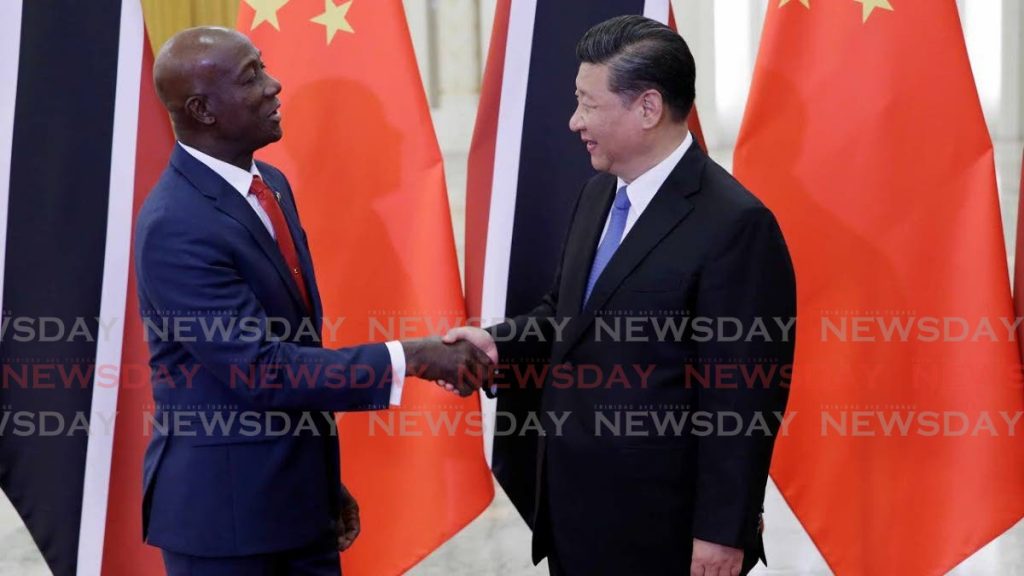

Standing on a political platform in June 2018, just a month after TT became the first country in the Caribbean to sign on to China’s US$4 trillion global development strategy, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Prime Minister described the new dynamic:

“We told them we need your investment and you need our location in the Caribbean,” Dr Rowley said.

As the world economy evolves, he continued, so too must TT: “Foreign investment came to this country from Britain and later from the United States, and all along we’ve had this foreign investment inflow. But today China is the world’s second-largest economy so while the economy of Britain drove us for a while and the US for another period, if we are to tap into serious inflows of foreign direct investment we have to look into countries that are looking for investment opportunities abroad and China is that today.”

Suriname signed on in June that year, and in August, Guyana’s then foreign minister Carl Greenidge and China’s ambassador to that country, Cui Jianchun, signed the agreement that officially drafted Guyana into the BRI.

Jamaica, the second biggest economy in the Caribbean, was relatively late to the game, finally signing on to the BRI in April 2019. Be that as it may, of Caricom's 15-member states, five have diplomatic relations with Taiwan.

Increased bilateral trade and access to China’s vast and growing economy have been the ostensible reasons for the Caribbean’s ready acceptance of the nearly US$50 billion China has made available to the region for infrastructural development.

From 2005-2018, Chinese banks (China Development Bank and China Export-Import Bank) were the largest lenders in Latin America and the Caribbean. Accumulated loans have surpassed US$140 billion. Of that, TT accessed US$2.6 billion and Jamaica, US$2.1 billion.

Over the last 25 years, China has put an estimated US$8.25 billion in the Caribbean and upcoming projects could add another US$8.92 billion.

Over the past ten years, project values have increased by 800 per cent. Most of this money comes in the form of concessional, government-to-government loans with interest rates well below market levels (some as low as two per cent) making them attractive to highly indebted, economically challenged Caribbean countries.

