Hurt without shape

ANU LAKHAN reflects on A Literary Friendship: Selected Notes on the Kamau Brathwaite, Gordon Rohlehr Correspondence, by Gordon Rohlehr. (Peepal Tree Press, 2024).

Let’s begin at the end, shall we?

Taken from Notebook No 19 of Gordon, Words Need Love Too, 2016: “I have, over five decades and counting, written at length on the work of our poets, calypsonians, novelists and even historians, imposing on my meagre public the burden of reading long, arduous things; of rolling boulder after boulder of hard words; trying to lift these, my fellow verbalists, out of their solitude, by giving to their words the love they desperately need. I have tried to clarify hard, knotted obscurities, to work through, rather than around entanglements of word or metaphor.”

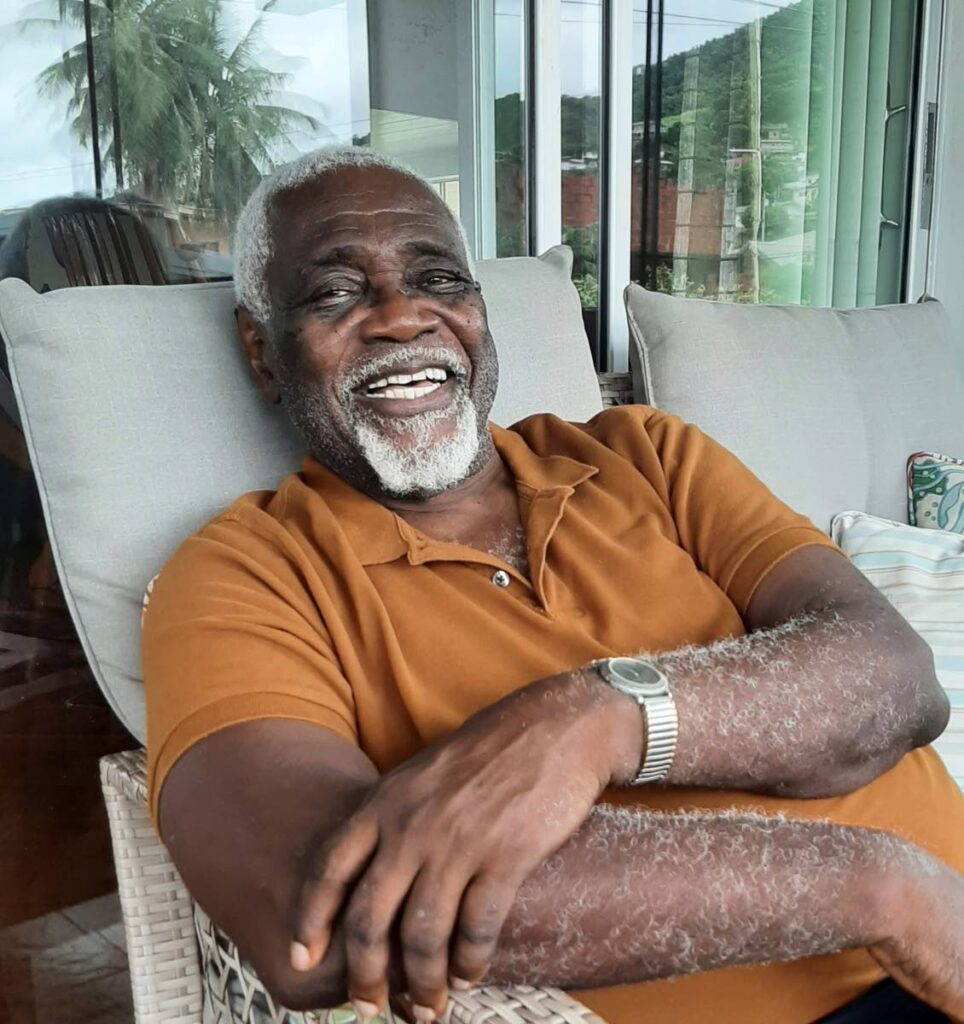

These are his words, but this is also Gordon as we know him in every way: the writer, critic, academic, teacher and friend.

This book is not for those afraid of the end. For those afraid of failure, erasure, shunting, shunning, or frailty. Not for those who are afraid of being a little afraid of what they might see of themselves in and around the words and episodes.

Here is what you already know: this is a story of two of the more extraordinary minds we will see in our lifetime – and not only in or of the Caribbean. Just in our lifetimes. Everything we do need not be prefaced by “in the Caribbean,” or “in the West Indies,” or “in Trinidad and Tobago” as though such caveats are essential for some containment or cordoning-off of what we produce.

To locate ourselves is one matter. To restrict, quite another.

But – as I was saying – here are two minds, both curious and curiouser; both creative, both searching, articulate and ceaselessly gathering whole libraries of knowledge they wanted to share. Both knowing that words need love. How much were they allowed to do that? How many classrooms, conferences or publications would have been enough?

One had more opportunities and recognition than the other. As both this text – as well as others – and as readers of both men are aware, it was no mean part of Gordon’s life’s work to promote and demystify Brathwaite’s writing and secure his place in the canon.

