Caroni Swamp, an untapped goldmine

Just as we are about to leave, the rains come.

“That’ll clear up in no time. You all still want to go?” Lester Nanan asks me and Newsday’s chief photographer Jeff Mayers. “Of course!” we respond, eager for the adventure into the Caroni Bird Sanctuary.

Nanan and some of his workers are preparing one of the open-top, flat-bottomed boats to take us on a trip up Channel 9, one of the Caroni River’s tributaries.

This will lead us to the lake where we will soon see the national bird, the scarlet ibis, coming in to roost for the evening among the mangrove islands that dot the Caroni Swamp.

Jeff and I are Nanan’s first guests in over 70 days. For more than ten weeks, since the mandatory lockdown to mitigate the spread of covid19 in mid-March, he’s had to shutter his business as, under the Public Health Ordinance, "A person shall not, without reasonable justification…be found at or in any beach, river, stream, pond, spring or similar body of water unless the presence of that person is essential for the carrying out or provision of a service specified in subregulation (2)”. Luckily, media falls into that category, so Jeff and I, and Nanan and his brother-in-law, Ali, our navigator, are fine.

Nanan understands why the lockdown was necessary but still, it couldn’t have happened at a worse time for him and his fellow tour operators.

“It was right at our peak time – Easter holidays and cruise ship season,” he told Business Day last Wednesday.

Nanan, 44, is a third-generation tour guide and one of the owners and operators of Nanan’s Eco Tours, a family business first founded by his grandfather Simon Oudit Nanan in the 1930s. His father Winston, a world-renowned self-taught ornithologist (bird expert), was instrumental in raising the profile of the swamp and lobbying the government for its protection (the Winston Nanan Caroni Bird Sanctuary is named in his honour).

“I’ve been following my father’s footsteps quite a while. It’s a family business together with my brothers. I do the bird watching part of it, taking people on bird watching tours across the entire country, from the northern range, the Aripo Savannah, the Nariva Swamp, Woodland. We were one of the first bird watching companies in Trinidad,” he said.

Nanan appears to be easy-going and laid-back, but make no mistake – he is very attuned to his environment. As we gently sluice through the muddy waters – the boats have been equipped with environmentally conscious engines that are low-noise and don’t emit hazardous exhaust fumes – his experienced eyes pick out animals that Jeff and I wouldn’t even have noticed had he not been with us, including a snoozing West Indian screech owl, a red-capped cardinal (the $50-bill bird), two coiled Cook’s tree boas and two caimans (that we missed).

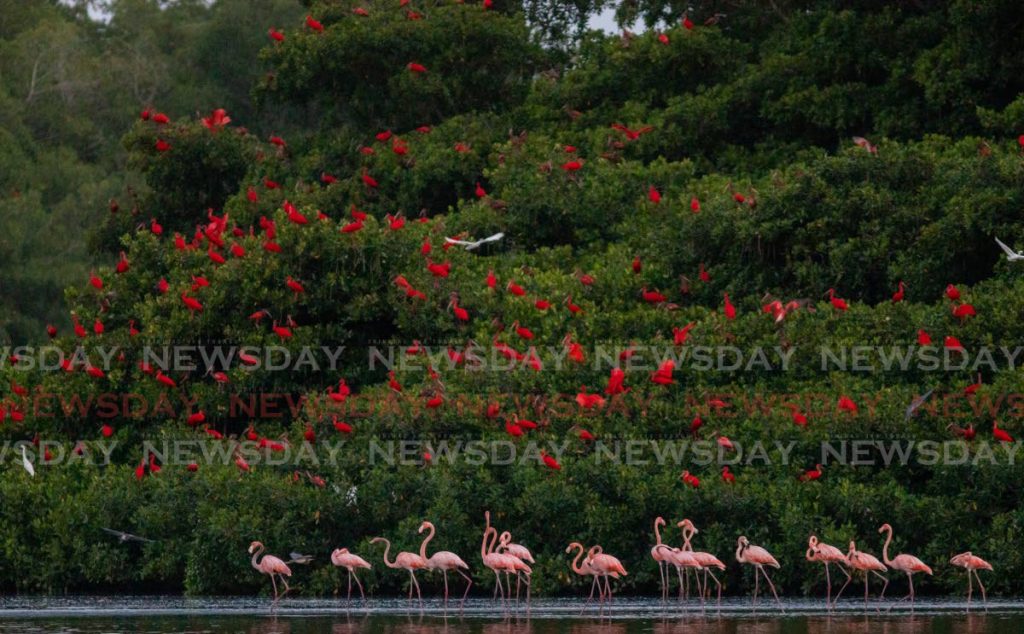

Nanan effortlessly rattles off facts and figures about our surroundings with the practised ease of a professional. The Caroni Swamp, for example, is 40 square miles of wetlands, and under the Ramsar Convention considered a wetland of international importance. It is home to over 180 species of birds, including the national bird, the scarlet ibis, and now a flock of bright pink American flamingoes who have made the swamp their home for the last five years. Both the ibis and flamingoes get their vibrant colour from the carotene in the crustaceans they feed on, which also enhances the deep midnight blue of the blue herons.

