Making up for lost years

No one ever expected them to succeed. Many people were sure they would end up back behind bars.

Sunday Newsday tracks the progress of eight men who won their cases or got out on bail. Their lives outside prison are featured in a series on inmates from Debbie Jacob’s CXC English classes and debate teams.

Why did these men make it when so many others failed?

Read their stories of redemption, rehabilitation and reinvention in the Sunday Newsday.

VIII

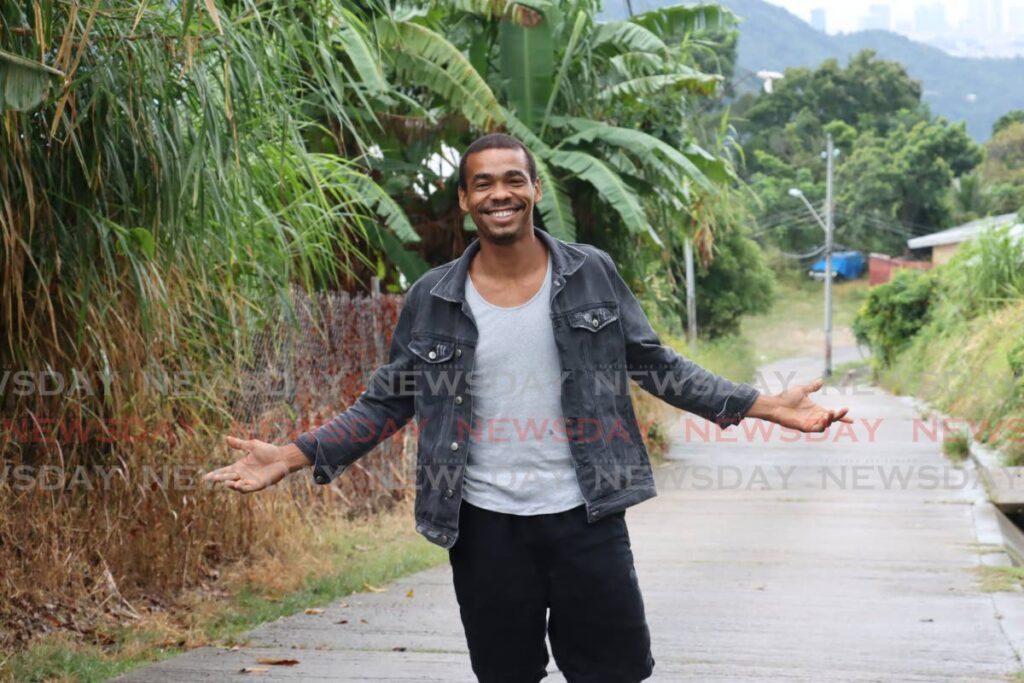

In Port of Spain Prison, Mikado Toussaint always had a notebook in his hand. His constant smile served as a mask to hide the frustration of being in prison.

On December 15, 2022, Toussaint, 24 when he entered prison, won his case, after spending 11 years and five months in remand.

The verdict of not guilty did not bring the joy he imagined.

“As soon as I came out of prison, they tried to kill me, but killed my father instead,” he said, in a voice that sounds casually accepting.

In the culture of violence that surrounds many young men, death is a given.

On January 11, Toussaint said, he went into the bush for two weeks of reflection, stayed by himself and talked to the Lord.

“God said, ‘Continue what you’re doing. Do good things.’”

He felt he got the answers he needed to move forward with his life. With his ever-present smile, he plunged into helping his family.

Toussaint does woodworking, fixes up relatives’ houses and “...lives a life like I was never in there.”

He can’t bring himself to say “prison,” and he can’t completely shed the memories of years lost because of testimony from someone who claimed to have seen him at the scene of the crime. (The witness later changed the original story.)

“Sometimes I forget I am not in there, and catch myself hiding my phone. When I hear keys in a lock, I tense up,” said Toussaint.

Keeping busy helps him cope. He is rebuilding the steps of his mother’s house, and putting in dropped ceilings.

“I am always busy. I wake up and think about the things I will set out to do. In the morning I say exactly what I’m doing for the whole day. Even if I say I’m rocking back, that’s what I will do. I keep my word.”

He depends on no one, and is taking charge of his life.

“To get a job is a real pain. They want job letters and things you can’t get after being in prison for so long.

"I’m lucky. I have woodworking and joinery. In prison, I got a certificate from the Wishing for Wings Foundation’s PVC furniture-making and decorative tiling classes.

"I have a certificate for the peace and meditation classes. I use everything I learned.”

Toussaint plans to go into agriculture full time, to grow basil and thyme, citrus, ochro and peppers on the land his father owned. He always enjoyed being in nature and that part of his life has been his greatest joy to resume.

“I appreciate going to the beach, hiking and scuba diving – the same things I always enjoyed. I love walking barefoot.”

He sometimes leads people on challenging hikes.

“We hiked a trail going over Paramin into Diego Martin.

"I have an uncle who is a natural herbalist, so I offered people who signed up a hike and tea. My uncle brought herbal tea for people to drink at the end of the hike. Many people don’t know about mountain roads, or the bush right there in their yard that is good for them to drink.”

Before he went to prison, Toussaint worked with a search-and-rescue team.

“That work gave me knowledge of the North Coast hills. I want to rehabilitate all those old trails. If you say 'lime and drink,' people know that, but they don’t know how to find the beauty in these old trails.

“That work gave me knowledge of the North Coast hills. I want to rehabilitate all those old trails. If you say 'lime and drink,' people know that, but they don’t know how to find the beauty in these old trails.

“Middle-aged and elderly people are more aware of nature, so I would like to introduce these indigenous trails to students so they can build camaraderie.”

Bit by bit, Toussaint said he’s fitting back into society.

“It’s just that people shun me who know I was in prison.”

He paused when he finally said the word “prison.”

Smiling, Toussaint picked up a rock he found recently while scuba diving.

“I thought it was a piece of gold,” he laughed.

He spends as much time in nature as he can.

“I don’t like being inside a house. It makes me feel like I’m still locked up. Sometimes I take my hammock in the backyard and sleep outside where I can see the stars.”

Toussaint said he’s never going back to prison. Vigorously shaking his head, he said, “No way. I wake up these mornings with fresh air – no urine on the floor, no officer shouting. When my mom shouts, I tell her, ‘Mom, you could talk a little softer than that. Talk a little gentle.’

"She says, ‘That’s how I talk,’ and I say, ‘Remember, I was in a rough place.’”

In prison, Toussaint jotted down his thoughts and wrote essays and poems – mostly romantic ones. He was a dreamy student and a debater on the first prison debate team, formed in CXC English class.

At home now, he hides his notebook under a couch.

“If my mom finds it, she will read it,” he laughed.

He reads a poem he has recently written.

"The day my life started over it was like jumping off a waterfall and passing the droplets on the way down…

"To good nights and into wonderful mornings with the sweetest and most amazing woman in the world getting up next to me.

"What a life to live.

"It's full of everything.

"You ever see or feel like a love movie or a love song that you dance to every minute?

"Moving on in life from your past is not easy.

"You have to make things happen.

"You have to want life and understand what life has to offer you.

"You must make the best out of it. Time stops for no one so make the best out of every moment."

Toussaint, now 37, said he is writing a book about his life, called The Place of Iron and Steel.

“But right now, I have to go down the road to get some nails to finish these steps before the concrete sets.”

Briskly, Toussaint walked to the door. There, he paused and spun around. Framing a closeup of his face in a FaceTime call, he beamed broadly and said, “Trinidad is a real beautiful place.”

Comments

"Making up for lost years"