A tree for life and literature

One of the few benefits of getting older is acquiring a broader range of experiences. Being an eternal optimist, I believe that new ones will come to me until the day I die, which will be the other most momentous day and experience of my life, after being born.

As an aside, I have often wondered why, in English and French, arriving on planet Earth is usually expressed in the passive voice, as if the infant fighting and pushing its way into the world had nothing to do with finally getting here, while bowing out is active – you die, but you were born. After all, we no more can ordinarily choose when we die than when we are conceived or emerge from our mother’s womb.

In Spanish, however, you do your own coming and going, but conception is expressed in the passive voice, as it should be.

I recently received news that a tree has been planted with my name on it in one of the most amazing places on the planet, the Magallanes Forest in the south of Chile, the most southern Latin American country before you arrive in Antarctica. It has aroused a profound sense of achievement in me, as if I had given birth to a rather special being. Indeed, a tree surviving in that part of the world in the harshest weather conditions is no mean feat. It is a test of the determination to live and thrive against the odds.

The tree is from the government and people of Chile as part of the inaugural Strait of Magellan Award for Innovation and Exploration with Global Impact. Five hundred years ago Ferdinand Magellan achieved the first circumnavigation of the globe and the Magellanic crossing through the treacherous strait between the Tierra del Fuego archipelago and the South American mainland.

According to the citation, “It marked a new way of seeing the world, uniting the Atlantic and the Pacific, representing the beginning of globalisation.”

I have never been to that most southern part of Chile, but my extremely well travelled son has, and he tells me it is one of the most beautiful places he has visited. My research validates his account of why a tree there is so special. Located by satellite, my native tree lies 45 degrees south by 72 degrees west (it is measured to the last inch) in the Imagen de Chile forest in the Magallanes region of Chilean Patagonia and is part of a well-conceived reforestation project. A link takes me to my tree, whose development I will be able to track. It’s the sort of innovation that the very award values and wants to promote.

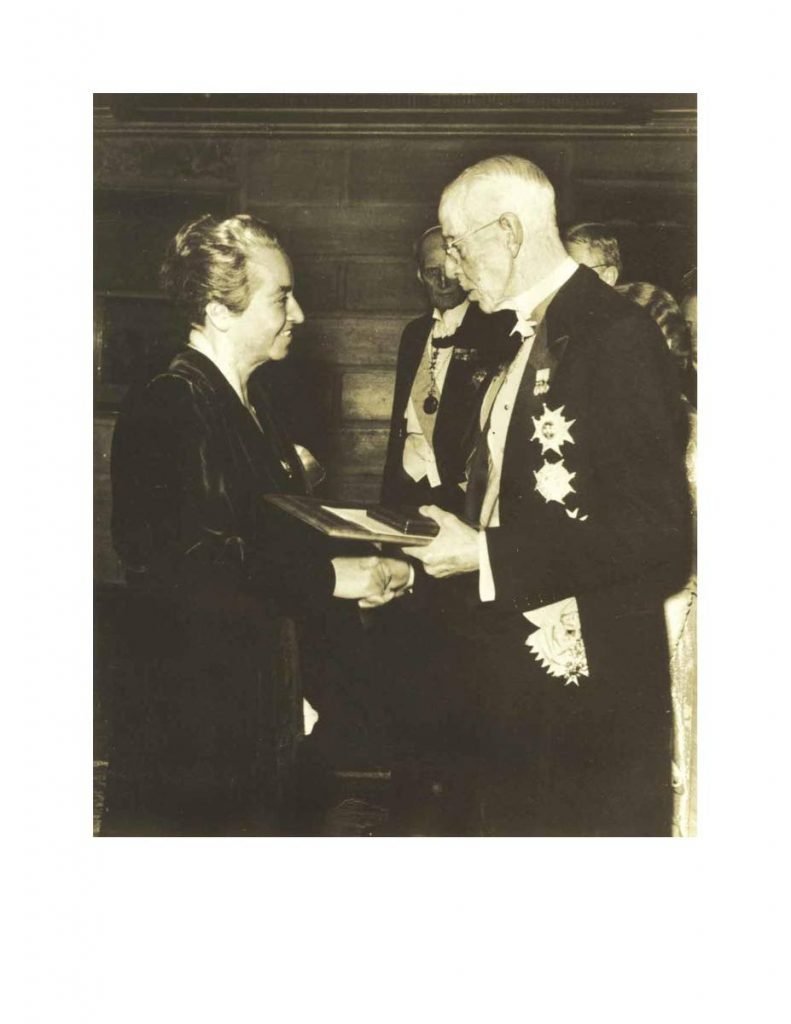

If Lucila Godoy Alcayaga, whose pen name was Gabriela Mistral (1889-1957), were alive today she would probably be a candidate for the Magellan Award, not least because she was Chilean and the country’s first Nobel laureate for literature, in 1945. She was also the first person of any gender from South America to take home the coveted prize.

She definitely embodied the spirit of the Portuguese navigator of 500 years ago who helped change the course of history. Her Nobel citation says, “...for her lyrical poetry which, inspired by powerful emotions, has made her name a symbol of the idealistic aspirations of the entire Latin American world."

December 10 is Nobel Day, when 2020 laureates will be generously rewarded for their significant work. It also marks the 75th anniversary of Mistral’s laureate. It is worth briefly remarking her illustrious career.

She was a child prodigy who defied her humble origins, taking at age 25 the name Mistral for the ferocious winds that whip through France, contorting trees into permanent distortions, very much as the winds of the Magallanes territory do to those trees. Maybe it was her intention to make an indelible mark by revolutionising the teaching of literature to children, but she wrote dozens of beautiful pieces of prose and touching poems which she used for her classes. There is a fine simplicity to much of her poetry, for that very reason. I think her creative writing was so central to her role as an educator that she hardly differentiated between writing for children and just writing.

The causes she spent her life supporting are also the themes of her work – the rights of women, children, the poor and the dispossessed. She was in the forefront of advocating peace in the period between WWI and WWII, believing we could create best in peaceful conditions. She lived abroad for most of her adult life, working as an educator and diplomat.

Mistral, were she alive, would be on the side of the translators in the current fight between longstanding Spanish translators of the poetry of the 2020 Nobel laureate for literature, the American poet Louise Gluck, and her London agents, who unceremoniously cut them off once she won the Nobel. Mistral understood the precise and important role of translators in allowing literature to cross borders and the debt owed to them.

When her government chose the eminent French poet and essayist Paul Valery to write the preface to her work and so improve her chances for a Nobel prize she rejected Valery, saying his Spanish was not good enough.

It is interesting therefore that she has hardly been translated into English. As a result, although some might rank her as a more sensitive poet than her fellow literary laureate from Chile, Pablo Neruda, his fame dwarfs hers and she is not at all well known internationally, in comparison to many Latin American writers, given her stature on the continent.

Key to Mistral’s winning of the Nobel prize in Sweden was the translation of a selection of her work into Swedish; only then was her enormous talent finally acknowledged, the first and the last Latin American woman to win such distinction, making her a legend.

Comments

"A tree for life and literature"