An appreciation of Roy Cape

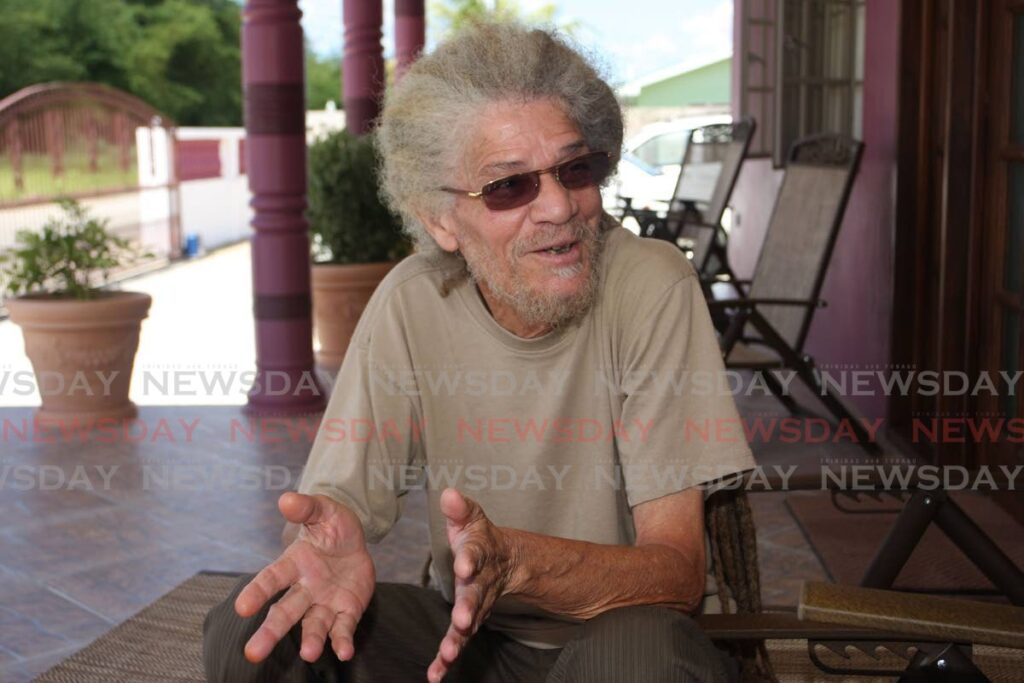

EDDY GRANT is a Guyana-born, world-renowned musician and businessman who has had numerous hits, such as Electric Avenue and Do You Feel My Love.

He has had longstanding relationships with TT and Caribbean musicians around the globe.

Here Grant pays tribute to the late Roy Cape, whom he revered for his professionalism and his respect for Caribbean music and musicians.

Cape died on September 5.

The following tribute was posted on Grant's Facebook page.

No one comes from Nowhere. Meaning that likewise, everyone comes from Somewhere. This indicates that with the person, comes not only skin, flesh, bones but all the other material that enables the human person to stand as an effigy in our world. We are also given genetic, geographical and cultural location. Who you are is a weird mixture of these. All of them good and bad, as much as there are such definitions in truth.

I have been moved to write this appreciation for many reasons, as I have been taught that we should never let a great spirit pass without we, the people whom that spirit served, making a great noise to the Universe. We should cry out to our maker that the Book of Life should be checked, to make sure that there hasn’t been a mistake of gargantuan proportions.

It is why traditionally we cry, and in particular in the old cultures. To stifle that cry from the navel of oneself is to deny the truth of one’s birth and consciousness, of having been transported into another dimension. No wonder there is so much confusion in the world, as we’ve sought to follow others into the world of painless birth.

I hold to a theory that the pain of coming into this world is equal to the pain felt at our transition, from this temporary state and dimension. As we’ve grown more and more like other people, their cultures, and their habits, we have sought to sanitise ourselves. We have been convinced not to make so much noise, as though that noise will bother some arbiter of taste.

What’s taste got to do with anything? Our grief mechanism has been seriously messed with, as we have been genetically modified here in the African diaspora, all of us.

This brings me to my brother-in-arms Roy Francis “Roystan” “Pappy” Cape.

