Mind the gap!

In 2015 the governments of all 192 UN member states agreed on 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which sets out a 15-year plan to achieve the goals.

In 2019 the UN secretary general, Antonio Guterres, reported at the SDG summit that the world has made progress towards its destination of opportunity for all and a healthy planet but that “we are far from where we need to be. We are off track.”

By one estimate, we will not achieve the goals as agreed in the next eight years, but may be some 52 years off track, even before covid19 hit: “At the 2019 rate of progress, it would be 2082 before all SDGs are realised – and that was before covid19, which is likely to set back progress by at least another ten years” (World Benchmarking Alliance, quoting 2020 Social Progress Index results).

In fact, the World Benchmarking Alliance finds in 2021 “not one country on track to meet all SDGs by 2030.”

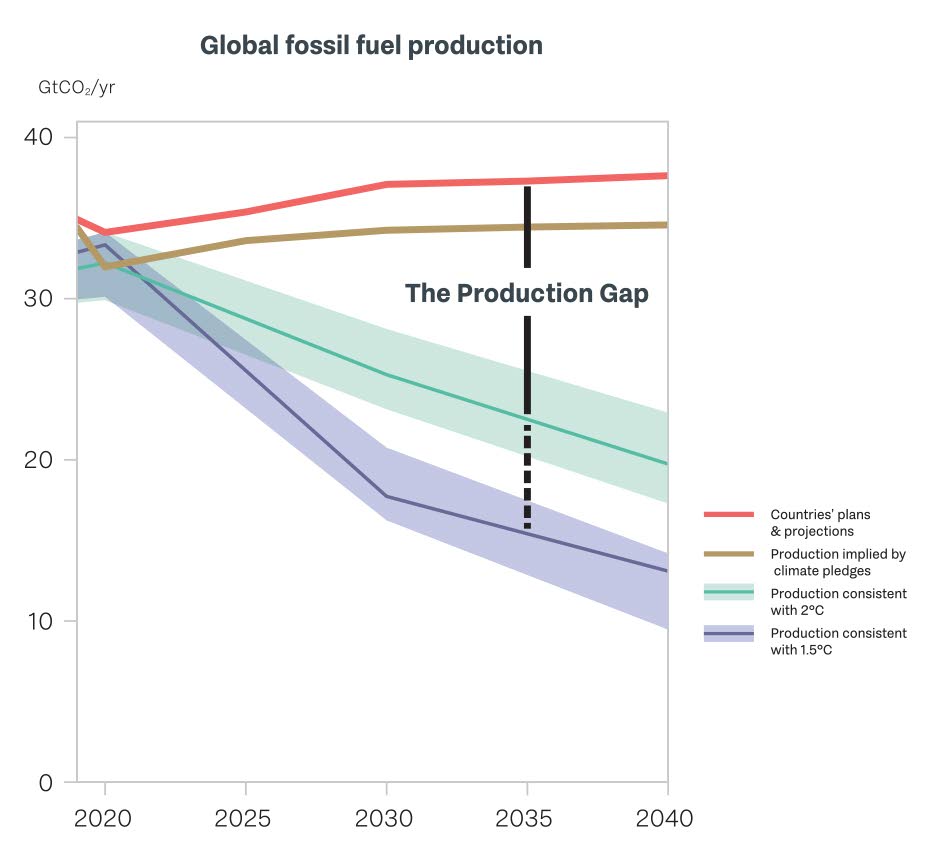

One report published in October 2021, the Production Gap report, which examines the gap between current plans by governments for the fossil fuel energy sector with those that would be consistent with the climate ambitions under the Paris Agreement 1.5 or 2°C increase, finds that recent national energy plans and projections lead, in aggregate, to 110 per cent more fossil fuels in 2030 for 1.5°C increase and 45 per cent more than what would be consistent for 2°C (and by 2040 the excessive growth is 190 per cent and 89 per cent respectively).

Standards and assurance are necessary

Three things are certain – the world’s problems are real and increasing, companies have awoken to the fact that there are great risks for laggards as well as great opportunities for agile and connected companies, and reliable information is key for decision-making.

At the level of their global headquarters, the “big four” auditing firms have not only recognised this, but are also banking on it by investing vast amounts to ready themselves to provide assurance beyond financial values – preparing to include assurance on non-financial value contributions to sustainable development.

Improved data, information, and audits will be absolute necessities. All development signs point in one direction: a path involving performance beyond financial and minimum levels towards maximum contributions to sustainability, regulation, and assurance. The days in which governments, investment funds and companies can get away with greenwashing based on declarations and glossy reports full of "giving back" activities, and pledging support for cherry-picked SDGs and vague assertions of good governance are going to come to a rapid end.

