State's covid regulations upheld by Privy Council

GOVERNMENT’S covid19 regulations, implemented in March 2020, have been upheld by the Privy Council.

In a unanimous ruling on two appeals that challenged the public health regulations, the London court on Monday also resolved a conflict on the balancing of constitutional rights with legislation that restrict some of them and the power of the Parliament to make such laws.

The decision was written by Lords Sales and Hamblen with whom Lords Reed, Hodge, and Lady Rose agreed. In March, the five judges heard arguments on the two appeals, reserving their decision at the time.

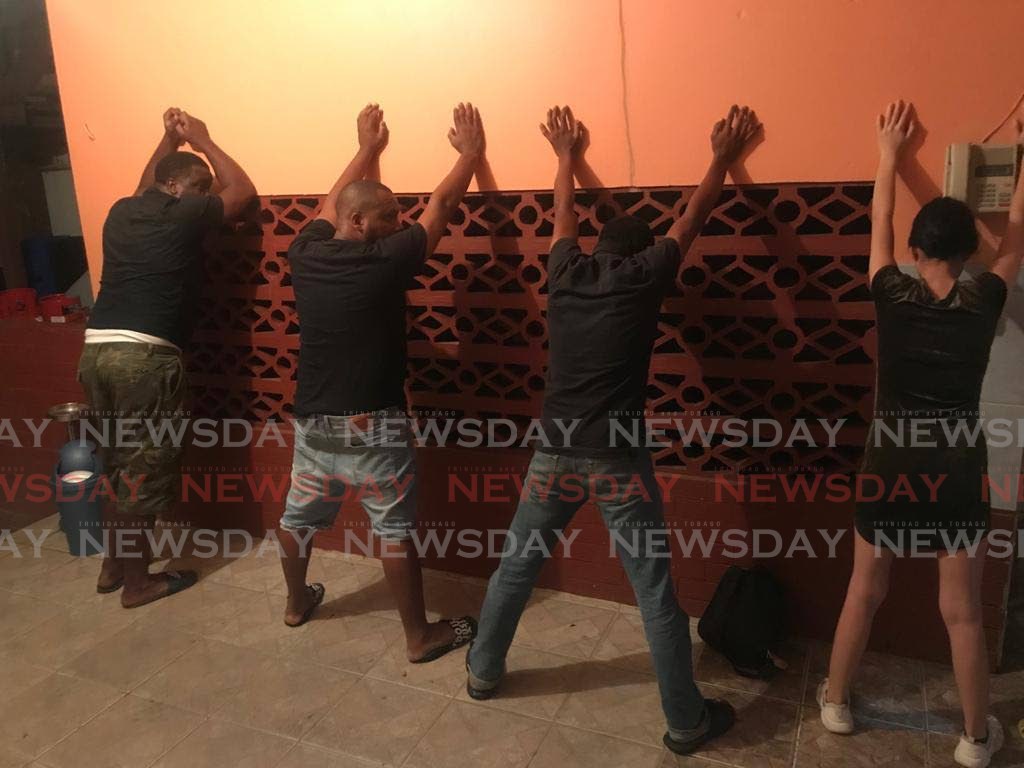

In one of the appeals, five men who were arrested at Alicia’s Guest House on April 9, 2020, and charged under regulations that limited gatherings to groups of no more than five people, challenged the regulations. In the other, Pundit Satyanand Maharaj challenged the regulations on the basis that the prohibition on gatherings did not apply to religious gatherings and was vague and uncertain, as it criminalised breaches of the guidelines for places of worship.

In September 2020, then High Court judge Justice Ronnie Boodoosingh dismissed the challenge of Dominic Suraj and the others, while partially upholding Maharaj’s challenge involving the regulations over criminal sanctions for breaches related to places of worship.

In April 2021, the Court of Appeal, comprising Chief Justice Ivor Archie and Justices of Appeal Mira Dean-Armorer and James Aboud, dismissed the appeal of the five men, ruling that the regulations passed under the colonial-age Public Health Ordinance (PHO) were not unconstitutional. The court also upheld a counter-appeal brought by the Office of the Attorney General to Maharaj’s challenge, reversing Boodoosingh’s decision on the issue.