Kamau wrote. And he wrote and then he wrote some more.

In what he writes to Gordon, there is a never-endingness to his sense of isolation and despair. The feeling that he is ignored, misunderstood and undefended. Since what we have here are his letters and Gordon’s commentary, it is a marvel there is space to think of these concepts as applying to a wider audience, because Kamau does not seem to leave room for any thoughts beyond his own person.

There is a humility and nobility in both the work and the persona of Gordon Rohlehr. There must be – inherently, intravenously, involuntarily even – to allow him to do the work he did and kept doing and not just for Brathwaite and other vaunted writers.

He did it for an ocean of students – fresh waves every year – from St Augustine to darkest Nagadoches, that “one-hoss town,” where he once tried to teach a course in calypso. Four students signed up. They deregistered on the first day.

I’m lifting this bit from its context, but its relevance is not lost, he writes: “It was like me asking my own students at St Augustine ‘Who was Uriah Butler?’ No one knew except one girl, an exchange student who had been prepped, but who subsequently died, probably under the weight of such strange and unusual knowledge.”

How did Gordon survive us?

He was the Bookman, but one of grace and generosity. A Bookman from whom we did not fear eternal damnation, but from whom we knew we would always learn, and lean on.

In one exchange, Brathwaite goes to the Rohlehr memory bank for items like: the connection between Derek Walcott and VS Naipaul; a production by the Trinidad Theatre Workshop; better understanding of Eric Williams and CLR James; Pat Bishop’s thesis; Ken Ramchand’s date of birth and the title of his thesis; Gordon’s own articles and books of kaiso.

Brathwaite is not alone here. I think many of us thought Gordon would always have information we needed, even Ken’s date of birth.

Gordon is known so much for what he taught us, but there is not nearly enough discussion of the quality of his own writing.

This is one of the most damning oversights on the part of those who seek to address his work. Because, as with all writing of quality, it is often in the phrasing and parsing itself that we come to some of his most important insights. Because you, the reader, are so caught up in the one idea you think you’re following, you miss myriad connections, allusions and nods in the general direction of god-knows-what-else.

There’s something that haunts me. He’s talking about Don Drummond, rhapsodising, really: he says, “The trombone could howl in the middle of some sentimental curve of song. Drummond had a habit of leaning, just that little bit longer, just that little bit more heavily, on a note, and in doing so he’d define what that moment meant, giving it meaning, point.”

That’s not a fine piece of writing about music. It’s a fine piece of writing, period.

I also see so much of Gordon in it and perhaps that is the ghost in the sentence. Because that is how he wrote and how he spoke. By knowing where to lay stress and emphasis on theme or character or, indeed, writer, he gave meaning.

Think of the great sprawling mural that is the body of work he has left. It is a grand thing to stand back and take in.

But then start looking at it sentence by sentence, one idea linked to another, one square inch of Rohlehrian thinking at a time, and there you will find the thing that has been his trademark from his earliest work to the present: the ability to find connections across centuries and continents of text. Not to ignore history, but to draw it closer by revealing patterns. To show the seamlessness of lives. And to do all this not in an alienating academic way, but an accessible, inviting style. He wanted to share.

During an especially difficult time in his life, he says a pessimism had always nestled at the centre of his void. And I cannot doubt it. Not that the enthusiasm, wit, humour and insight that we saw as his everyday dress was a mask or a mas, but you simply cannot ignore the death by a thousand slights.

Love is a killing thing. And Gordon loved us and what he did. He made brave choices about – among other things – where to be, what to teach and how to publish. These words are not in the text, but we do not read only for words, but also for spaces. Being here meant that the world of opportunities available to those who went foreign were not his for the asking.

His passion for calypso, soca and all their family and friends didn’t seem to resonate with students a hundred years ago when I was on campus. The beautiful, important scholarship on these subjects: who is studying it? Who is engaging with it, apart from the odd demented writer who forces it weekly upon innocent readers?

There is work being done on our music, but it’s liming outside the region, somewhere in the vast academisphere. We complain about this, but then we keep ignoring it. The idea that your ideas will be forgotten is piling up around you.

Of Musings, Mazes, Muses, Margins, he says “Betty (his wife) is against my publishing what she reads as a mad production of a man with multiple personality disorder, whose other books are not selling and take up too much space in the house.”

Just like at the conference to mark his retirement, at which everyone who spoke about Gordon thanked Betty, even now we are indebted to her. Hers is the unmentioned but devoted friendship that runs through the book.

This literary friendship is a fine thing, a fine idea, but if it doesn’t cut both ways, it only cuts. When Gordon invites Kamau to his retirement affair, Kamau says yes, he says no, yes, no, yes, no. Then, Gordon writes: “We waited for two hours at the airport only to discover that his name was not on the list of BWIA passengers.

Friendships, I’ve always believed, might well be the most important relationships in our lives. They are almost the only ones we get to choose.

I have given myself latitude to be grim and morose because I am grim and morose. But also because when you read this book, I do not want you to gloss over the pain. That is what we do every day. And no good comes of it.

Comments

"Hurt without shape"