The Caribbean Development Bank estimates the region would need about US$30 billion to modernise its infrastructure over the next decade. With global development assistance from traditional partners drying up, Caribbean countries have readily grasped Beijing’s offer of easy financing.

The short-term benefit is obvious – a region with critically outdated infrastructure finally has the opportunity to get much-needed investment to transform and grow its means of production.

The MIC investigating team found, however, that in most instances, negotiations for these government-to-government projects and the precise terms of the agreements are not routinely publicised, leading to concerns about procurement processes and concessions related to local content, labour practices and adherence to building and other codes.

Looks good on paper

China’s Caribbean portfolio is extensive. It includes highways and bridges, housing, energy, mining, air and sea ports, tourism projects, hospitals and even official residences, forming a part of that country’s strategic thrust into Latin American and the Caribbean.

Proposed projects could offer China a strong trading foothold among tens of millions of people in Brazil’s landlocked south, via hundreds of miles of paved road through Guyana’s jungle and then off to the Caribbean Sea to a docking port in Trinidad originally intended to service ships passing through the Panama Canal.

But the Caribbean’s thirst for financing and Beijing’s style of doing business have offered up some interesting dynamics.

Legal disputes associated with the US$3.5 billion Baha Mar resort project in The Bahamas – the work of China Construction America, a subsidiary of China State Construction Engineering – led to a downgrading of the country’s S&P Global rating in 2015.

In Jamaica, a 2012 independent forensic audit of the Jamaica Development Infrastructure Programme (JDIP) and the Palisadoes Shoreline Protection and Rehabilitation Works Project concluded there was “non-adherence to allocations approved by Parliament and the Ministry of Finance. There was also the arbitrary issuance of variation orders and selection of sub-contractors along with unprogrammed and arbitrary allocation of funds for institutional strengthening,” according to the audit document.

In TT, the sudden termination of the government’s US$71.7 million project between China Gezhouba Group International Engineering Company and the Housing Development Corporation (HDC) in 2019 has drawn attention to a lack of transparency in the award of the contract, and what have been described as overly generous concessions to the Chinese company.

In Guyana, a US$150 million project to upgrade the Cheddi Jagan International Airport remains incomplete more than ten years after it began – seven years behind schedule and counting – owing to various concerns over workmanship and other technical issues.

And, in Suriname, there are fears that mounting debt to China, spanning decades, can have the impact of stalling future development and exposing the country to liabilities way in excess of its ability to pay.

The China Export-Import Bank (China EXIM), principally, and the China Development Bank (CDB) – two Chinese state-owned banks – have been responsible for a large proportion of Chinese concessional loans in support of Caribbean projects.

The banks administer such foreign aid loans using subsidies from China’s foreign aid budget in order to soften lending terms.

Soft diplomacy, hard consequences

Caribbean governments, however, resist the notion that Chinese funding is an avenue for Chinese hegemony in the region.

Just after Guyana signed on to the BRI, President David Granger shut down suggestions of a potential debt trap, insisting Guyana had signed on with its “eyes wide open.”

If Chinese funding is available, he insisted, it will be sought. “Our longest river is 1,000 kilometres long – the Essequibo – but there is not a single bridge,” Granger told journalists. “We have to build a bridge. We (also) have to build a railway or a road link to the Rupununi which is our largest region.”

Guyana is on the cusp of a life-altering economic transformation, with its first commercial oil production coming on stream in December 2019.

The International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook for October 2019 projects the Guyanese economy will grow over 85 per cent in the next year. Until then, the South American country is still strapped for cash to devote to infrastructure.

“We cannot develop without infrastructure and we just do not have the capital to do it on our own. So whether it comes from America, China or Britain we have to have it, and of course we have to look for the best deal,” Granger said.

China’s economic engagement could have potential harmful effects, especially for those who have amassed unsustainable levels of debt to China, leaving those economies at risk of becoming less competitive in manufacturing and agricultural technologies and more dependent upon commodities exports to China and elsewhere. There is also the concern that Chinese support extends a lifeline to leaders with poor records of governance and can exacerbate corruption.

