Caricom for the people

Former Jamaica prime minister PJ Patterson, who came to Trinidad for cricket, last weekend, shares his views about the future region, as well as his memoir, in a two-part interview starting today.

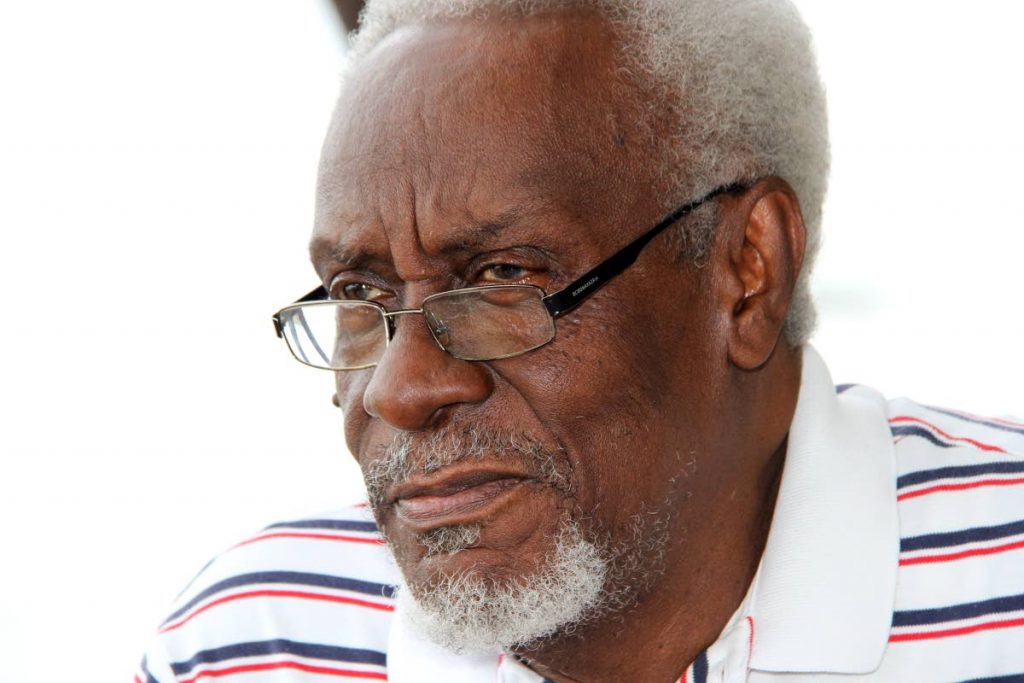

With his grey hair, contemplative gaze and regal bearing, PJ Patterson (Percival Noel James Patterson) resembles those sages that have long peopled West-Indian novels.

And for all intents and purposes, Patterson, 83, remains just that–a wise voice–some 12 years after leaving office as Jamaica’s seventh prime minister and, up until now, its longest-serving head of government.

Patterson served as the island’s prime minister from 1992 to 2006, rising to office as leader of the People’s National Party (PNP), a party that has had mixed fortunes in Jamaica.

Regarded as one of the Caribbean’s leading regionalists, Patterson, now in retirement, has continued to seek the advancement of West-Indian peoples in several areas, including sport, for which he maintains a passionate interest.

Case in point: he was recently in TT as chairman of the Cricket Tournament Committee, a body which oversaw the Cricket Professional League (CPL) for the Caribbean. The committee comprises three members chosen by Cricket West Indies Ltd, three by the CPL and an independent chairman.

Patterson attended the semi-final games in Guyana and the semi-finals and finals, which took place at the Brian Lara Academy, Tarouba, on Sunday.

But he is also concerned about broader issues, most notably the inter-reliance, or lack thereof, that exists between Caribbean territories through Caricom (Caribbean Community and Common Market), for which he remains a staunch proponent.

In a wide-ranging Sunday Newsday interview on Monday at the Hyatt Regency Hotel, Port of Spain, Patterson was cautiously optimistic about the future of the organisation.