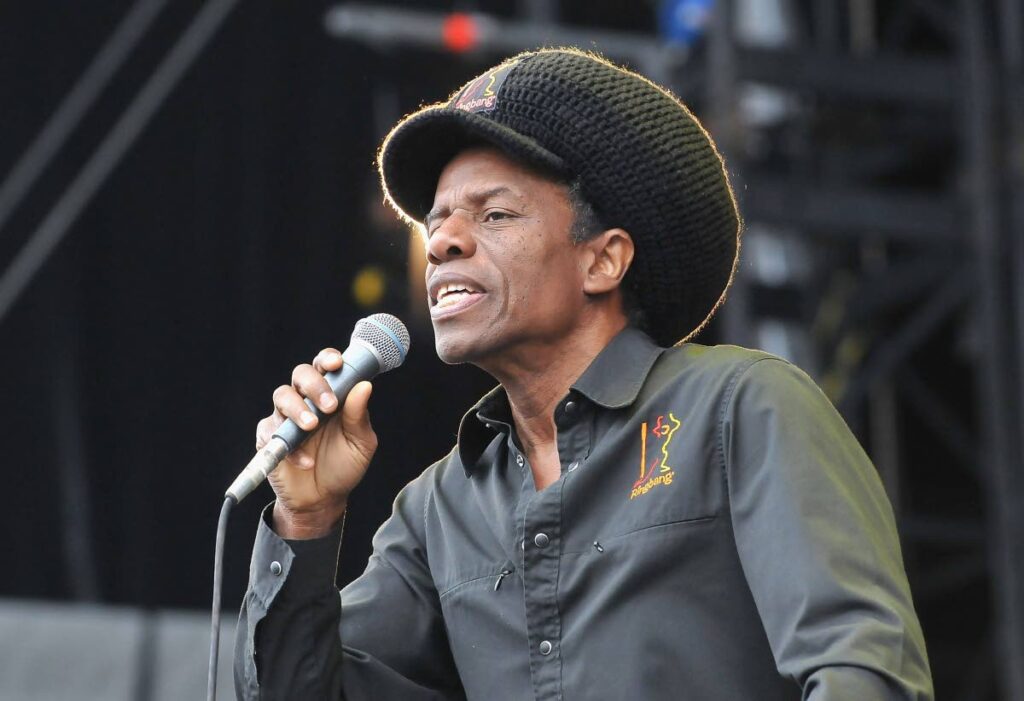

Now, in this time in the world of music, you can almost not call Roy’s name without mentioning the name of Leroy Calliste, Black Stalin. These two people, though so different in their hue, were, for much of their lives, musically, culturally, and ideologically, like twins, like salt and pepper.

To hurt one was to incur the wrath of the other. True brothers. My admiration for their brotherhood knows no bounds, especially in a country where competition reigns supreme and traditionally, it was only about who is king for a few days in a year, and where traditionally, calypsonians had no respect for musicians, and likewise, musicians had little respect for calypsonians. There must be a serious paper to be written on this relationship, alongside that of Roaring Lion and Atilla the Hun, two of the greatest of all time.

What is signal in the case of Roy and Leroy is their manifest dedication to Trinidad and Tobago. They were unshakeable and seriously dedicated to the fight, the struggle for recognition of the African voice in political affairs at home, in Africa, and its diaspora, without seeking to disrespect, dispossess or denigrate any of the other races, either in TT or elsewhere.

Roy had an incisive vision when it came to the music he played behind the calypsonians. He knew their tempo and their temperament, which enabled him to be the perfect intermediary in all matters, both musical and personal.

I would be somewhat of a hypocrite if I failed to acknowledge that though he gave 100 per cent to calypsonians, which was 50 per cent more than they could get from any other band, the two who got his “maw,” as they would say in my little village, Plaisance in Guyana, would be the Mighty Sparrow and the iridescent Black Stalin. This is not idle hearsay or bacchanal, but what I’ve witnessed time after time.

One particular time I happened to be in Trinidad to sign the Mighty Sparrow’s recording and publishing contracts. Sparrow was due to play at the Naparima Bowl, down south, and I was invited, with my assistant, to the gig. Sparrow had just arrived backstage to great acclaim, as his new song Both of Them had just been released and heralded his great comeback; he had not been seen since his song Doh Back Back. The people in South Trinidad were ready for him.

This put Roy in a funny position that night, having to stand between these two performing geniuses. The audience was hot to trot, and as usual, the bacchanal started backstage about who would come out best that night. The "negrogram" was saying that Roy was going to sacrifice Sparrow in favour of Stalin, but NOOO!

