Race to save sea urchins

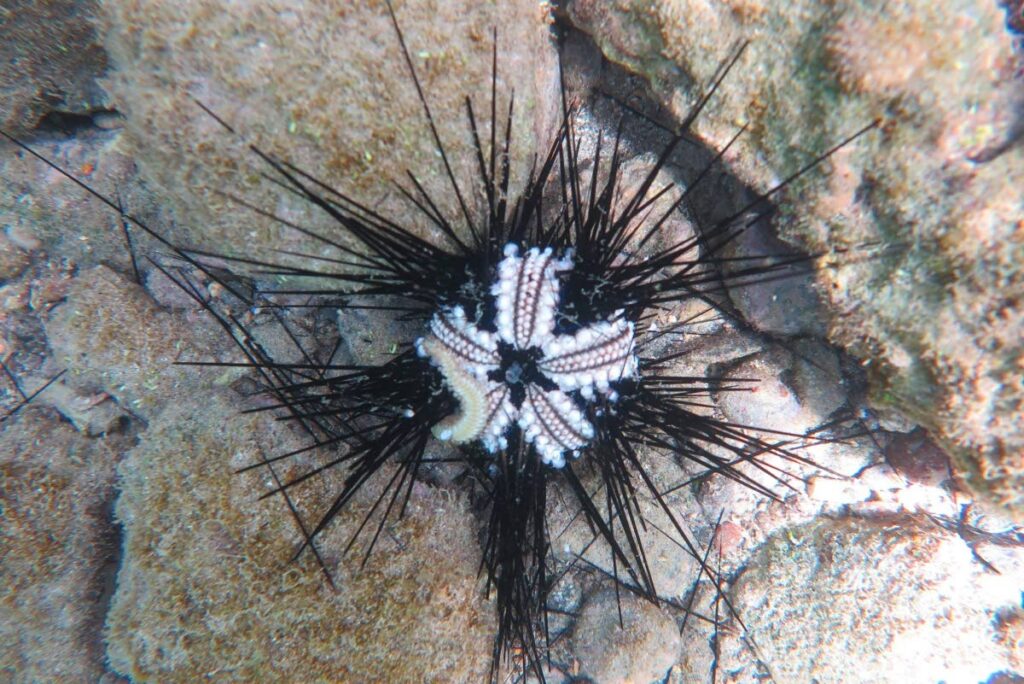

When last did you see black sea urchins on Tobago reefs? Anjani Ganase reports on the fate of sea urchins in the Red Sea following fatal disease in the Caribbean.

Scientists are in shock after discovering a mass die-off event of the black sea urchin (Diadema setosum) in the Gulf of Eilat in the Red Sea over the last couple of months. On reefs that were covered in these urchins, they now encounter dead skeletons and spines on the bottom. This black urchin, which is native to the Red Sea, invaded the Mediterranean Sea through the Suez Canal many years ago. The population which occurred in the thousands on the reefs in the Mediterranean were wiped out in July and August 2022.

The first reports of the sea urchin mortality came from Greece and Turkia and was originally thought to be a localised event. While that die off did not seem a threat to the species that is invasive in the Mediterranean Sea, the rapid spread of the disease across thousands of kilometres in the Eastern Mediterranean raised concerns among scientists for the native populations occurring on the other side of the Suez Canal on the reefs of the Red Sea. This year reports of sea urchin mortality came from within the Gulf from Jordan, Egypt and Saudi Arabia signifying spread to the Red Sea. Reports were made of sea urchin deaths at depths of 20 m and in aquarium tanks where it is likely that the pathogen was pumped from the sea.

