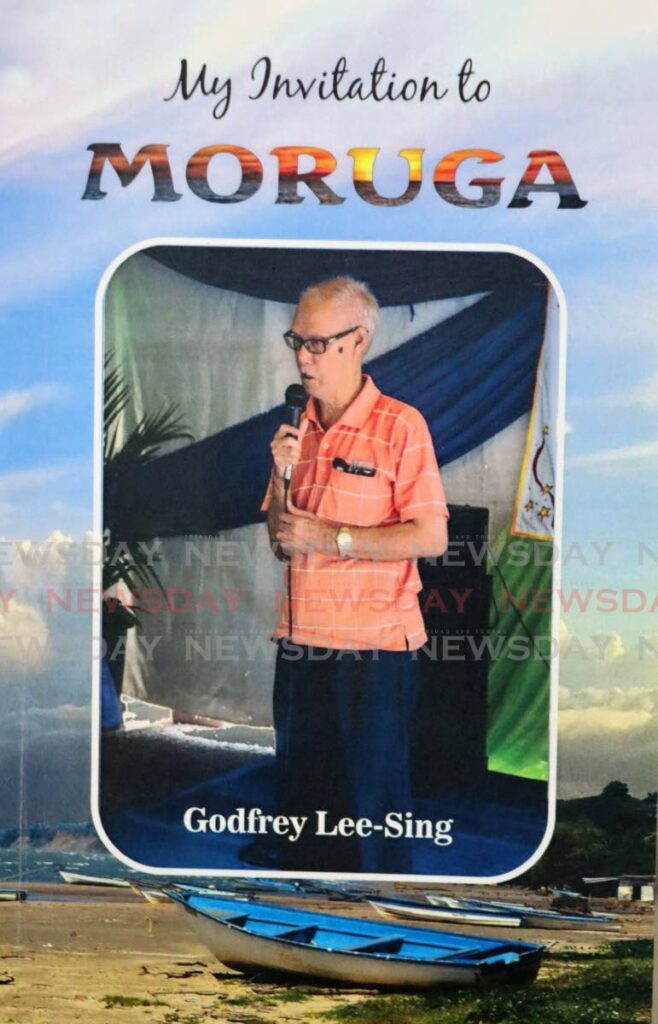

Godfrey Lee-Sing documents life of Chinese in Moruga

VETERAN politician and community activist Godfrey Lee-Sing shares his insights into the struggles and joys of rural life in Trinidad in far-flung Grand Chemin, Moruga, in a reader-friendly personal memoir, My Invitation to Moruga.

Less than 100 pages long, including a dozen pages of photos of family members, personal mementos and local landmarks, the book is not intimidating, but can be read in a relaxed weekend.

It provides a series of snapshots of stages of Lee-Sing’s life in Moruga, a town probably retaining the flavours of life once prevalent in villages across TT.

It can contribute with other books to building a jigsaw-puzzle-like picture lifestyles, routines, life patterns, activities, values and interactions that helped shape us as a people in all our multicultural glory.

It should be read by any of us wishing to understand this society – tourist, schoolchild, journalist, politician, author.

The book is small, so it touches briefly on a range of aspects of living in Moruga. Hopefully it will encourage other individuals to tell their life experiences in written form, to preserve them for the present and posterity.

The first chapter, My Early Years, might evoke in the reader recollections of VS Naipaul’s Miguel Street and Sam Selvon’s A Brighter Sun.

Although Lee-Sing has not sought to write a novel to compete with Naipaul’s engaging Titus Hoyte or Selvon’s Tiger, his account of family life in Moruga helps document the story of us, and could inspire short stories, say centred on the life of a fictitious Chinese shopkeeper in rural Trinidad.

What is perhaps most striking about chapter one was how hardworking his parents were, even against the privations of rural life such as poor water supply and roads spelt out later in the book.

Lee Wah John, Lee-Sing’s paternal grandfather, left China in 1911 in the wake of the Chinese Revolution, worked under harsh conditions to build the Canadian Pacific Railway, returned to Guangdong in China, went to work on sugar estates in Cuba, returned to China, and then settled in Trinidad.

“Prospects and opportunities on the island were favourable compared to the hardships created by the revolution of 1911,” the book relates.