The devil is always in the details, and, as Dr Evan Ellis, a research professor of Latin American studies at the Strategic Studies Institute of the US Army War College who focuses on the region’s relationship with China, points out, the Chinese are skilled negotiators and if partners aren’t paying attention there’s plenty chance of things going awry.

China’s engagement in the region isn’t necessarily negative but it is a difficult sort of relationship one has to go into with strong governance and a lot of transparency and good planning to get the best deal, he said.

While that’s not to say these projects are bad, there are some red flags, he said, because of how easy the Chinese make it to access these loans.

“Traditional multilateral institutions like the IMF or World Bank force you to show you have a business plan and credible model as well as environmental compliance, etc. The Chinese, if they can assure they can get repaid in one way or another they don’t necessarily need to satisfy themselves that the investment itself makes sense.”

Dealmakers that should have been deal-breakers

During the course of this investigation, the MIC team examined contracts that, in some cases, were only made public through leaks or freedom of information requests, paying special attention to waivers, arbitration and concessions.

In many cases, some governments have withheld contracts and agreements from the public.

And, in the case of TT, senior government ministers spanning different political administrations even confessed to not having viewed final documentation, despite giving their approval in Cabinet.

Waivers, arbitration and concessions

Waivers of some rights have been found to be standard in contracts of the magnitude China has signed with the Caribbean.

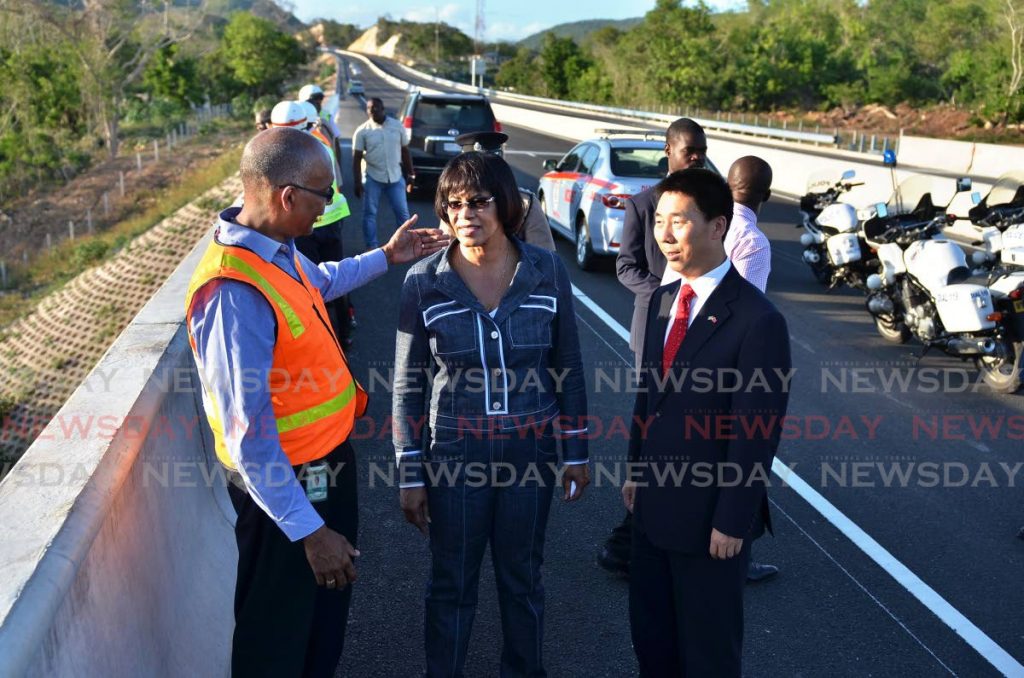

In the case of Jamaica, for the US$630 million North-South Highway project signed with China Harbour Engineering Corporation (CHEC) on June 21, 2012, the government exposed itself to significant debt.

