5 considerations for urban revitalisation

A vibrant, thriving, and revitalised city is one where there is near constant pedestrian activity in the public realm – that is, the streets, squares, parks, and other spaces that are open to use by all members of society; not one where everyone is shuttled from building to building.

There are five key considerations for successful revitalisation that we likely have not addressed sufficiently, and in a co-ordinated way, in our previous planning efforts:

Public engagement

Partnering with neighbourhoods has proven crucial to the successful conceptualisation and implementation of development plans in democratic societies.

Professionals and politicians are often under the impression that the general public doesn’t quite understand what it takes to achieve optimal planning outcomes. However, it is our job to devise the best ways to inform and educate on how best-practice planning is integral to addressing everyday concerns like crime, traffic, unemployment, environmental quality and more.

While there is much that we professionals do know, there is also a lot that we don’t; local peculiarities and challenges are well-understood and easily identified by community members.

Early engagement and true participatory planning can help build visions that communities feel a sense of attachment to and ones are better able to transcend the vagaries of political regime change.

Public spaces

In many plans, we tend to forget that the State’s primary responsibility is not to construct flashy buildings, but rather to develop the civic realm. In any case, for the most part, it’s not buildings themselves that are important, but whether or not they enhance or detract from the aesthetics, functionality, and activity in the public realm.

Government investments should focus primarily on ensuring welcoming, safe, functional, and comfortable public spaces; a transportation network and system that allow for good mobility for pedestrians, bicyclists, and drivers; and an environment where hazards, such as flooding, are minimised.

Despite the common tendency to oversize, public spaces that are more intimately-scaled and enclosed, by the streetwall, are typically what humans find more appealing.

Streetwall architecture

In more simple terms, buildings are primarily what give definition to the spaces that make up the public realm. A streetwall is created when buildings are set close to or at the sidewalk and occupy most or all of the sidewalk frontage of the lot of land. This according to Frederick and Mehta, and many other urban designers, “lends the space of the street a consistent shape and places ground floor uses close to pedestrians.”

Object buildings are surrounded by open spaces and inherently stand out as being distinct from the wider urban scene. They are set back from the streetwall, elevated above the level of the sidewalk, and/or rotated from the surrounded structures. This can be useful for major civic buildings, but decreases the cohesiveness and vibrancy of the urban experience when employed frequently.

Any guess how we tend to design buildings locally today, and the types of buildings mostly envisioned in the architectural renderings found in many of our previous revitalisation plans?

Zoning code

In many plans, the designers dream up grandiose development schemes, where they may even envision many of the necessary components such as appropriately high residential densities and mixed land uses. Unfortunately, they fail to address the actual rules and regulations governing land development, and therefore the feasibility that a private developer or landowner is actually able to build what is intended in the plan.

There must be a deep analysis of zoning regulations, to determine if the scale, nature, and design of development envisioned are actually in keeping with the zoning code, and if the code allows for development that is economically feasible. If not, the code needs to be amended or overhauled, otherwise there’ll be little or none of the private development necessary for the vision to materialise.

Strategy

The plan should present a number of enabling incentives for private developers, where needed, and projects, from small to grand. The goal should be to prioritise those projects that can do the most to improve the public realm.

For example: an appropriately designed building on a strategically-located lot that can reinforce the streetwall, where a gap exists, in an otherwise attractive and people-friendly streetscape; low-cost street trees that can enhance the aesthetics and allure of the surroundings and improve pedestrian-friendliness; a well-planned and functional bus or rail system that can allow for increased mobility of non-automobile users and reduce the need for driving and parking, congestion, and air pollution; and streetscape elements like bioswales that can capture surface water runoff and reduce flooding.

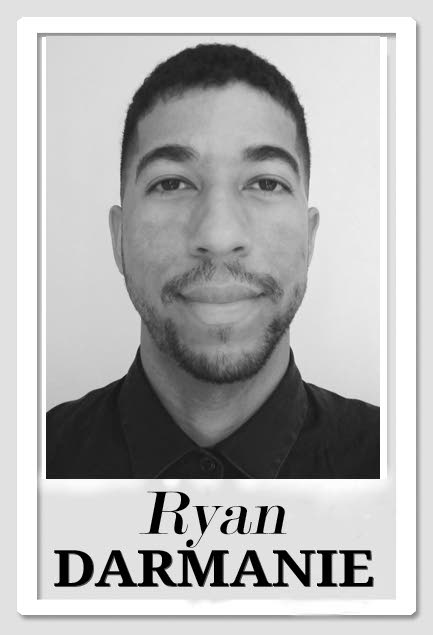

Ryan Darmanie is an urban planning and design consultant with a master’s degree in city and regional planning from Rutgers University, New Jersey, and a keen interest in urban revitalisation. You can connect with him at darmanieplanningdesign.com or e-mail him at ryan@darmanieplanningdesign.com

Comments

"5 considerations for urban revitalisation"