What Rohlehr taught us

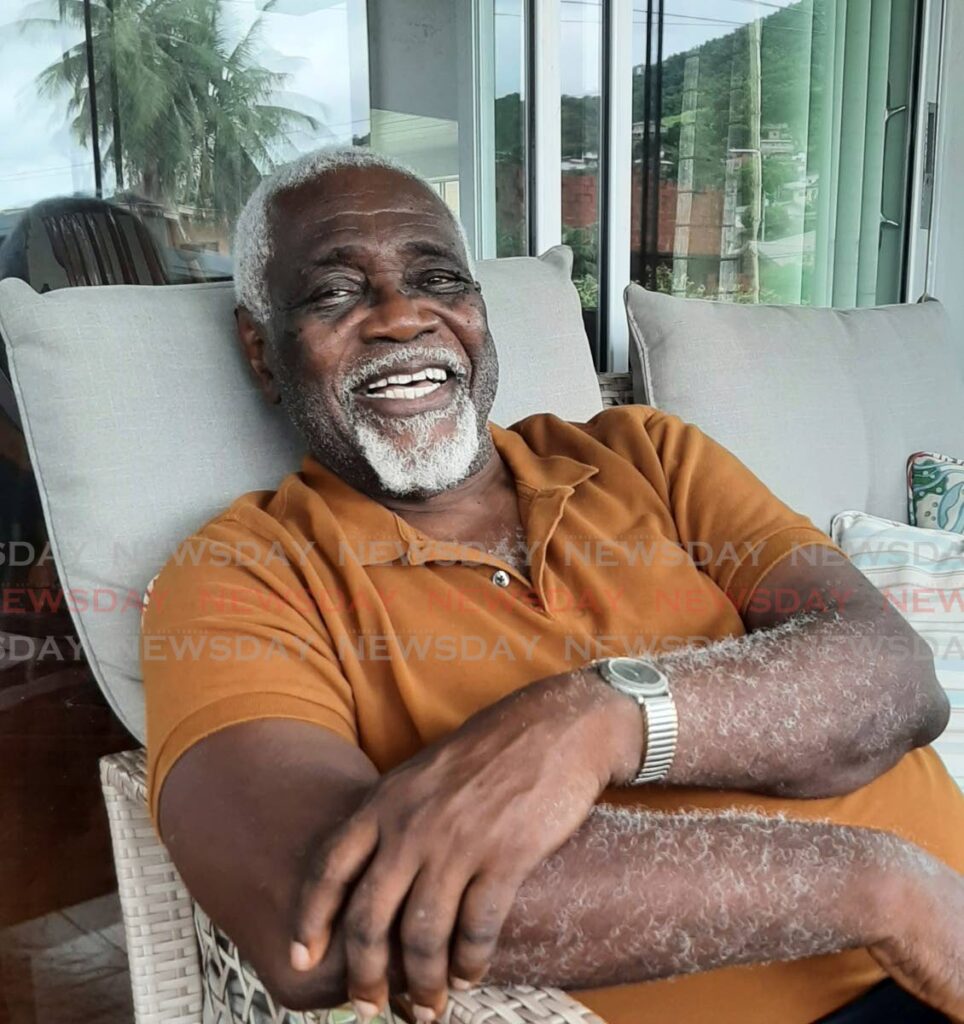

THROUGHOUT his long and distinguished career, Gordon Rohlehr, who died on Sunday at 80, occupied a rare space as a Caribbean academic.

He straddled two worlds: the world of the calypso and the world of the academy.

But if there was one single argument he embodied it was the idea that there is, in fact, no distinction between the two worlds.

The calypso, he showed us again and again, is, at its height, a magnificent intellectual construct, a barometer to measure the pulse of our society as we transition from a colonial state.

Of course the breadth of Prof Rohlehr’s work was as wide as the issues he canvassed were complex.

He wrote important tracts on figures such as Kamau Brathwaite, Derek Walcott, VS Naipaul, Earl Lovelace, Lloyd Best, Pat Bishop and Jeffrey Chock, among others. Subjects such as soca parang often jostled alongside things like moko jumbies and J’Ouvert.

This was because in his vision cultural studies went hand in hand with political analysis.

In a late essay, he called for the preservation of Caribbean cultural identity amid an increasingly loud onslaught of counter-forces.

“If we want to really preserve Caribbean cultural identity in the face of so many ambiguous pressures and tensions, we will need courage, confidence, self-knowledge and caution,” he wrote in 2006.

Prof Rohlehr’s many publications include: Calypso and Society in Pre-Independence Trinidad (1990), My Strangled City and Other Essays (1992), The Shape of That Hurt and Other Essays (1992), A Scuffling of Islands: Essays on Calypso (2004), Perfected Fables Now: A Bookman Signs Off on Seven Decades (2019) and the spectacular Musings, Mazes, Muses, Margins (2020).

But it is his insight into the calypso, particularly the work of Sparrow and the late Black Stalin, that has come to define his legacy.

Perhaps more than any other Caribbean academic, he has exposed generations to the nuances and intricacies of works which we have often taken for granted, missing their subversive qualities.

It is a legacy that stands alongside some of our greatest literary critics including Kenneth Ramchand and Merle Hodge.

We earnestly hope that scholarship of this calibre continues.

It is ironic that Prof Rohlehr has died at a time when there is a resurgent debate about the relevance of calypso within our Carnival traditions.

Some calypsonians have recently alleged censorship, while a casual review of calypso tent performances raises disturbing questions about whether modern calypsonians are up to the task of holding those who are in positions of true power to account.

At the very least, there has to be a preservation and dissemination, particularly at the tertiary level, of Prof Rohlehr’s criticism.

Perhaps some calypsonians, too, can learn a thing or two about their age-old art form by reading the professor today.

Comments

"What Rohlehr taught us"