Saving the Toco Folk Museum

SHEREEN ANN ALI

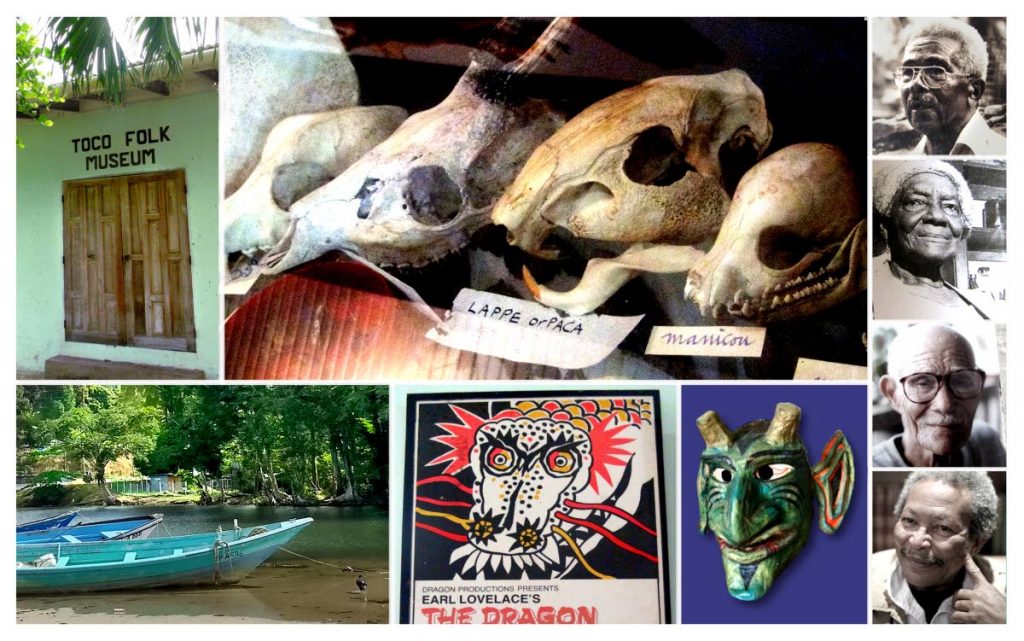

SALYBIA, Rampanalgas, Morne Cabrite, Grande Riviere: the names roll off the tongue like an incantation of remote, wild beauty. Northeast Trinidad is a place of lush primary rainforest, mountains, rivers and seascapes, home to biodiverse life forms and the descendants of a mixture of First Peoples, Spaniards, Africans, French Creoles and others who chose to make a life here. Like a window into this world, the Toco Folk Museum reflects and refracts some of the area’s many-layered stories through its thoughtful displays and projects, sharing folk knowledge, natural history and insights that both chronicle and celebrate life in northeast Trinidad. But today, it is struggling to survive.

The 22-year-old museum is currently at the Toco Secondary School, which was badly hit by the 2018 earthquake. The earthquake severely damaged many school buildings, and though it did not damage the museum structure itself, it’s one of several reasons the museum is seeking a new home with better public access.

“The museum collection focuses on the culture, history and environment of the northeast coast. It has been slowly amassed over the years as visitors entrusted precious items to us,” said curator and museum co-founder Nemme McSweeney in a recent Newsday interview in Toco. “But we are about to face closure and the break-up of our exceptional artefact collection unless we can get necessary assistance and partners to take us to our intended goal.”

That intended goal includes a three-phased, five-year expansion project to rebuild the museum into an engaging cultural, intellectual and entrepreneurial centre where visitors and local residents alike may gather to educate themselves about the history, ecology and treasures of the northeast region.

A new museum would fulfil the role of Heritage Centre cited in the Sangre Grande Municipal Development Plan 2010-2020, part of an overall plan for developing ecotourism in the area.

The museum could become the model for a network of community museums overseen by the National Trust, believes the curator. McSweeney envisages a welcoming, modern walk-in centre for residents and visitors open at least four days a week. She sees the potential to offer a broad range of learning experiences such as performances, exhibitions, films and workshops on many topics such as organic agriculture, papermaking, mas crafts, bio-buildings and northeast Trinidad bird life.

Museum activities could also nurture local innovation by encouraging area inventors to adapt indigenous knowledge to develop pioneering industries, said McSweeney, who gave an example: “One Cumana resident, Denton Bruno, has already modified a washing machine and created other devices to make cassava processing easier, and his cassava bread is assured a local market as far as Tobago.”

Northeast Trinidad, which the museum serves, is a large area. It spans more than 13 villages from Matura on the east coast to Matelot on the north coast, and includes the Matura National Park, a 22,239-acre region of primary tropical forest, mountains and rivers that is home to rare and endangered wildlife, including the pawi and the ocelot. The Toco Folk Museum wishes to be a connecting link bringing together people from remote villages and strengthening community ties within the northeast, even as it helps to develop people’s intellectual and creative horizons.Migrants seeking a fresh start have long found refuge in Toco’s remote beauty, helping to define its culture: “The first inhabitants were the Amerindians, then came the Spanish, later the French who opened up cocoa and coffee plantations. Labourers to work these came from Venezuela, Martinique, Tobago, Grenada and elsewhere, and many Chinese also settled here, providing goods and services needed on these estates,” said McSweeney.