How to get beyond ‘blah, blah’

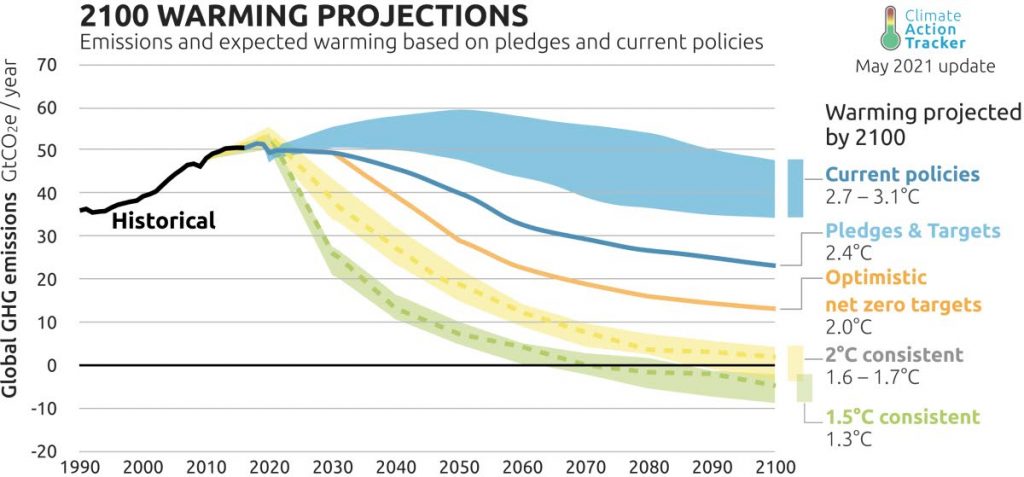

The world’s youth, including Greta Thunberg, are losing patience with continued "constructive dialogue." At the recent Youth4Climate conference, Ms Thunberg warned of "creative carbon accounting" and criticised world leaders for engaging in “blah, blah, blah” for the past 30 years, while adding 50 per cent of all CO2 emissions since 1990 and a third since 2005.

There needs to be real, meaningful, science-based, and assured action.

So what should companies that want to seriously contribute to sustainable development do? UNDP recently published SDG Impact standards for enterprises, bond issuers, and private equity funds. The enterprise standard applies to all enterprises – irrespective of size, geography or sector.

The unique contribution of the SDG Impact enterprise standard is that it helps organisations integrate impact management into their strategy, management approach, disclosure, governance, and decision-making practices. In addition, UNDP is developing a voluntary assurance framework and SDG Impact seal.

In a recent conversation with Jeremy Nicholls (assurance framework lead for the SDG Impact standards), he explained the shifts that the SDG Impact standards enable organisations to make in this way: “The SDG Impact standards are a decision-making framework designed to help organisations put in place the processes to assure that they are contributing positively to sustainability and the SDGs. The standards enable a shift from measuring ‘how much’ to ‘Are we making decisions at the rate we need in order to have a positive contribution against those targets we need to achieve?’

"That means assessing risk and considering the risk not just from the enterprise's or the entity's point of view but considering the risk tolerance of the people and planet experiencing the consequences of an organisation’s operations.”

These standards are process standards, not dissimilar to some ISO standards. They do not assess the actual contribution to sustainability, but they provide the basis for performance that is more likely to be contributing positively to sustainable development.

That means that organisations are considering the material impacts, or consequences of activities, informed by stakeholders who experienced those consequences and the requirements for sustainable development.

The SDGs themselves are a set of agreed goals and form part of the sustainability context within which organisations operate and they inform organisations in their understanding of their material impacts.

One of the most important aspects that companies and organisations in general, including governments, need to understand is that cherry-picking individual SDGs. then simply reporting that some quantitative or qualitative contributions were made to those SDGs. is not good enough even as a minimum level.

Instead, minimum levels should be informed by a science-based target or a globally agreed framework, and if those don’t exist, then there must be a clear explanation for why a certain target can be considered a reasonable minimum level.

Everyone needs to understand that the most prevalent current method of reporting. ie that they did a bit more than last year, or that they had no negative impact, does not constitute a positive contribution.

Nicholls further explained that:

If we're going to achieve the level of sustainability that we need by 2030, then we need to make sure that we have ambitious and rigorous goals against which we are managing our performance so that so that we're doing as much as we can.

We must maximise our contribution to sustainability and the SDGs (not merely meet minimum level).

We have to ramp up the level at which we are making decisions, choosing between options, and try to choose the option which is going to have the most positive impact; we have to do this all the time at all levels within an enterprise from operations all the way up to business models and purpose.

We have to consider whether the purpose or the way we are creating value or the strategy itself needs changing.

The way in which we change decision-making has to be reflected at all levels within an organisation.

Making decisions against these requirements is going to mean making decisions where you may not have "perfect" data and therefore we need to have an awareness of the associated risks, risk where the consequences are experienced by your stakeholders.

In this way, SDG Impact standards aim to drive more private investments and activity into where they are needed to support delivery of the SDGs by 2030. Governing bodies and management teams that apply the standard can close the gap between current practice and the practices needed to achieve the SDGs, while promoting continuous improvement, affect integrity, and accountability.

Dr Axel Kravatzky is managing partner of Syntegra-ESG LLC, vice-chair of ISO/TC309 Governance of organizations, and the co-convenor and editor of ISO 37000 Governance of organizations – Guidance.

Disclaimer: the views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of any of the organizations he is associated with.

Comments and feedback that further the regional dialogue are welcome at axel.kravatzky@syntegra-esg.com

Comments

"Mind the gap!"