Novel Integrity Commission case

THERE is nothing unfamiliar about recent complaints relating to the Integrity Commission (IC), whether from politicians who feel harried and prosecuted by its requirements or commission officials who want more powers.

Yet, the court action announced by the constitutional body this week over the extent of its funding by the Government is an entirely novel development altogether.

Just when you thought there was nothing new under the sun in relation to this long-beleaguered, oft-dysfunctional entity that has been at the centre of scandal from time immemorial, a group of lawyers has asked for judicial clarification over the State’s duty to provide it with money.

If the Supreme Court takes up the case – and there is no indication it might not – the implications of a ruling would be far-reaching. At stake here is not just the functioning of the commission but every nominally independent entity established under the Constitution which relies on state funding, from the Parliament to the Elections and Boundaries Commission.

“The State is under a statutory obligation to provide the Commission with adequate human resources,” the IC asserted in a statement issued this week. It cited an unreleased opinion from the Solicitor General on the nature of the State’s purported obligation to provide “adequate financial support.”

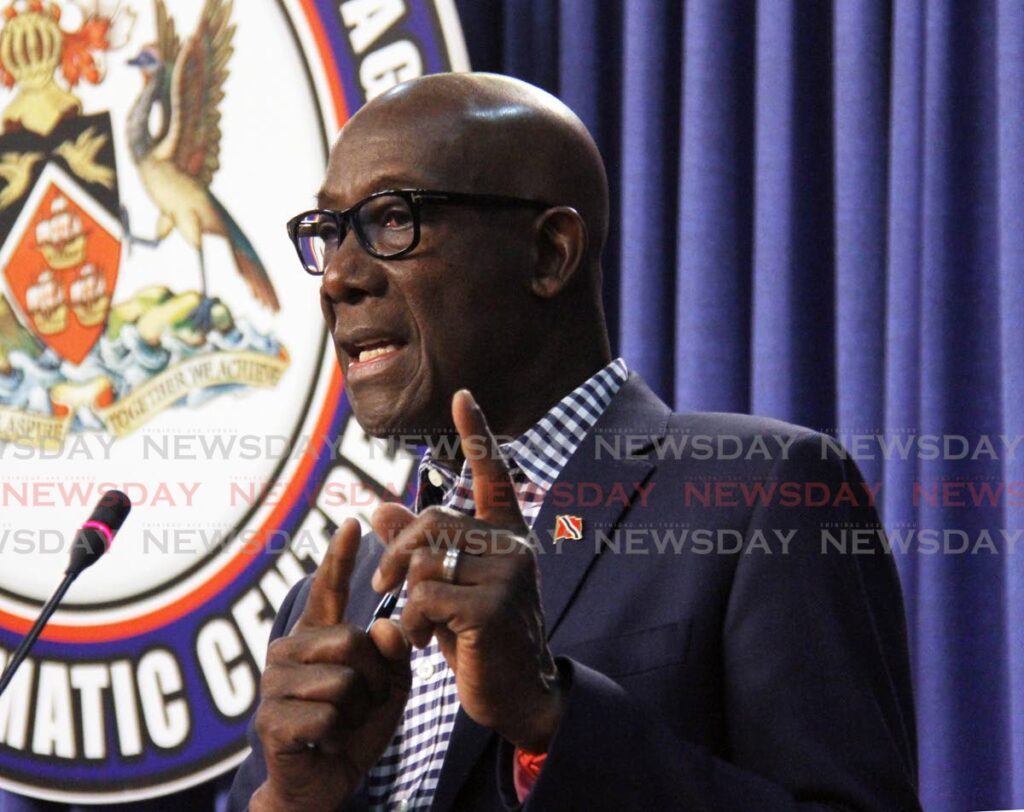

In an immediate response which reveals the extent of the breakdown in the ordinary course of things, the Prime Minister, on Tuesday retorted, “Maybe the issue is far too many ill-advised and politically motivated investigations.”

Dr Rowley has a long history with this body. It was on the part of a previous commission that brought his plight under the Patrick Manning administration into sharper focus.

That commission, infamously, was in communication with Mr Manning over Landate allegations. The 2009 High Court ruling of Justice Maureen Rajnauth-Lee, which awarded the Diego Martin West MP thousands in damages, is a study of both the nature of unfairness and executive overreach.

In more recent times, the PM has bristled at activity by the latest commission, the 17th, in a manner that suggests he will not forgive and forget.

But Prof Rajendra Ramlogan’s commission, too, has a long memory. Its case seems predicated on a pattern of funding being reduced when compared with previous years. Allocations have gone from $83.5 million in 2012-2014 to $25.7 million in 2021-2023.

While the body implies this court matter will not incur a cost because it is being done pro bono by lawyers, if the State joins as a party and if it is appealed, thousands will have to be spent.

On the flip side, if there is a judicial determination that no government can deprive an independent body of needed funds, there could be a bolstering of all such institutions and a commensurate transformation of public life.

Comments

"Novel Integrity Commission case"