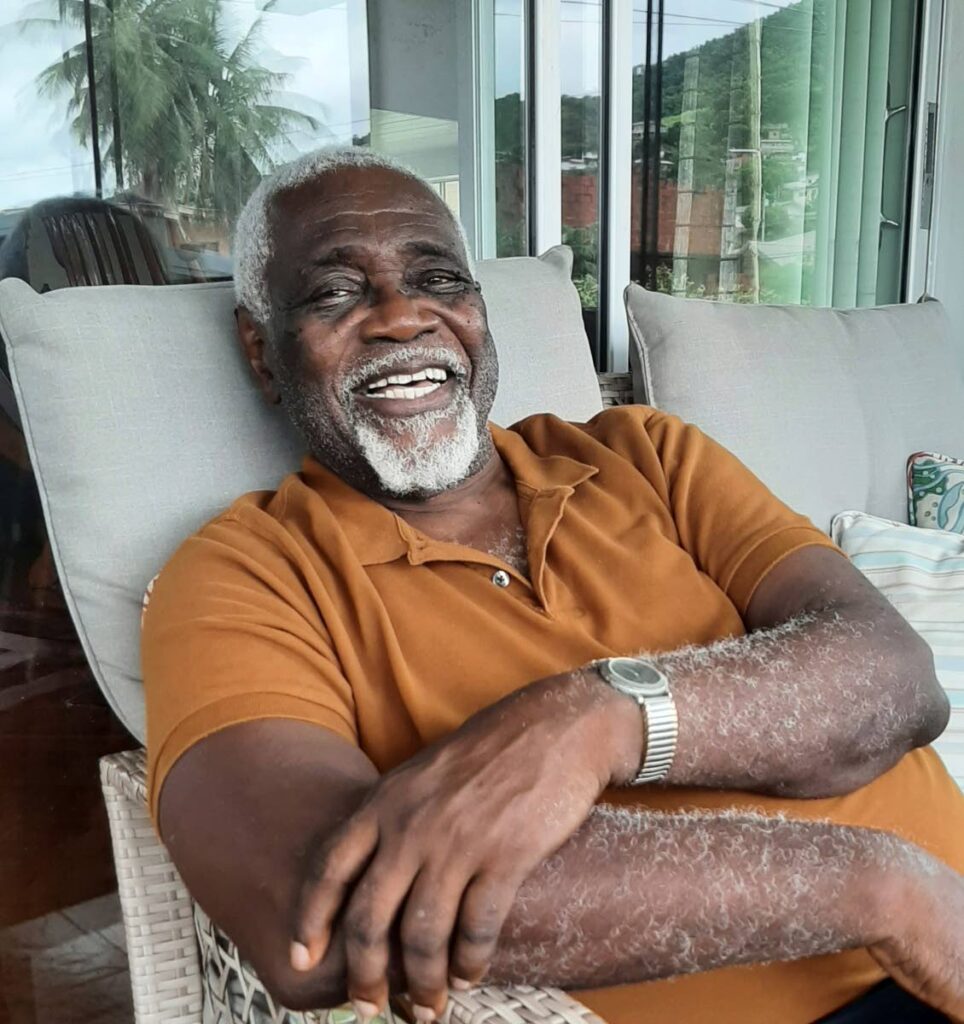

Gordon Rohlehr – What Then?

Accolades have poured in for Professor Emeritus Gordon Rohlehr, the Guyanese-born UWI, St Augustine academic, early poet, critic and thinker who died just as the season of calypso starts, when it was he who made that popular genre his own critical and theoretical territory. He was the man who argued that calypso was on a continuum with “high” art.

Rohlehr has left us a large body of work from his career-long endeavour to describe and understand what a local Caribbean aesthetic could be. He broke new ground analysing calypso and the work of Sparrow, addressing the relationship between the language used by our poets and novelists and the language used in our speech and song and how that has developed into our uniquely local creative aesthetic. I remember the heated 1970s debates about the rightness and wrongness of literature in the Queen’s English as we had been taught it when we actually spoke Creole. Rohlehr, with some of his contemporaries, made calypso and other emerging forms of cultural expression, such as dub poetry and rapso, into subjects worthy of academic study, which was essential as part of our decolonisation process. Seeing Louise Bennett speaking and performing in Jamaican patois on BBC TV in the UK back then was a revelation. The 1970s Black Power revolt in Trinidad proved that we are a multi-faceted and complex society and that we needed new tools to forge a veritable post-colonial society. Other countries in our region faced the same realisation. One could say that language and literature became another area of activism in the years after independence and Rohlehr was one of the leaders. His theorising was an important step in establishing a post-colonial literature, and he vigorously defended Kamau Brathwaite who had dedicated himself to it.

The UWI reports that he started the study of literature at the St Augustine campus in the 1980s and by all accounts Rohlehr was a phenomenally good teacher. Not only was his thinking and theorising stimulating, his teaching methods were anything but boring. He brought personal recordings to the lectures, and old journals and cuttings. Commenting on his career as a teacher, he said in an Anthurium interview, “My teaching has been a kind of conversation – a dialogue as opposed to a monologue in which students would have their own voices which I have been careful to affirm so that they would learn to take their voices seriously. We must not shun critical discourses which come from outside which could be very relevant and helpful in terms of understanding ourselves and our situation.” He came many times to the annual literary festival, the NGC Bocas Lit Fest, and he was known to start his tiny recording machine as the sessions started. We knew it was to advance whatever new book he was working on or possibly as a teaching tool.

Making literature accessible, as calypso is, to all was a strong motivating force. It is why he published many of his own dozen or so books and shied away from academic publishing, which could easily damage an academic career. His writing appeared in Lloyd Best’s Tapia and Trinidad and Tobago Review and other easily acquired and less expensive journals. He said he wanted his work “to come to the attention of the mass of the people who then could dialogue with it, dismiss it or hopefully become illuminated by some of its perceptions,” so he used broadcast media, too, to engage people in a conversation.

In 2014 the Bocas Lit Fest honoured Rohlehr by presenting him with the Bocas Henry Swanzy Award for distinguished service to Caribbean literature. The award acknowledges the role of those behind the scenes who have contributed to the growth of our literature as teachers, editors, mentors etc. Although he was responsible for a whole post-colonial area of academic enquiry and during a 40-year career mentored and mid-wifed a new generation of local thinkers, Rohlehr was very modest in his acceptance. Similarly, in his 2009 acceptance speech, entitled What Then?, of an honorary doctorate from the University of Sheffield in the UK, he spoke a little coyly about his hesitation over prizes and laurels, and having come to realise that it was not humility that informed his attitude, but rather apprehension.

He had borrowed from WB Yeats’s four stanza poem also called What Then? about a man who had spent his life as expected and achieved success, and at the end of each stanza the question appears, what then? In his 2020 memoir Musings, Mazes, Muses, Margins, Rohlehr considered his own life’s work in four bullet points. He reasoned that he had worked 1) to vindicate and add value to the efforts of his ancestors, 2) to vindicate the efforts of all those who educated him, 3) to repay the people of the Caribbean whose blood, sweat and considerable tears funded his UWI Open Scholarship, 4) because the redemptive power of work countervails life’s futility, anguish, doubt, bitterness and failure.

We are all the better for his anything but futile 40 years of toil. RIP Gordon Rohlehr.

Comments

"Gordon Rohlehr – What Then?"