In its ruling, the Court of Appeal held the decades-old public health ordinance was protected by the Constitution, and the regulations made under it were also protected from challenge by the savings clause, which insulates colonial legislation from review except by Parliament.

On this issue, the Privy Council judges said, “There is good reason to think that the framers of the Constitution intended that the regime in the Constitution should not displace the regime in the Ordinance.

“Both regimes set out useful powers which provide the government with options about how to proceed in the face of a public health emergency.”

They said a government that decided to respond to a “difficult public health issue cautiously and with restraint,” by employing powers under the ordinance, “should not then be exposed to legal challenges based on the contention that the President ought instead to have declared a public emergency.”

“The public interest requires that the government should be able to respond flexibly and with confidence that the measures it takes will not be unduly at risk of legal challenge. The framers of the Constitution cannot have intended that the authorities would be presented with a difficult dilemma about which powers they should use in the face of a public health crisis.”

The Law Lords recognised there was a division of opinion in the local courts on how the interpretation of fundamental rights, provided for in section 4 of the Constitution, and section 5, “saved” laws that existed before 1962, when Trinidad and Tobago gained independence from England.

“Having regard to the importance of this for the law of Trinidad and Tobago generally, the Board considers that it should revisit that issue,” they said.

In doing so, they held that the reading of rights, as subject to an implied proportionality qualification, was the “appropriate way to allow for the balancing of rights in conflict with each other which is required.”

“A very large part of ordinary legislation, passed by Parliament for good reasons of the public interest, must inevitably interfere with or operate as restrictions on those rights,” they said.

They also noted that in their view it was not plausible to expect that the framers of the 1962 Constitution and the preceding Republican Constitution in 1976 intended to “disable Parliament from taking ordinary legislative action in the public interest.”

“The natural solution to accommodate the inevitable friction which always exists between individual fundamental rights and democratic decision-making in a constitutional liberal democracy like Trinidad and Tobago is that conventionally adopted so often in such states, namely to require that interference with such rights should be permitted in the public interest, but only if the interference is proportionate to a legitimate aim.”

They also said to interpret section 4 rights as “absolute rights” would conflict with the nature of TT as a democratic state.

“The democratic nature of the state is declared and guaranteed by the Constitution.”

They noted if section 4 rights were read as absolute, then the rights of individuals will often be in conflict when legislative choices are made.

“...Reading the rights as subject to an implied proportionality qualification is the appropriate way to allow for the balancing of rights in conflict with each other which is required.”

They said Parliament was established as the body with authority to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the country and to read section 4 rights as absolute, then the “law-making power which Parliament enjoys under section 53 (of the Constitution) to take measures in the public interest would be severely and unjustifiably undermined.”

“...The rights have to be balanced against each other. In the Board’s view, the only way in which the rights can operate coherently at the level of ordinary executive action by public officials is if they are interpreted as limited rights, which naturally implies they are subject to a proportionality qualification.

“It cannot sensibly be suggested that the solution to this sort of situation is legislation passed by the super-majority procedure…Parliament does not have the time or resources to react to each and every individual case which might arise by seeking to pass an act by a super-majority; and it would not wish to pass legislation by a super-majority in advance which authorised intervention whenever a social worker wished, without any control by reference to the rights at stake, since that would permit them to take action even when it would be undesirable and contrary to the rights and interests of both children and parents.”

They held the solution contemplated by the framers of TT’s Constitution was that “Parliament should create general powers for public officials by ordinary legislation in the usual way” and officials exercising those powers would do so while respecting section 4 rights. This, the Privy Council said, would allow them to take effective action in the public interest.

In their ruling, the judges said despite the constant jurisprudence from the apex court on the correct approach to the interpretation and effect of section 4 rights, the matter had “remained a matter of controversy in the local courts.”