“Grand Chemin was home to a Chinese community, one connected by kinship and friendship, whose members had established businesses like shops and bakeries.”

They could welcome a new migrant and help him settle in and adjust to his new life.

Lee Wah John hired a villager, Mrs Coward, to teach his family English, the key to assimilation for a migrant to TT.

Lee-Sing’s maternal grandfather, John Akin Thong, also came from Guandong, worked in Canada and in Cuba, and ended up in Trinidad, where he married an East Indian woman and moved to Grand Chemin.

Lee Wah John’s children included Alexander, who married John Akin Thong’s daughter Iris, who then had children, including Lee-Sing.

Alexander and Iris owned a general shop with an adjoining rum shop, a building for packaging cocoa and coffee beans, a bakery and two fishing boats.

“Theirs was the classic immigrant story of survival and success through hard work and commitment to family.

“They toiled long hours, seven days a week, raising their children and tending to their businesses.”

Lee-Sing recalls Alexander as “an industrious and cheerful man who loved cooking and singing.”

Alexander would quarrel with local fishermen who were discarding eels and crapaud fish from their nets.

“’No! No! Don’t do that. Bring them for me!”

Lee-Sing says, “Nothing tasted sweeter, he claimed, than what they had just discarded.

“He knew how to convert the eels and the crapaud fish – with its dark skin and broad bulbous head – into dishes to feast on.”

Lee-Sing relates the practice of the Chinese village shopkeeper’s book of creditors, the sorry state of his parents’ book actually leading to the taxman giving them a tax write-off because of all the unpaid debts owed to them.

Giving insights from his own role helping in the family rumshop, he says, “I patiently bore witness to many of the ups and downs of life in our village.”

As time passed, Lee-Sing and the other children left Moruga to study in Port of Spain and San Fernando. Eventually, when his siblings migrated, he had to return to Moruga to help his parents to manage their shop.

Chapter 2 – Called to Serve – touches on church life in Moruga, where Lee-Sing lauds the nuns who ran things at St Vincent Ferrerr RC Church amid a shortage of priests, plus hard-working parishioner Annie Emelda Bayley-Edward.

In a section called Do You Believe in Miracles, Lee-Sing recalls a near-car crash, but in which “someone or something” unknown suddenly guided the car to safety.

Chapter 4 is his account of being the lone PNM councillor on the UNC-dominated Princes Town regional corporation.

Lee-Sing speaks about his community activism in setting up the Moruga Chess Club in chapter 5.

In chapter 6 – For the Fisher Folk – he recalls the key role of fish in Moruga life, for fisherman, fish vendor and fish consumer, but lamented the challenges in recent years of dilapidated facilities and depleted fishing stocks.

Lee-Sing, in chapter 7, touts the benefits of Moruga hill rice, brought to TT from the US by freed former slaves who had fought for Britain in its attempt to reconquer the US in the 1812-1814 war.

“The new settlers came with the bearded hill rice their ancestors had brought from West Africa to the slave plantations of the US.

“It has a distinctive red colour and a nutty flavour.”

He said the rice can boost nutrition and create hundreds of jobs.

“Moruga hill rice can be a gateway to a better future for the people of our district.”

In chapter 8, Lee-Sing recalls the former Discovery Day celebrations at Moruga, since replaced by the Emancipation Day holiday.

Chapter 9 is titled Facing the Future. He urges improving the area’s infrastructure and lamented the decline of local landmarks.

Lee-Sing says the local church was once struck by lightning, with its bell tower now in dire need of upkeep.

“The church is a national treasure and a tourist attraction.

“Any help from the Government and private sector to effect repairs would be welcome.”

He laments that the local community centre was now closed, as was the local courthouse which now has a tree growing through it; and the condition of Moruga Public Library was not conducive to learning.

He then offers prescriptions under the rubric of his Mind Your Own Business Party (MYOBP) (reachable at 656-7018), proposing “godly ideals in the execution of national policies.”

So the book comes full circle, from reviewing the past to noting the present to anticipating the future, in an unpretentious form, a work from which a variety of readers may benefit.

Comments

"Godfrey Lee-Sing documents life of Chinese in Moruga"