“Birdwatching very popular now all over the world. People come to Trinidad because of how easily accessible these places are. You can just drive off the highway and get to the Caroni Swamp. Just off the Manzanilla stretch is the Nariva Swamp (the largest wetland in Trinidad). You get a diversity of birds (relatively close by) whereas in the rest of the world you have to travel for hours to get this kind of variety. So that’s the advantage we have,” he said.

It’s a growing market, with tourists coming from as far as Europe, Japan and India. “From the time they retire, that’s what people do – they pick up a pair of binoculars, buy cameras and start birdwatching.”

Nanan leads specialised birdwatching tours, taking clients deep into the forests of the northern range to find the elusive piping guan or pawi, a bird endemic to Trinidad and listed as critically endangered. There’s also the Trinidad mot mot (the $5 bill bird), which is found mainly in Tobago and in the high altitudes of the mountains. “People are amazed by those. And of course, the scarlet ibis and the flamingoes.”

The flamingoes in particular are evidence of the good work conservationists – and tougher legislation against hunters – have been doing to protect the swamp. In 2018, the scarlet ibis, already protected as the national bird, was declared and environmentally sensitive species and the fine for poaching raised to $100,000 from just $1,000 previously. Nanan said since then, especially after people have been charged for possession of ibis carcasses, poaching seems to have decreased.

Poachers usually hunt the ibis and ducks in the swamp, he said. But despite the stiff penalties, Nanan said nobody really monitors poaching. “We do our best to look out for the birds but we can’t do anything if the poachers have guns,” he said.

The Forestry Division is supposed to monitor and patrol the swamp but Nanan says they haven’t really been doing much for the past five years. “I don’t know why. Perhaps they don’t have resources? We do our thing from 2 pm to 7 pm when we are here. After that we don’t know what’s happening.”

As part of his duty, he and his team regularly clear the swamp of litter and even trim branches and fallen trees that might obstruct the water way. In the two weeks since Nanan last checked the watercourse, litter, including plastic bottles and bags, had floated along and was now strewn along the banks or floating in the water.

“The human race is very destructive so any habitat will strive better without any interruptions,” he noted. “We keep our distance and our statistics and share information with other operators and guides. My friends (in the industry) think like me. You have to have a passion for nature to do this business. It’s not only about the money.”

But, money is still important. Tourism might account for just about four per cent of the country’s GDP but it employs one in ten people. And with the covid19 pandemic, it has been undoubtedly the hardest hit sector, with international travel banned and domestic movement severely restricted over the last two and a half months. Nanan estimates the business depends on something like 60 per cent domestic tourists and 40 per cent foreigners. The Caroni Bird Sanctuary tour is a marquee attraction for cruise ship passengers, for example.

Nanan is a board member of the Asa Wright Nature Centre and treasurer of the Incoming Tour Operators’ Association, so he’s well aware of the industry’s predicament beyond his own.

The industry depends on the cruise ship industry from October to April. Bird watchers come in at winter time. Then there’s Easter vacation, July/August (summer) and Christmas when it does a large mix of locals and foreigners.

Tobago hoteliers got a $50 million grant allocation for upgrades, he said, but Trinidad tourism operators, as far as he is aware, received nothing. “We have been struggling to pay our workers, even half pay. Nobody got anything but still we have to pay NIS/health surcharge. Our workers still have bills to pay, some of them are renting. A lot of our workers on the breadline,” he said.

And the industry is widespread, not just tour operators: hotels, taxis, souvenir shops and restaurants all fall into the tourism and hospitality sector and all have been negatively affected by covid19.

Getting back to a similar stage as before covid19 will take years, he estimated, including finding a vaccine and tourist confidence in travelling. The country and the industry will also have to adapt to more stringent health and safety protocols to accommodate tourists. Until the borders reopen though, he’s encouraging “staycations.”

“Trinidad is a place that a lot of Trinis haven’t discovered yet. People don’t even know we have flamingoes. We want them to come and see what the swamp has to offer.”

In anticipation of reopening, Nanan is already preparing his facilities for social distancing and sanitisation, installing a sink for handwashing at the loading bay, and installing physical distancing markers. Boats that can normally carry 35 passengers will now carry ten. He even has branded masks already printed. