If these cul-de-sacs could talk

If these cul-de-sacs could talk, they would tell you to never leave home. Would they be right?

The quiet privacy of a dead-end road, with a cul-de-sac at the end, brings up thoughts of the laughter of children and grassy lawns, and an illusory sense of security from the harms of the outside world.

Search online for the benefits of cul-de-sacs, and you will immediately find a barrage of information telling you they are safer than the through-streets found in a well-connected urban grid system. It seems logical then, that as a policy we should be encouraging this layout of streets in our neighbourhoods. That is exactly what our planning system and many of the allied professionals who influence the design of subdivision layouts continue to encourage and promote.

However, a study done in London (Hillier and Sahbaz, 2006) looked specifically at crime, population density, and street layout, among other factors. This detailed study found that burglaries are fewer on densely populated through-streets than on sparsely populated streets in areas with a less grid-like (more cul-de-sac-like) layout.

Urban planning and policy researcher Todd Litman, in a blog post for Planetizen, Planning for Crime Reduction, says, “few issues are more emotional, and therefore vulnerable to bad analysis, than urban crime risk. Solid research indicates that more compact and mixed development tends to increase neighbourhood security.” This is in stark contrast to the perceived safety of the low-density, residential suburb with its characteristic cul-de-sac streets – the widespread gold standard here in TT.

Litman points out that there are two types of factors that are behind this disconnect in understanding the relationship between urban form and crime.

The first factor is demographics. Rates of crime are influenced by socioeconomic factors such as age, income, employment status, and education. It also turns out that those who, according to demographic factors, are less prone to commit certain types of violent and property crimes are also more likely to self-sort into homogeneous enclaves (typically) in low-density areas – making these places seem safer.

The second factor is land use. Commercial uses, such as banks and liquor stores, which are typically less frequent in more suburban areas, are associated with higher rates of crime.

Therefore, studies that do not account for socioeconomic factors and land uses can give a skewed picture of crime. What they may simply show is that criminal activity has shifted elsewhere, not that it disappears. In other words, you may be a little safer as long as you never need to leave your residential cul-de-sac.

Studies – like the London one above – that account (control) for socioeconomic factors and land uses tell a different tale. It turns out, that those mixed-use and dense urban areas with dreaded crime-prone commercial uses and unsavoury grid-like street patterns are quite beneficial.

According to Litman, a study in Chicago – a US city with a reputation for high levels of crime – showed “crime rates increase near commercial land uses, particularly bars and liquor stores, but this effect is (strongly) offset by population density; dense mixed-use areas are safer than typical residential areas.”

Another study in Philadelphia – also with a reputation for crime – found that while places with commercial establishments do experience higher rates of assaults and robberies, these rates are lower in places where businesses are open for more hours per week (more human activity).

The London study further found that for areas with commercial uses, safety increased with higher intensities of accompanying residential activity.

Of course, as Litman also notes, crime is not the only danger that we face. The less grid-like a street system is, the more we have to drive, and the more we depend on dangerous arterial (main) roads to get around. The data shows that areas with cul-de-sac layouts are associated with significantly higher traffic fatality rates.

In 2008, National Geographic’s James Owen wrote, “most large, captive-bred carnivores die if returned to their natural habitat, a new study has found.”

Those that isolate themselves within the perceived safety of a cul-de-sac are far more vulnerable to danger as soon as they leave, because of the problems created by that false sanctuary.

In TT we are building new low-density, disconnected suburban neighbourhoods en masse, and simultaneously trying to impose suburban design qualities onto our already fragile cities.

By trying to disconnect ourselves from the physical and metaphorical grid and segregating land uses, we increase our vulnerability to harm should we need to reconnect.

Wesley Marshall, a civil engineering professor at the University of Colorado, remarks, “A lot of people feel that they want to live in a cul-de-sac, they feel like it’s a safer place to be…but if you actually move around town like a normal person, your town as a whole is much more dangerous.”

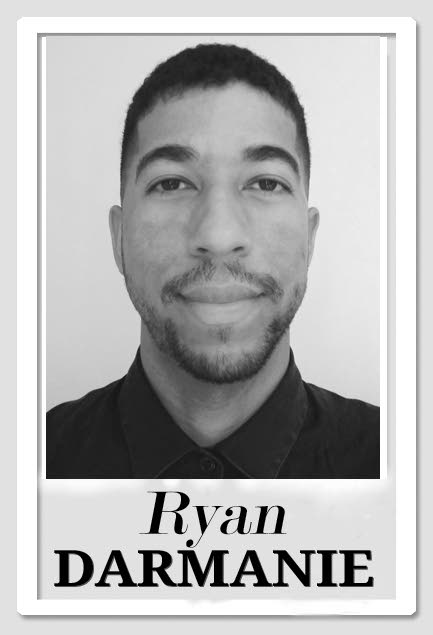

Ryan Darmanie is a professional urban planning and design consultant, and an avid observer of people, their habitat, and the resulting socio-economic and political dynamics. You can connect with him at darmanieplanningdesign.com or e-mail him at ryan@darmanieplanningdesign.com

Comments

"If these cul-de-sacs could talk"