John Hearne’s Wide Caribbean

KEITH JARDIM

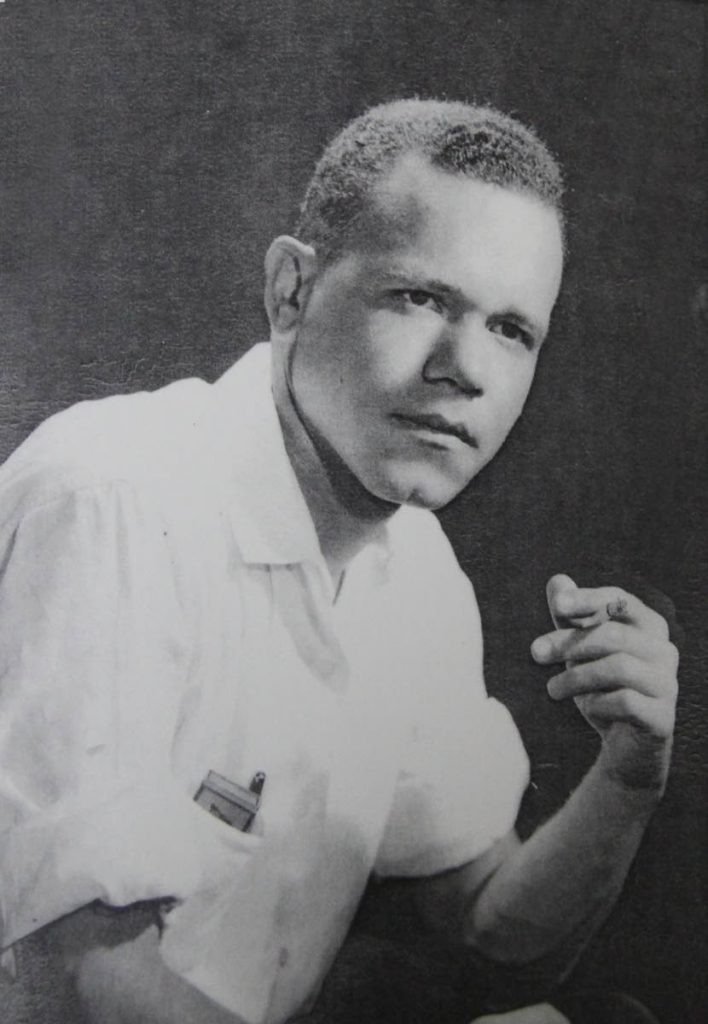

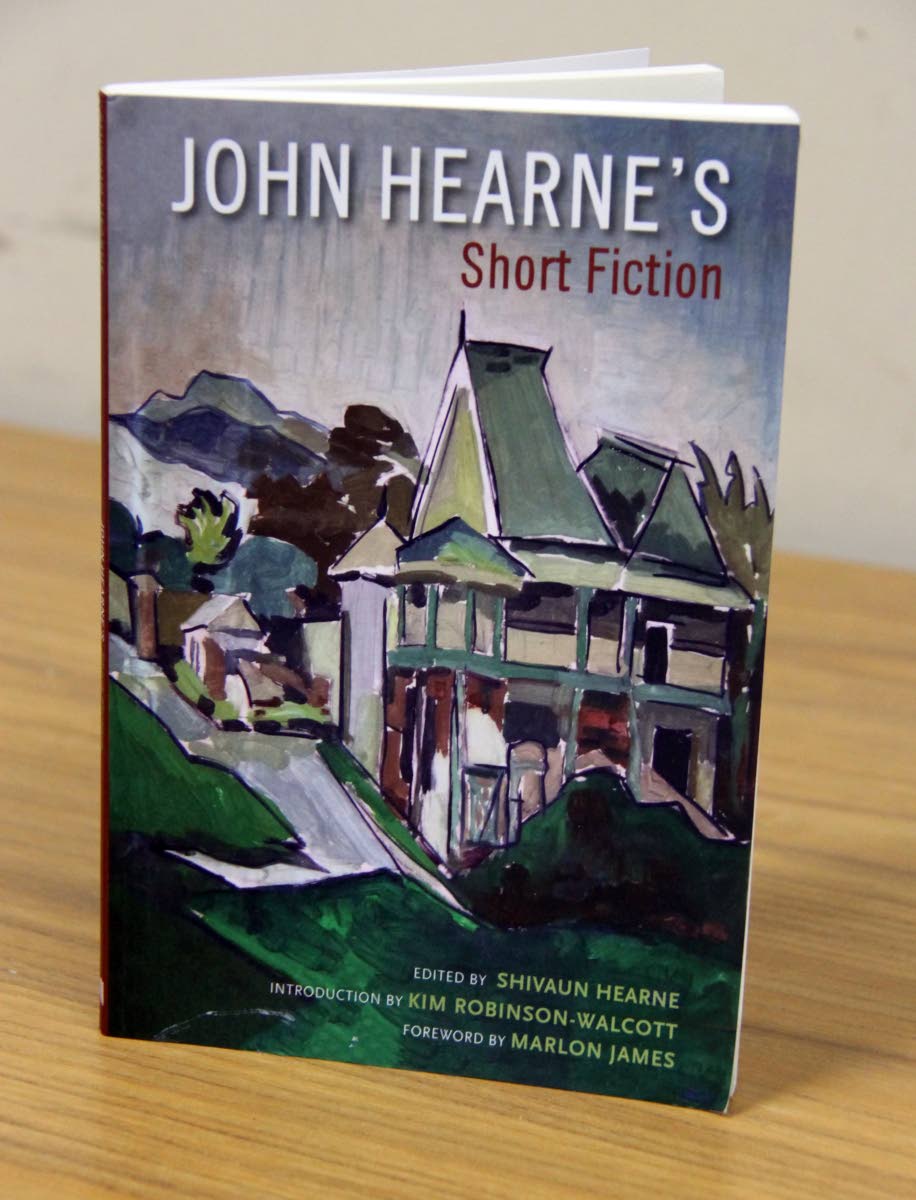

John Hearne (1926-1994) was a novelist from Jamaica who distinguished himself early in his career (Voices Under the Window, Stranger at the Gate, Land of the Living, The Faces of Love, Autumn Equinox), and his short stories, like the novels with the exception of The Sure Salvation (1981), span his most creative period – the 1950s and early 60s. Included in this impressive volume are three fine essays: a foreword by Marlon James, a preface by Shivaun Hearne, and an introduction by Kim Robinson-Walcott.

Hearne was James’s first serious fiction teacher, at the Philip Sherlock Centre for the Creative Arts in Jamaica. The Booker-Prize-winning novelist recalls Hearne’s responses to his purple prose and assesses his importance as a Caribbean writer. Shivaun Hearne, his daughter, discusses republishing Hearne’s novels. There’s more detail in her book, John Hearne’s Life and Work: A Critical Biographical Study. Robinson-Walcott’s solid argument for a serious critical reconsideration of Hearne’s oeuvre shows how the failures of independence in the region contributed to misreading and sidelining Hearne’s work, and why Hearne, for all the best reasons, is a pan-Caribbeanist.

Apart from The Bridge, a beautiful story that could have been written by Paul Cezanne, the stories are set in Guyana, Trinidad and versions of Jamaica. All these stories are well worth reading and rereading; there are brilliant examples of the form here: A Village Tragedy, At the Stelling, The Wind in This Corner, The Lost Country, Living Out the Winter, and Reckonings. At the Stelling, selected by Kenneth Ramchand for Best West Indian Stories (1982), is