Even Stalin said: “Edworrrd, da is de boss out dere, boy, and Roy putting reaaal fiyah in he tail. Da is a reaaal professional out dere, boy, da is Roy Cape.”

We’re dealing with one of the classiest roots musicians in the world. Certainly in the Caribbean, and especially in TT, where musicians found it hard to be recognised, especially outside of the Carnival season. You were a papier-mache king at Carnival time, but at least that was something.

The rest of the year, can you imagine what it was like? Carrying a band the size of the Roy Cape Kaiso All Stars? It was hell.

But as I’ve told you, Roy Cape was no ordinary bandleader. He always reminded me of Quincy Jones, when, as a young man, Quincy showed his cojones by taking a full orchestra of seasoned professional jazzmen to tour Europe and ended up in France, broke. So much so that he had to sell all his song copyrights just in order to pay his troupe’s – which included the players’ wives – and the orchestra’s passage back to the good old USA.

That’s Roy Cape, a man with serious testicular fortitude. He would starve, and I’m sure his dear wife could attest to more than that, before putting his band in that position. I know; we sat under the historic Hanging Tree at Bayleys Plantation and spoke of many, many things, both music, our musical history, and personal fears, none of it out of line with the trials and tribulations of a leader.

Roy loved and respected those who came before him, but especially the venerated Frankie Francis, who like himself, was both a “clear-skinned black man” and an alto-sax wizard. It was Roy who pointed him out to me and caused me to donate the prize awarded to Frankie by Makandal Daaga at one of the NJAC award shows. It was my deepest honour that night, as Frankie, whose playing I worshipped as a precocious young child in Guyana, was nearing the end of his playing days.

I became a friend of the NJAC and Makandal Daaga, the leader of the organisation, and attended their events whenever I happened to be in Trinidad, which was quite often. Roy knew, almost by some kind of osmosis, how dedicated I was in my thrust to have the music of my ancestry preserved by Caribbean people – any one of us – and we bonded over a very short period of time. All the Old Brigade showed appreciation for his love, professionalism and respect for what they had done in their time. For him to get that respect from them was important and he always spoke in his genuine, reverential manner, of what is known today as classic calypso, when we would discuss the true lineage.

Having been steeped in the classic calypso of the old stagers, he had no problem attuning himself to what became soca without taking sides in what became almost a media frenzy around the subject between Lord Shorty and my good self. As a matter of chronology and history, Roy was present at Bluewave Recording Studios when I was invited by Dr Vijay Ramlal to speak on the subject The True History of Soca, when he was about to relaunch his version of the Soca Monarch Competition.

I was working on Black Stalin’s album Rebellion and the introduction of yet another genre, named ringbang, and had asked Roy if he thought Stalin would come along with me to help, and he’d said: “Why don’t you speak to Stalin?”

He felt that once it represented our Caribbean culture, Stalin would be positive. So said, so done. Stalin’s answer is unequivocal and emblazoned on Rebellion, where he sang ringbang with the Mighty Gabby on Santimanitay, and he was also the first artist to issue forth the word ringbang, in his song All Saints Road. By the end of that Carnival season, ringbang, as a musical force, had established itself in Barbados, TT and the wider Caribbean, with Roy Cape’s Calypso All Stars pushing the new sound of the Caribbean, and there was even more confusion.

Roy would have none of the prejudice, as talk of a “Bajan invasion” ensued. He just kept on playing the groove because the people loved it.

Eventually, sheer political force would make even the Bajan artists, who had become extremely popular in TT, see fit to announce to anyone who would listen that what they were playing was soca, not knowing their history of Caribbean music and my place in it.

Time would come when I’d be vindicated of all the nonsense bacchanal, but Roy Cape, with his ever-present even hand, would come out to the TT media in open defiance on my behalf. A plethora of others would follow, but that first leap of faith belonged to Roy Francis “Roystan” “Pappy” Cape, my brother eternal in humanity and music.

Roy Francis Cape’s memory will live on.

To his wife and extensive family, his friends, fans and well-wishers, I offer the most sincere condolences on behalf of my wife, my children and my staff, all of whom knew and loved and respected the man Roy Cape.

Ringbang for life.

Reprinted with permission from Eddy Grant

Comments

"An appreciation of Roy Cape"