“Until recently, there was reason to fear that Caricom was not getting the impetus of leadership which is required to move the integration process forward but in the last year or so, some very encouraging signs have emerged,” he said, alluding to the 39th regular meeting of heads of government in Jamaica, in July, where, among other agreements, a decision was taken to revitalise the Caricom Single Market and Economy (CSME).

Patterson regarded the CSME as “the main engine that must carry the integration movement forward.”

He said a follow-up meeting has since been held in Barbados which has not only identified what the concerns are but has begun to outline steps which are necessary in the short term to make the single market a reality.

“One must look forward to see the extent to which this will materialise into reviving a national movement,” he said.

However, the former PM warned that regional leaders should not promote selfish agendas.

“I don’t think we should ever forget that for Caricom to be meaningful, it is not about the governments. It’s about the people. They must feel that Caricom matters to them and there are some things that have to be done,” he said. These, he envisages, include the facilitation of travel between the islands.

“Here, I am not only talking about the air or sea transportation which are critical elements,” he pointed out, “I am talking about the question of how we treat one-another in our ports of entry.”

Patterson said a well-oiled Caricom must also look at security and the economic challenges confronting the region.

“Virtually, every single nation in the Caribbean is presently confronted with economic challenges, maybe of different levels of intensity,” he observed.

Of the latter, he added: “What I think we need to be doing more and more is looking at how do we combine our efforts in our relationships to make our voices more effectively heard in the corridors of international economic decision-making. Here, I am referring to some new issues that are arising in respect of money and banking transactions. We are working towards a common position on it. We have to keep on working.”

Patterson also mentioned energy as a major challenge, saying most Caricom territories were deficient in these areas.

“Increasingly, we have to rely on natural sources–wind, solar, water-generated. But the world is changing, and we can’t continue to do things simply because we are in the habit of doing them. We have to find new ways, new mechanisms of what we need to do for the development of the Caribbean people.”

Is there a genuine commitment by leaders to develop Caricom?

“The rhetoric is appearing to reflect a conviction that something needs to happen. We have to watch how things unfold. Let them put it straight on the table.”

Patterson claimed the Caribbean has been “grappling” with the system of governance in the region. He recalled the first meeting he attended in TT after becoming Jamaica’s prime minister in 1992, the Shridath Ramphal Report titled a Time for Action, compiled by a group of Caribbean “wise men”, was presented to no avail.

Patterson also noted that at the last meeting over which he presided, “things never happened in the way we had decided” in relation to the Rose Hall Declaration.

In the past, Patterson has been quoted as describing the declaration as Caricom’s “guiding light” in strengthening the organisatioin’s machinery and deepening the integration process, but which also served as a platform for “constant review and adjustment, to ensure efficiency in the management of the Caribbean’s affairs.”

Patterson told Sunday Newsday: “We have failed to put in place a system of governance that works effectively for ensuring that decisions, once taken, are implemented by national governments.”

However, Patterson believes there was a recognition of this shortcoming at the July conference in Jamaica.

“I have the hope, which I hope will develop into a reasonable expectation shortly, that something will be done to repair this “glaring defect.”

A lawyer by profession, Patterson was born in a small village in western Jamaica on April 10, 1935, his family rooted in education and the church.

During his childhood, he was exposed to Jamaica’s struggles for independence from Britain through the island’s two major political parties: PNP and Jamaican Labour Party. Jamaica gained independence in 1962.

Patterson’s fervour was nurtured at the Mona campus of the University of the West Indies and later, London School of Economics. Years later, it would result in the soft-spoken Patterson becoming the seventh prime minister of the island, ending a tradition that had been dominated largely by blustering orators, including former PM Norman Manley, one of his mentors.

Manley, founded the PNP and went on to serve as prime minister from 1959 to 1962. Manley's son, Michael, who followed in his father's footsteps, served two stints as PM from 1972 to 1980 and from 1989 to 1992.