a Guyanese-set river adventure that achieves the unforgettable by skilfully breaking a major short story rule; and Hearne breaks it not once, twice, or five times, but nine by my count. Only other short-story masters like Flannery O’Connor, Faulkner and Marquez can do it, and no one to my mind more than Hearne in At the Stelling. Genius sees boundaries and knows how to cross them with profound success.

Trinidadians get a just lashing in Living Out the Winter, in which a writer, loosely based on Hearne, observes the decline of the Ramesars in St Clair. “If you live in Trinidad for three days you must learn to resist constant invitations to join an urbane and heartless conspiracy. A frivolous and expert malice is inherited by every Trinidadian like some honorary but unsupported title.” The story’s superb description renews your faith in the livingness of the world, but not in Trinidadians.

The Lost Country, again Guyana-set and one of my favourites, shows Hearne’s deep understanding of the natural world, his love of Guyana and the people who inhabit its interior. When I first read it so many years ago, far away in a bleak winter, I wept with joy. It has a giant heart and vision, a sacred beauty, a gift of life not seen much any more in fiction today.

Shivaun Hearne concludes her preface by quoting Derek Walcott on Hearne’s work: “In his writing, he was alone on his own road//his prose rustling from a tall cedar, and that road without question cut through the heart of the Caribbean.” True words.

John Hearne’s Short Fiction. UWI Press. 125 pages.

Keith Jardim is the author of the story collection Near Open Water; he’ll be teaching fiction workshops at the Naipaul House in St James later this month.

Comments

"John Hearne’s Wide Caribbean"