Some like the Venezuelans and Martinicans brought valuable knowledge of medicinal plants. Herbalist Albertina Pavy lived in Toco and supplied the museum with a huge array of medicinal herbs including some lesser known ones like matrank, cancanapiray, tref and japana which the UWI Botany Department acquired for their planned Physic Garden.

Northeast Trinidad’s stories are varied, from the Carinepagoto indigenous First Peoples to the fury of World War II battles off Galera Point. The region has been home to Spiritual Baptist traditions and a magnet for a range of artists and writers who found solace and inspiration there, including Earl Lovelace, Derek Walcott and Toco artist Marcelio “Boboy” Hovell. When cocoa was king, a lot of it was grown in Toco, too, on estates like La Nourice and Aragua.

Many citizens may not know that during the lean years of the Second World War, with embargoes on imports of staples like rice and wheat, northeast Trinidad supplied tons of yam, dasheen and other ground provisions from its war gardens and helped to feed the fledgling nation.

People from northeast Trinidad once grew and traded coffee, cocoa, coconuts, citrus, cotton, nutmeg and tonka beans. Through workshops, a new Toco Folk Museum hopes to educate the farming community on permaculture, promoting organic agriculture, said McSweeney.

The museum’s eclectic artefacts range from vintage photographs to material on musical traditions, folklore, culinary heritage, indigenous money management, handicraft traditions, the Trinidad Railway story, and sporting excellence (2012 Olympic javelin gold medallist Keshorn Walcott is from Toco).

McSweeney recalled the donation of a ship’s anchor collected in fishermen’s nets off Galera Point. The museum invited Gaylord Kelshall of the Chaguaramas Military Museum to examine it. He dated the anchor to pre-1900 and wrote a paper on the military history of Toco 1699-1983, which records that Galera Point became known as Torpedo Junction during World War II, owing to the German U-Boats battling American supply ships. The wreck of the Norwegian tanker Nordvangen, torpedoed in 1942, still rests there. The Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm built the Toco airstrip.

Northeast Trinidad’s artistic heritage includes musical traditions of bongo wakes, string bands and songs by famed parandero Pedrito Marcano while the late pioneer panmaker Ellie Mannette hailed originally from Sans Souci.

In Carnival arts and crafts, one can see work by famous masman Narrie Approo, whose wonderful papier mache masks and costumes are a delight to behold. There is also work by Cito Velasquez and Senor Gomez as well as original handwritten speeches of the Great Midnight Robber Andrew “Puggy” Joseph.

The museum’s artefact collection is perhaps strongest in the area of natural history. The Matura National Park contains pristine tracts of forest which protect an invaluable watershed and waterfalls such as Rio Seco, Mermaid Pool, Shark and Grande Riviere. You can find seashells, dolphin skulls, local wildlife imagery and jewel-coloured beetle carapaces among the exhibits.

Off the coast, McSweeney notes: “The Fringing Salybia Reef System is the rich feeding ground of five of the world’s endangered sea turtles, which also nest on these beaches. The Salybia Fringing Reef curves all the way to Galera Point, and the area is home to bizarre creatures like the long-nosed batfish, mantis shrimp, flying gurnards, stoplight parrotfishes and honeycomb cowfish.”

McSweeney is firmly convinced that ecotourism is the way to go in northeast Trinidad, and that the museum can play an educational role in this. She cited conservationist Gary Aboud, who in a radio talk show earlier this year noted that tourism in general is often large-scale, exclusive, land-hungry and offers largely menial work to residents, whereas ecotourism is small scale, respectful of the host community and interested to learn about it, and encourages residents to improve their knowledge, inculcating a sense of self-worth.

McSweeney and a colleague, Gabriel John, along with some motivated students, conceived the idea of a museum back in 1994. Among many people who helped to support it were community elder Victoria “Thora” Thomas, artist Marcelio Hovell, fisherman Sayeed Mohammed, Cumana artist Cyprian Rivers, schoolteacher Clarita Thomas, Richard Nero and Albertina Pavy, as well as Edward Hernandez, the deceased curator of the Tobago Museum, who provided invaluable advice.

For McSweeney, great things often start in small ways. Many people scarcely understand or value the good things they may already possess or have access to right in their own home environments. This includes the myriad gifts of nature as well as the rich life lessons and creations of diverse people who worked, invented, strived and thrived in northeast Trinidad. McSweeney dreams of a new Toco Folk Museum passing on some of these invaluable lessons, becoming a special place to learn, enjoy, share community spirit, and even help incubate new skills and livelihoods.

MORE INFO: See the 2012 four-minute video Toco Folk Museum Hidden Treasures at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J8j4n5gcJrM

To contact Nemme McSweeney for offers of partnerships, funding or other collaborations towards a new, relocated Toco Folk Museum, please call 315-8682 or e-mail nimmimcsweeney@live.com

Comments

"Saving the Toco Folk Museum"