Hydrogen-powered aircraft: The future of aviation

One of the five strategic objectives of the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) is environmental protection.

ICAO’s key environmental goal is to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by the year 2050 in support of the Paris Climate Accords.

As of February, 195 members of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change are parties to the agreement.

Net-zero emission is defined as the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions as close as possible to zero. Any remaining emissions are re-absorbed from the atmosphere by oceans and forests.

Net zero is reached when all the carbon emissions have been eliminated as far as possible and the remaining emissions are eliminated through other mitigation methods such as tree planting and other natural forms of CO2 absorption.

The Paris Agreement's long-term temperature goal is to keep the rise in mean global temperature to well below 2.0 °C above pre-industrial levels, and preferably limit the increase to 1.5 °C recognising that this would substantially reduce the effects of climate change. Emissions should be reduced as soon as possible and reach net zero by the middle of the 21st century.

To stay below 1.5 °C of global warming, emissions need to be cut by roughly 50 per cent by 2030.

Recently, TT has been experiencing the effects of climate change by the record-breaking outside air temperatures.

According to the European Commission, the aviation sector creates 13.9 per cent of the emissions from transport, making it the second biggest source of transport emissions after road transport.

If global aviation were a country, it would rank in the top ten emitters. Someone flying from Lisbon to New York and back generates roughly the same level of emissions as the average person in the EU does by heating their home for a whole year.

ICAO’s 2022 Environmental Report, Innovation for a Green Transition, identifies renewable hydrogen as an alternative fuel that can achieve almost net-zero emissions.

The by-product of hydrogen as a fuel is water vapour.

Today, most high-altitude rockets are entirely fuelled with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen cryogenic propellants.

Liquid-fuelled rockets have higher specific impulse than solid rockets and are capable of being throttled, shut down, and restarted.

Specific impulse is a measure of how efficiently a reaction mass engine such as a rocker or jet engine creates thrust.

There is ongoing research to evaluate hydrogen as a possible aviation fuel in the future.

But, several factors hinder the possible use of hydrogen in commercial flights, such as onboard storage, safety concerns, regulatory requirements, the high cost of producing the fuel and the need for dedicated infrastructure at airports.

In support of the long-term environmental objectives for civil aviation, the two major aircraft manufacturers: Boeing and Airbus are involved in ongoing research to demonstrate the feasibility of hydrogen propulsion systems for future aircraft and to develop technical solutions to overcome any challenges such as the onboard storage of liquid hydrogen.

According to Airbus, its ambition is to bring to market the world’s first hydrogen-powered commercial aircraft by 2035.

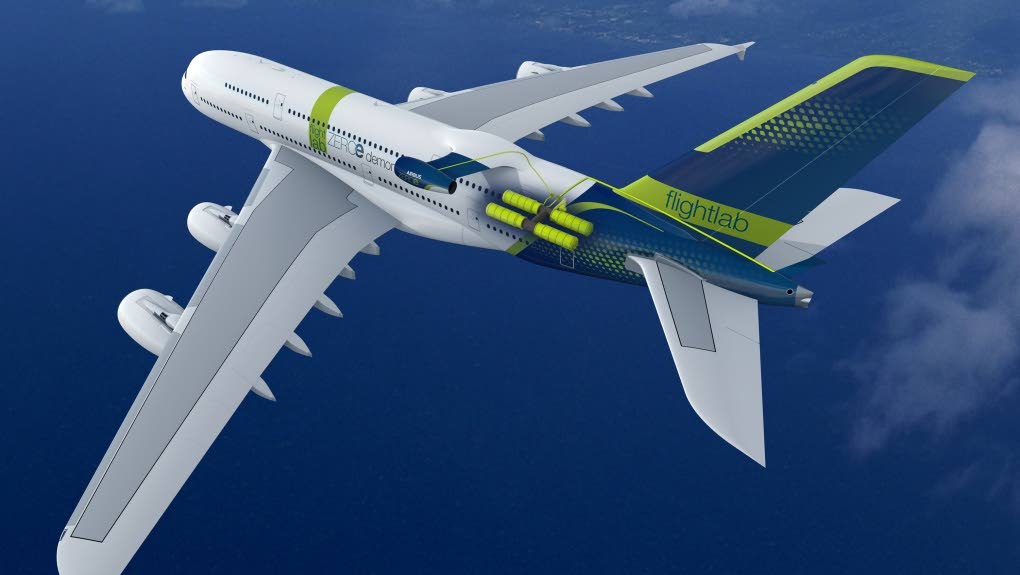

To get there, Airbus “ZEROe" project is exploring a variety of configurations and technologies, as well as preparing the ecosystem that will produce and supply the hydrogen. Many of these milestones revolve around establishing the means of propulsion, either via hybrid hydrogen-electric fuel cells or direct hydrogen combustion. Airbus test aircraft A380 Manufacturers Serial Number1 (MSN1) is taking the lead in testing these technologies that will be vital to bringing a hydrogen-powered commercial aircraft to market.

According to Airbus vice president Glenn Llewellyn, “Airbus's ambition is to take this aircraft and add a stub in between the two rear doors at the upper level. That stub will have on the end of it, a hydrogen-powered gas turbine, and inside the aircraft, there will be hydrogen storage and hydrogen distribution, which will feed this engine with hydrogen.”

Reconfiguring MSN1 will include installing four hermetically sealed liquid hydrogen tanks at the rear of MSN1’s lower main deck, plus a distribution system to feed the hybrid hydrogen engine on its mounting stub.

“There will be a huge amount of instrumentation and sensors around the hydrogen storage distribution and hydrogen engine,” Llewellyn said.

The resulting flight test data will be studied by Airbus engineers on the ground, as well as relayed to an onboard flight test station in real-time.

On the other hand, Boeing stated in its 2023 Sustainability Report that the company and the aviation industry recognise finding solutions to climate change as an urgent challenge of this time. Boeing is united in its goal to ensure that billions of passengers can continue to fly every year to connect with friends and family, discover new places and cultures, engage in commerce and care for those in need. Achieving this objective requires a portfolio of innovative solutions and partnerships that allow the aviation sector to decarbonise.

Boeing is focused on four key areas – fleet renewal, operational efficiency, renewable energy and advanced technology.

It has already developed the hydrogen-powered Phantom Eye – an unmanned aircraft system – which is a liquid hydrogen-fuelled, high-altitude and long-endurance aircraft for persistent intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance and communications missions. The demonstrator aircraft is capable of maintaining its altitude for up to four days while carrying a 450-pound payload.

In the March issue of Aerospace TechReview Boeing’s director of sustainability and future mobility, Ellen Ebner said, “The aircraft industry is in the beginning stages of creating a hydrogen-powered aircraft suitable for regional missions. Furthermore, the aircraft needs to fly economically viable missions and use economically viable green hydrogen.”

The use of hydrogen-powered aircraft will have to be carefully analysed and flight tested by regulators such as the FAA and EASA before such aircraft are allowed to enter commercial service.

Presently, there is no comparative pricing data on hydrogen-based fuels and fossil fuels. The travelling public expectation is that once the technology matures, hydrogen-based fuels will be less costly resulting in more cheaper air travel.

Comments

"Hydrogen-powered aircraft: The future of aviation"