This risk is something Prof Craig Clarke, lecturer in the Department of Government at the University of the West Indies, finds hard to grapple with.

The clause speaks specifically to the implication of a possible breach of contract on the part of the Government of Jamaica or such cases where actions of the Jamaica government result in losses to the CHEC, he told MIC.

“When contextualised, the clause – which requires that the GOJ forfeit any asset currently owned or assets owned in the future – could prove instrumental in debt recovery by asset seizure,” Craig said.

It is not the just debt recovery that bothers Clarke. The clause essentially makes all publicly-owned assets in Jamaica accessible to seizure.

“This means the national water infrastructure, for example, could be claimed as part of the repayment mechanism. And that is a very scary thought.”

The onus then, Clarke posits, is on the government of Jamaica to “ensure that there is no circumstance where this clause become actionable.”

Similarly, the US$46.7 million contract, funded by the Eximbank for a road improvement project in Guyana, signed on January 9, 2017, says in Article 8.1:

“The borrower hereby irrevocably waives any immunity on the grounds of sovereignty or otherwise for itself or its property in connection with any arbitration proceeding…or with the enforcement of any arbitral award pursuant thereto.”

Guyanese attorney Shivanie Lalaram said sovereign immunity is a state’s freedom from being subject to the legislative, judicial and administrative powers of another state.

“In waiving its immunity, Guyana is submitting itself to the jurisdiction of China. Therefore, the municipal laws of Guyana that would have related to the agreement would not apply,” Lalaram explained.

Sydney Armstrong, head of the Department of Economics at the University of Guyana, sees this clause and others in the contract as putting countries at significant risk in the event of late payments or a lack of payment, for whatever reason.

“The seriousness of this clause is underscored by the fact that these roads (as in Guyana’s case) and ports are often times critical for the proper functioning of the economy and if controlled by a foreign entity can hinder the economic progress of the nation. This is extremely worrying,” Armstrong said.

Attorney and chartered accountant Christopher Ram describes Article 8.1 as being “the essence of the Sri Lankan experience” whereby China could take control of Guyana’s assets. Sri Lanka is frequently referred to as an example of China’s global “debt trap” after that country’s inability to repay its debt US$1.12 billion debt allowed China to negotiate a 99-year lease arrangement for its Hambantota port, strategically located on the Indian Ocean, as an exchange.

“(This) is Guyana dangerously agreeing to cede sovereignty. It plays into the Chinese strategy of using economic weaponry in the pursuit of influence and domination,” Ram said.

In the case of the Guyana East Coast Demerara Highway Project, at Article 8.4, Guyana has expressly agreed to be subject to the laws of China, which may include financing laws.

“Therefore, if dispute arises pursuant to the agreement, these disputes will be determined by the laws of China as applicable to the agreement,” says Lalaram.

Article 8.5 stipulates that in the event of arbitration, parties have to submit their dispute to China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC) and the arbitration process will be govern by Chinese laws and the hearing held in Beijing.

“This here goes against the fundamental principles of arbitration,” Armstrong said. For arbitration to work, he argues, it should be conducted by a neutral party.

It should also be conducted in a neutral territory to avoid any bullying or bias.

There is some precedent in the Caribbean to warrant this scepticism: when the Baha Mar project, a US$3.5 billion resort touted as the biggest in the Caribbean, went into bankruptcy proceedings, the contract stipulated resolution in Hong Kong, putting Swiss-born developer Sarkis Izmirlian, who had conceptualised the project at a disadvantage.

He eventually lost his US$800 million-plus investment. The project was eventually sold to Chow Tai Fook Enterprises Ltd, a Hong Kong conglomerate with significant real estate holdings and ties to Beijing.

Regional governments and China, meanwhile, reject any suggestions that the terms of the contracts or the financing terms could lead to seizure of assets by China.