Patterson recalled that at the time he assumed office, Jamaica had faced serious economic challenges. He said his government was tasked with the responsibility to make the island, the second largest in the Caribbean, adjust to the realities of globalisation. The measures, he said, have since yielded much benefit, putting Jamaica on a consistent growth path.

“We undertook the steps which were necessary for transforming the economy from one that was dependent on a limited range of products into one that has been diversified considerably, and put in place the mechanism which enabled us to enjoy economic stability, and now put on a path where, hopefully, we will be able to realise levels of economic growth which have eluded us for quite some time.”

Patterson said there was a “common acceptance” between the two main parties of the principles which are needed to govern the process of Jamaica’s economic policies and development.

“And despite the changes which have taken place in governments since my retirement,” he said, “I would say that Jamaica is now on the track for realising the benefits of the structural adjustment mechanisms that have been put in place over many years.”

Even so, Patterson admitted that crime, long a bugbear for the Andrew Holness administration, remains one of Jamaica’s more pressing challenges.

He observed while it was not a new phenomenon, “we have been trying to grapple with the monster of crime and violence. It’s not confined to Jamaica, but we have to deal with it.”

Patterson said during his stint in Caricom, leaders had recognised the need to pool their resources and knowledge to introduce co-operation between their respective security forces to address the scourge of crime, which, he noted, was occasioned by the production of narcotics and the region’s strategic location as a point of transit between the drug-producing countries south of Jamaica and the markets of the United States.

And while he is pleased with the state of emergency that has been instituted by the Holness government in St James parish to curb murders and other violent crime, Patterson said more still needs to be done.

“We have witnessed some reduction in the levels of crime in those areas, but I think it would be admitted that even with those levels of reduction, it is still too high so long as human lives are being destroyed.” Patterson said apart from social factors, there was also a need for new technology in the fight against crime. “My very strong view is that crime is one those issues that is of much too great importance to become a political football.”

He added: “I think it really is essential in all our countries that government and opposition and civil society work together as one because it is something that permeates the entire society.

“Nobody is safe, nobody is immune and, therefore, while it is accepted that the government has a lead role to play, I think that all other elements in the society have to contribute to the eradication of crime and getting it to tolerable and acceptable levels in a society such as ours.”

Caricom Single Market and Economy

The Caricom Single Market and Economy (CSME) is an integrated, market initiative which offers the people of the Caribbean Community more and better opportunities to produce and sell goods and services, attract investment and increase competitiveness. It’s ultimate aim is to create a single economic space.

It was conceptualised at the tenth Meeting of the Conference of Heads in Grenada in 1990 and comprises 12 member-states, including TT.

At a Caricom prime-ministerial sub-committee meeting in Barbados, under chairman Mia Mottley, earlier this month, heads agreed to make the CSME more effective.

The meeting followed agreement by Caricom heads at the July summit in Montego Bay, Jamaica, that there should be more frequent engagements by the sub-committee in recognition of the need for more intense focus on the CSME.

Caricom Secretary General Irwin La Rocque told the meeting there was need for member-states to ensure the implementation of agreed commitments and obligations.

La Rocque called for consultations at both the national and regional levels to involve the private sector, labour, the youth and other stakeholders more intimately in the implementation process.

Rose Hall Declaration

The Rose Hall Declaration (Montego Bay, Jamaica) on Regional Governance and Integrated Development was adopted on the 30th anniversary of Caricom at the 24th Meeting of the Conference of Heads in July 2003.

The meeting was chaired by Jamaica's prime minister PJ Patterson.

It was regarded as a ground-breaking declaration to help make a reality, the vision of a seamless regional economy serving, in all areas.

The nine-point declaration included plans to establish a Caricom Commission, or a similar mechanism, with powers to exercise “full-time executive responsibility” for furthering implementation of "community decisions.”

The proposal was set against the framework of major recommendations of the 1992 report of The West Indian Commission.

To this day, the declaration is yet to achieve its goal.

Comments

"Caricom for the people"