Caribbean sea urchins

This die-off event comes a few months after mass mortality of the long-spined black sea urchin (Diadema antillarum) in the Caribbean which was reported in the US Virgin Islands, Jamaica, Mexico, Florida, and the Lesser Antilles. Investigations to find the pathogen revealed that a tiny single-celled ciliate that invaded sea urchin and spread throughout the tissue. Scientists have never encountered a ciliate that was pathogenic to sea urchins before. This infection resulted in the death of the urchin within two days. The Caribbean is no stranger to such events, having experienced a mass mortality event during the 1980s which was much more widespread and devastating. The disease wiped out 93 - 100 per cent of the species across the region within a couple years.

The long-spined sea urchins in Tobago were infected a few months after the die off was detected along the Panama coast. This mortality event, set Caribbean reefs on a path of extreme vulnerability to disturbance. Without the presence of the sea urchins, Caribbean reefs are at risk of being overgrown by algae in the aftermath of any disturbance event that results in coral loss as fast-growing fleshy algae quickly occupy empty spaces on the reef. Algae is usually kept in check by sea urchins and other herbivores that live on coral reefs. Sea urchins are very efficient at keeping clean surfaces to encourage coral recruitment. Today, the long-spined sea urchin continues to be scarce on Tobago’s reefs where they dominated 20 years ago. While the culprit of the 1980s event was never uncovered, scientists will now re-investigate historical records and samples to see if the ciliate was also responsible for the previous outbreak.

Eastern Atlantic sea urchins

Other urchin mortality events also occurred in 2009 along the Eastern Atlantic spreading from Madeira to the Canary Islands, over 400 km. The outbreak was spread by a bacterial infection aggravated by warmer sea-surface temperatures. The 2009 outbreak resulted in the death of 65 per cent of the species of sea urchin (Diadema africanum) and populations began recovering in the years following the disease outbreak. Unfortunately, a second outbreak in 2018 did more damage, tipping many reefs of the Canary Islands to a macroalgal dominated state after a 93 per cent loss of the sea urchin without recovery.

- Photo courtesy K Marks, sourced from AGRRA Diadema Response Network.

The scientists from Tel Aviv University who study the already fragile reefs of the Red Sea fear that these reefs will suffer a similar fate to that of the Caribbean reefs and the Canary Islands. Some even fear that this may be the point of no return for many of the Red Sea reefs considering the escalating climate change. Now researchers are scrambling to determine the cause and speculate the possibility of it being the same ciliate pathogen, given the similarities in the symptoms and rapid spread and rate of death of the urchins. They join the Caribbean researchers in the race for a treatment – a method to stop the spread or to increase survival after infection. At the same time, they work to safeguard a brood stock of sea urchins that can be used to raise stocks that can be returned to the wild in the future; hopefully to prevent species extinction. Management of the reefs includes efforts to limit the nutrient rich freshwater runoff to slow the growth of the microbes and staunch the spread.

The Caribbean needs to implement similar practices to safeguard sensitive species which are vulnerable to the onslaught of disturbances (hurricanes, bleaching and disease outbreaks) that our reefs are expected to face because of climate change. This is in addition to the long history of human exploitation and pollution. We must wonder whether Caribbean reefs are also past the point of return for large-scale resuscitation.

References

Clemente, S., et al. "Sea urchin Diadema africanum mass mortality in the subtropical eastern Atlantic: role of waterborne bacteria in a warming ocean." Marine Ecology Progress Series 506 (2014): 1-14.

Hewson, I et al., A scuticociliate causes mass mortality of Diadema antillarum in the Caribbean Sea.Sci. Adv.9,eadg3200(2023).DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adg3200

Lessios H. A. (2016). The Great Diadema antillarum Die-Off: 30 Years Later. Annual review of marine science, 8, 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-122414-033857

Rotem, Z., Schmidt L. M., Roth L., Corsini-Foka M., Kalaentzis K., Kondylatos G., Mavrouleas D., Bardanis E., and Bronstein O. 2023 Mass mortality of the invasive alien echinoid Diadema

setosum (Echinoidea: Diadematidae) in the Mediterranean Sea. R. Soc. open sci.10230251230251 https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.230251

Comments

"Race to save sea urchins"