Reading and our black youths

During the sod-turning ceremony last Wednesday for the construction of the $42 million La Horquetta Public Library, Symon de Nobriga, Minister of Communication and Minister in the Office of the Prime Minister said: “Modern libraries are not just storehouses for books, but instead, they are all about providing equal and equitable access for all and levelling the playing field for school children from disadvantaged communities.”

In other words, a well-equipped library is about literacy but also a psychological engine for enabling “disadvantaged children” to develop the initiative and skills to succeed in a competitive educational system. National Libraries and Information System (Nalis) chairman Neil Parsanlal, added: “It is our hope at Nalis that public libraries will also dispel the notion and myth, particularly amongst our young black male population, that reading and learning are luxuries that they can ill afford at this time.”

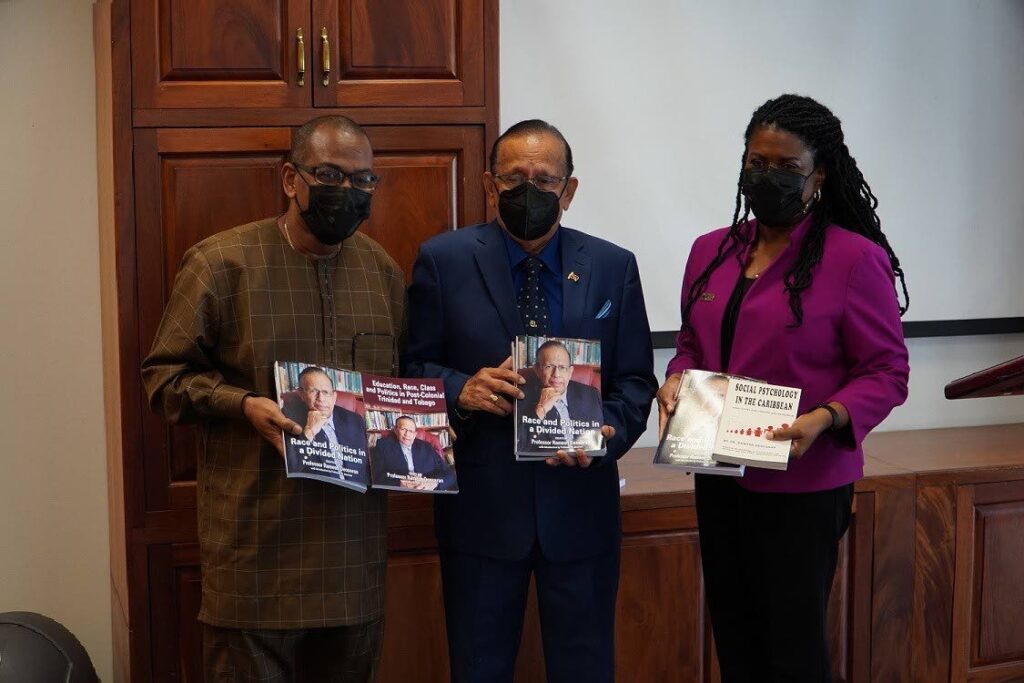

A lot of hope has been placed on this $42 million investment as a prevention instrument against crime by our “young black males.” Hopefully, Mr Parsanlal’s encouragement would bear fruit sooner than later. Last May, when, encouraged by Mr Parsanlal, I donated 100 of my books to Nalis. I then said: “I donate these books to Nalis and our three universities for three main reasons: To help cultivate an intellectual climate and reading culture in the present generation; to build a local store of data and ideas to help promote our democratic way of life; references for the next generation about today’s personalities, issues and events.”

Since the 1960’s, literacy and crime by our “black youths” have become of increasing concern. Numerous youth development and career guidance programmes were implemented to help stem the rising tide. Results remain questionable. One of the foundation youth-crime drivers has been illiteracy – the frustration to cope with social and educational challenges. Notably, the formal education system has been unable to bring effective relief and so the “little black boy” became a subject of serious sociological and educational concern.

Hence, Mayaro-born calypsonian Winston “Gypsy” Peters' song Little Black Boy, in 1997. winning the calypso crown. Gypsy sang: “There was a little black boy, a black boy was he/ The boy went to school and he came out duncee/ He never learn how to read, he never learn about math/He never learn how to write, he never study ‘bout dat.”

Gypsy continued: “All he study was his sneakers, his sneakers and the clothes he wore/ So he learning how to dress and he learn how to pose/Now he can’t get no work, he can’t get no job/ So he decide to steal and he decide to rob/But little black boy couldn’t last long at all/ The police put a bullet though his duncee-head skull.” Years after, Gypsy said “nothing has changed.” So too with Black Stalin’s many empowering songs.

Of course, Gypsy regretted the consequent controversy, especially on the charge of “racial stereotyping.” But stereotyping, triggering emotions, helps a calypso win contests. There was Weston “Cro Cro” Rawlins singing the very provocative “Corruption in Common Entrance” in which he put an entirely different spin on the failure of “black students.” Seeing it as social class and ethnic discrimination and calling a variety of “high class” East Indian and other ethnic names, he sang: “Too much high class in the de class, tra la la la la/Only high class in the de class, tra la la la la la/Too much high class in the class, tra la la la la/ Cause it looks like a class from South Africa.”

The uproar by East Indians was unprecedented. East Indians were publicly advised to stop attending calypso shows. And many did. These brief examples help illustrate the continued sensitivities about race, values and perceived discrimination within the unsettled education system.

The competitive education system is the cradle for social class stratification and as such, the subject for persistent educational and political controversies. Hence today’s struggle between the Ministry of Education, the Teaching Service Commission, the denominational boards and the Concordat. With the Constitution and politics inevitably involved, such tensions are not likely to decrease any time soon. Meanwhile, as we continue to read current demographics on crime, there is hope that many more “little black boys” will use our libraries “for a better life” as Mr Parsanlal advised. Will they?

Comments

"Reading and our black youths"