Tobago conundrums

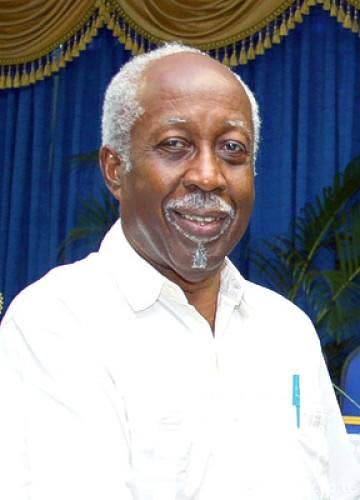

REGINALD DUMAS

ON NOVEMBER 28, 1996, our Senate debated a new Tobago House of Assembly (THA) Bill, shortly thereafter to become law, which among other things made provision for a body with 12 elected seats. In her contribution, Independent Senator Dr Eastlyn McKenzie asked a prescient question: “What will be the procedure if there is a tie?”

To which the Attorney-General, Ramesh Maharaj, replied: “(This) is a matter which the government considered. The policy of the bill is that we do not want to have strict divisions in Tobago…(but to have) more consensus and unity…If there is a tie, it would probably force people to work together. For that reason, it was deliberately left out.” The Opposition PNM raised no objection to this line of reasoning.

Maharaj also assured Dr McKenzie that a tie was “not likely to occur.” Well, we know better now, don’t we. The unlikely has in fact occurred; “strict divisions” have emerged; “consensus and unity” are bad words; and no one has been able to “force people to work together.” Parliament has now hastily adopted a bill for an Assembly with 15 elected seats, a figure whose political party connotations are all too transparent, and which was plucked, bewilderingly, from a joint select committee (JSC) proposal that has not yet even been debated, let alone approved, by the very Parliament. Faris Al-Rawi spoke recently about the next Carnival. Next? The ole mas’ has already begun.

The current occupants of THA political office insist they are acting within the law. As evidence, they cite section 34(4) of the 1996 THA Act, which says that the Executive Council “shall continue to discharge its functions during any period that the Assembly stands dissolved.” The Assembly was dissolved months ago and an election held in January. Members of the new Assembly were sworn in, but, because of the tie, and consequent political jockeying, the Assembly has not yet been properly constituted – no presiding officer has been elected, and the new Assembly therefore remains in limbo. In the meantime, so the argument goes, the dissolution of the previous Assembly holds sway, and the old Executive Council, somewhat altered in appearance, stays put.

But even if that interpretation is legal – and it is for the courts, not the THA, to pronounce – was this the intent of the law? Surely not, but why not ask Ramesh Maharaj? If his government, with Opposition concurrence, didn’t want a divided Tobago society but rather one in which people worked together in the best interest of Tobago, not of their political parties and themselves, what has happened?

Another point. Section 22(1) of the THA Act reads: “The Assembly shall continue for four years from the date of its first sitting after any primary election, and shall then stand dissolved, unless the Assembly, by resolution, dissolves itself at an earlier date.” The last Assembly dissolved itself at an earlier date; that’s fine. But note that the Assembly is to “continue for four years from the date of its first sitting…,” and that the Assembly elected last January has so far had no sitting at all. What might that mean in practice, if the present stalemate persists? That the current occupants of THA political office, whose party didn’t win the election, might still be there four or more years from now? Was that the intent of the legislation?

The preamble to our Constitution states that the people of TT “have asserted their belief in a democratic society in which all persons may…play some part in the institutions of national life and thus develop and maintain due respect for lawfully constituted authority.” Is “authority” in Tobago, such as it may be, lawfully constituted? Even if it is, would the present situation be thought consonant with democracy and ethics? Is “due respect” being engendered?

It isn’t only the short end of the THA stick that Tobagonians are made to grasp nowadays. The JSC on Tobago internal self-government recently visited Tobago. Like others, I assumed it would hear from all those who had previously submitted comments on the draft Tobago bills. But no: it met only with political parties; civil society, like the Tobago Lawyers’ Association, was excluded. Is this how “all persons” are to “play some part in the (country’s) institutions”? Do any of the Tobagonians on the JSC support this approach? If so, would they publicly indicate why?

And what of good governance, an indispensable element of a correctly functioning democracy? Transparency International defines it as “characterised as being participatory, accountable, transparent, efficient, responsive and inclusive, respecting the rule of law and minimising opportunities for corruption.”

Have Tobagonians been paying attention, especially at this time of emotion over internal self-government?

Comments

"Tobago conundrums"