The church, slavery and indenture

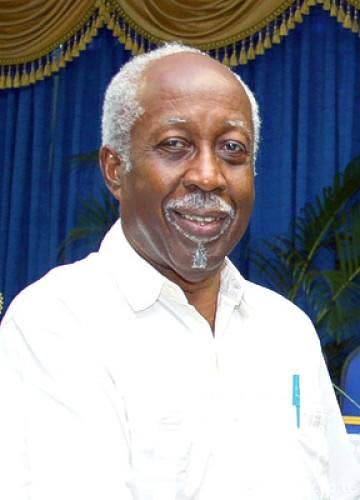

REGINALD DUMAS

I’VE ALWAYS encouraged people to write their own stories rather than have someone else write them. (Though I accept that autobiographies aren’t always free of embellishment.)

In the Caribbean, we have tended to swallow whole what is fed us by outsiders, and to regurgitate it whole as immutable truth – you just have to read several of the recent newspaper comments on the Columbus statue affair to understand that. What we should on the contrary do is bear in mind, and act on, the words of the late, great Nigerian writer, Chinua Achebe: “Until the lions get their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

I’ve been following my advice, and have already published two volumes of my recollections. Volume 3, which is on my experience of India, is essentially complete, and I’m now doing research for Volume 4. My current readings focus on the academic year I spent four decades ago as a visiting fellow at Oxford University. The book I was planning then – on microelectronics and its possible impact on the developing world – never did get written. But that is another story.

A recent article by Theodore Lewis on “The church and slavery” sent me back to some of my Oxford notes. Lewis points out one major fact we didn’t learn at school: the main churches (Anglican, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic) all owned slaves, and Protestant missionaries sought “not to end slavery, but to convert slaves to Christianity.”

My notes largely support his thesis. This is the late Elsa Goveia, UWI Professor of History, writing about the Leeward Islands at the end of the 18th century: “To secure toleration for their efforts to propagate the Christian religion among the slaves, the missionaries accepted the system of enslavement and the necessity for subordination which it created. It was held to be one of the chief tasks of all the Christian missions to inculcate among their Negro converts the duty of submitting to authority, particularly the duty of obeying their masters…[They preached] to the…slaves the virtues of industry, sobriety, honesty, faithfulness, and obedience.”

So Christian teaching happily coexisted with, indeed sub-served, the requirements of slavery. The Codrington family, high church Anglican, raised this mutually beneficial bedfellowship to the level of hypocrisy. Writing on “The West Indies in 1837,” Joseph Sturge and Thomas Henry stated that the island of Barbuda, which had been long-leased to the family by the British monarch, “was also a nursery for slaves…”

The Codringtons bred slaves in Barbuda for their estates elsewhere; the bigger and blacker, the better. Yet a member of the same family, without batting an eyelid, left a bequest for the establishment of what we know as Codrington College in Barbados, a theological institution. Breeding of slaves in one island, training in another island for propagation of the Gospel among slaves. What could be more pleasingly balanced in the sight of God and man?

But there were clergymen who tried conscientiously to carry out their duties and who, unsurprisingly, met with planter resistance. One such was Morgan Godwyn, a Church of England minister in 17th century Barbados. Godwyn, to whom a leading abolitionist, Thomas Clarkson, was to pay tribute a century later, argued that slaves had “naturally an equal right with other men to the exercise and privileges of religion.” To which the plantation owners replied, as expected, that “although [the Negro] bore the resemblance of a man, he had not the qualities of a man.” Is this view still held?

Indian indentured workers weren’t better regarded. In a letter written from Trinidad in February 1854, the Lord Bishop of Barbados complained that what the Indians really wanted to do was “save money and…avoid becoming Christians…(In Trinidad they were) content to be mere vagrants, and to live in a state of barbarism, without either decent clothes or wholesome food, or any of the comforts or advantages of civilised life.” How exactly vagrant barbarians saved money was not clear.

But he was hopeful; he saw possibilities: “Should…immigration continue…Trinidad will become a most important field for missionary labour, not only with regard to the immigrants themselves, but to the countries from which they come, to which some [of them]…may be induced and enabled to return as missionaries.” They say hope springs eternal. So also, it seems, does fantasy.

In February 2006 the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams, apologised publicly for the role played by his church in the abomination of African slavery in the Caribbean. I trust that our Caricom Reparations Committee has followed up on this and has had talks with Williams. And I await word from the other Christian churches.

In the meantime, don’t forget what Chinua Achebe said.

Comments

"The church, slavery and indenture"