“China doesn’t have this culture of taking over others’ things,” Zhang Jinxiong, a former Chinese ambassador to Suriname, told MIC.

“In connection with the question of taking over, I would like to add (that) the Chinese never think of that and we don’t do that.”

China is now the lead development partner for Suriname. According to Zhang, there should be even more Chinese investments in Suriname.

“Actually, we should encourage more investments from China in Suriname. When you look at the development here in the past 20 years, you have more and better roads, better quality of life. That is good for Suriname. So why are Surinamers so afraid of that?”

Since the Bouterse administration came into office in 2010, financial cooperation between Suriname and China has accelerated to a large extent because the Netherlands has essentially withdrawn developmental aid, preferring not to have relations with Bouterse, who has been convicted and sentenced, in absentia, on charges of drug trafficking.

China appears to have willingly filled the void, and has provided various concessional loans and donations to Suriname over the past nine years. But most of the details of the deals cut between Chinese companies and the government remain tightly-guarded secrets. Typically, loan amounts, grace periods, interest rates and the duration of projects are the only information publicly released.

In TT, among the basket of trade-deal goodies negotiated by the government and China during that official visit last year was a US$500 million dry-docking facility in the village of La Brea, an industrial park in Phoenix Park, Point Lisas.

Desperate to create new opportunities, especially in the southern half of the island following the closure of the 101-year-old Pointe-a-Pierre oil refinery, the government insists that TT is getting the best possible deal.

“We are different to Sri Lanka,” the Prime Minister told reporters in defence of such a possibility regarding the La Brea Industrial Park project. China Harbour Engineering, the contractor, will have a 30 per cent stake.

The details of the project are not yet available, though the project should have started before year's end. “We wanted an equity partner to share the cost and the risk of making the business succeed,” Dr Rowley said.

“I understand with the closure of Petrotrin there’s a need for employment, but the question is, if you are a shipping company, I’m not sure research has been done (about La Brea’s viability). It’s a relatively expensive port in terms of pay rates that’s basically in the middle of your transit. It’s not a place where a shipping line would naturally do repairs,” Ellis said.

With the Phoenix Park industrial project, he notes that his understanding is the government spends something like a billion dollars in local currency for a project that is 40 per cent done by a Chinese contractor, with the general promise that maybe 60 companies will set up. The government has insisted there are ten Chinese tech firms already lined up as guaranteed tenants.

“But the question,” Ellis said, “is there a contractual stipulation that the Chinese companies will actually come out, or is it just a general hope, and will the TT government, therefore, find itself pressured to offer special labour zones or other concessions?

“At the end of the day, for me, a lot of projects work out like this. When you don’t do it with enough attention to legal details or planning, and it’s too easy to get the money, you can commit public funds in a way that can prejudice the country and benefit the Chinese company.”

The projects are already off to a late start, despite continued assurances and several memoranda of agreement. For the Phoenix Park Industrial Estate, which was initially scheduled to start last December, the governments of TT and China only on November 13 signed another MoA, this time for a “framework agreement” for a concessional US$15.4 million loan for the project.

But despite the grandeur of a signing ceremony, key details were still vague. Asked specifically what were the time frame for repayment, interest rate, and terms and conditions of the loan, Trade Minister Paula Gopee-Scoon told the TT Newsday, “That is still (a matter) for the Ministry of Finance in their negotiations with the China Exim Bank.”

She added: “It’s a concessional loan, so I’m sure it’s at a very low-interest rate, but it is a matter for the Ministry of Finance in their negotiations.”

The Summary Economic Indicator bulletin from the Central Bank puts TT’s total public-sector debt for 2018 at US$18 billion, or 60.7 per cent of GDP; of that, US$325 million is owed to China, the government disclosed last year. With the new projects in the pipeline, that estimate is now reportedly over US$890 million.

Comments

"China’s murky trail in the Caribbean"