“In the Board’s view, the correct interpretation of the Constitution is that the rights in section 4 are to be read as incorporating an implied proportionality test.

“The proportionality approach for bringing into account both individual rights on the one hand and the general interest of the community on the other is aimed at ensuring that a balance is struck between the two.

“The stronger the public interest in issue, the greater the interference with individual rights which may be permitted without there being any violation. “Generally, in a democracy, it is the democratic institutions which have the primary responsibility to identify the public interest and what is required to promote it,” they said.

On the separation of powers argument, the Lord Lords said, “In a democratic state, the courts must be expected to be especially respectful of the choice made by Parliament to pass legislation in that form and slow to substitute their own view of the necessity for and proportionality of the measure taken.”

At the appeal, it was the State’s contention that the minister had the power under the ordinance to make the regulations and this right was saved so, too, the minister’s power to make regulations under the ordinance.

Dealing specifically with Maharaj’s appeal, they said a guideline was advisory in nature and its purpose was to provide information on how something should be done “not what must or must not be done.”

“ A guideline is not a tramline,” they said, explaining that it qualified its operation and set out the boundary of the criminal law on spacing requirements so it could not be considered as having created legal uncertainty.

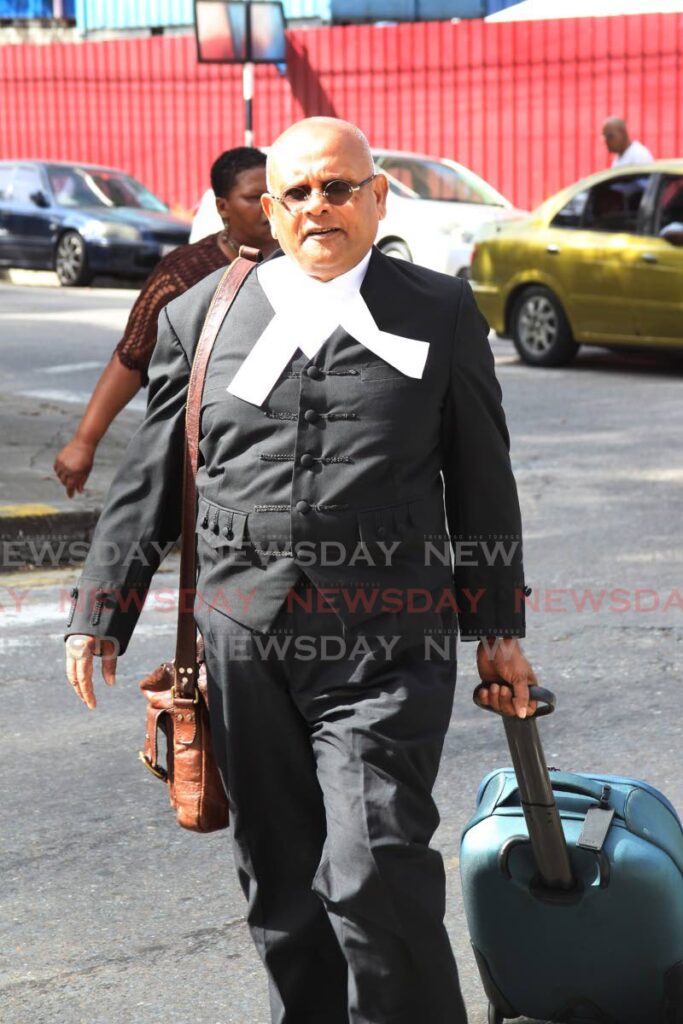

Representing Suraj and the others - Marlon Hinds, Christopher Wilson, Bruce Bowen, and Collin Ramjohn - were Peter Knox, QC, Anand Ramlogan, Vishaal Siewsaran, Adam Riley, and Ganesh Saroop.

Ramlogan led Kate O’Raghallaigh and Adam Riley for Pundit Maharaj while the State was represented by Thomas Roe, QC, Fyard Hosein, SC, and Natasha Jackson.

Comments

"State’s covid regulations upheld by Privy Council"