Climate impact on people, planet at heart of capital market change

“Mandate impact disclosure to achieve the sustainable development goals (SDGs) and accelerate behavioural change in capital markets” is the first recommendation from the Impact Taskforce (ITF), an independent, industry-led taskforce supported by the G7 Presidency, published on December 13.

The Rt Hon Nick Hurd chaired the ITF and brought together 120 leading voices from business, investment and public policy, representing over 100 institutions across 40 countries. The mandate of the ITF in answer to the critical question: how can we accelerate the volume and effectiveness of private capital seeking to have a positive social and environmental impact?

The chair of ITF Workstream A, which developed this first recommendation, was Douglas Peterson, president and CEO, S&P Global. The recommendations of the ITF are transformational, as they move the purpose of accounting towards impact value generation for people and planet.

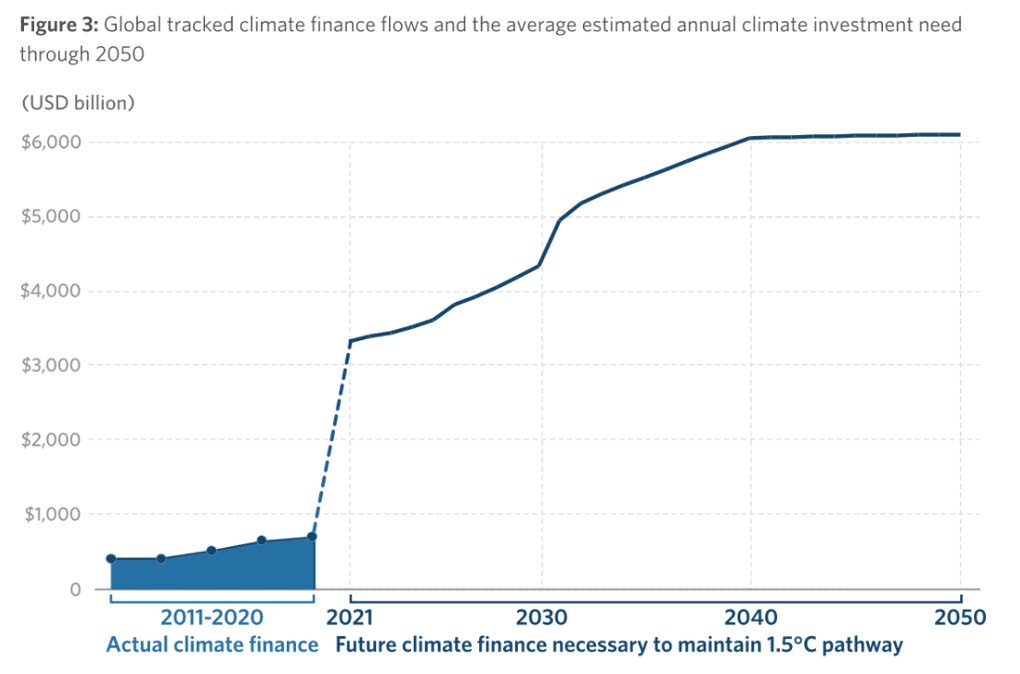

For the world to achieve SDGs, there will never be enough public money. According to a new report by the Climate Policy Initiative, investments must increase by at least 590 per cent to US$4.35 trillion annually by 2030 for us to be able to meet the climate objectives, maintaining a 1.5-degree C pathway (the Paris Agreement, SDG 13).

It is anticipated that the funding should come from such sources as corporations, households and individuals, commercial state-owned, and development finance institutions, and government budgets. Given the scale and the risks involved, co-ordination, policy, legislation, regulation, harmonisation, standardisation, and assurance are all needed in order to scale up fast.

Moving beyond modern portfolio theory

What are the (financial) reasons that investors are increasingly addressing issues such as climate change, gender diversity, mining safety, governance of technology, etc?

For Jon Lukomnik and James Hawley, a large part of the answer lies in the demise of the “perfect myth” that ruled capital markets for the past 70 years: modern portfolio theory (MPT). Economist Harry Markowitz introduced MPT in 1952, and later received a Nobel Prize for his contribution. It was a powerful framework for how to assemble diversified portfolios of assets in a way that they maximise returns for any given level of risk.

The underlying assumptions of MPT have been debated for a long time, because it has been shown they do not reflect important realities. Nevertheless, the theory was able to explain about six-25 per cent of variability in returns associated with the idiosyncratic risks associated with individual firms and the specific conditions they encountered. On that basis, MPT has produced impressive results. Whole industries developed around pre-packaged, diversified products, such as mutual funds (think, for example, of Unit Trust Corporation).

One of the effects was that market participants grew in size because they were joining together in diversified portfolios. This growth exacerbated one of the underlying weaknesses in the MPT assumptions.

MPT is focused on mitigating the risks of individual stock selection (alpha risks) – not the systems, the markets, in which the firms operate. In other words, MPT models do not deal with the systematic risks that affect whole markets (beta risks).

Prof Markowitz confirmed these limitations of MPT in conversation with Leslie Clarke, managing director of Murphy Clarke Financial Ltd, when he visited TT.

However, over time, two things became clearer: first, a large part of returns are determined by systematic market risks. These risks affect, according to Lukomnik and Hawley, up to 75-94 per cent of the returns to investment.

In other words, there are many environmental and social dimensions of markets that are financially material to companies, and therefore they also affect investor returns. William Frater, founder at Kutumikia in South Africa and my colleague on ISO/TC309 governance of organisations, points out: these risks are absolute, and while relative outperformance may be possible, the investor has still lost. as the whole market declines and is thus poorer. The bigger these systemic risks get, the bigger the impacts. And if all markets become exposed to the risks, then we cannot diversify out of the systemic risks.

The second thing that happened is that investors and companies have grown in size – by a lot! MPT thinking put all the focus on the non-systematic risk to companies, eg from their competition, or operations, but not on how the companies or the investors themselves might be affecting the market, or the real world. Large companies and large investors have an effect on the markets, the regions, the countries and the natural environment in which they operate. This means there is another material effect: the effect of the company and investors on society and the environment.

Together, these two directions of materiality are referred to as "double materiality."

What does it mean for the Caribbean?

In addition to an ever-increasing consensus that a number of planetary boundaries have been breached and the urgency of correcting course and scaling up to achieve the SDGs (no country is currently on target), this requires understanding the fundamental transformations we are witnessing in the capital markets and a number of market characteristics common in the Caribbean.

We are now in a position to come to the main insight: investors, companies, politicians, regulators, and large parts of society have realised it pays to protect and regenerate the system in which they are operating. It pays to achieve the SDGs not only because it is the morally right thing to do, but also because they improve and save the markets and systems on which we depend.

This is why investors, companies, regulators, standard-setters and others are coming together throughout the world as "beta-activists" to invest strategically to reduce their negative and increase positive effects on nature and society, and thereby on their markets.

Seen from this perspective, it is clear that the calls by the ITF reflect an ongoing and fundamental transformation of capital markets. Calls for the rapid operationalisation of the new IFRS-ISSB, the development of and adoption of the new ISSB standards, the proposed corporate sustainability-reporting directive in the EU, legislative and regulatory developments in the US, UK, Korea, Japan, China, Canada, etc – are all part of a movement in the same direction. The ITF reports notes that “emerging markets (and the Caribbean falls in that category) are often first-movers when it comes to early adoption of high standards as a differentiating factor.”

This is a vital opportunity for the Caribbean – in every way!

Dr Axel Kravatzky is managing partner of Syntegra-ESG Inc., vice-chair of ISO/TC309 Governance of organizations, and the co-convenor and editor of ISO 37000 Governance of organizations – Guidance.

Disclaimer: the views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of any of the organisations he is associated with.

Comments and feedback that further the regional dialogue are welcome at axel.kravatzky@syntegra-esg.com

Comments

"Climate impact on people, planet at heart of capital market change"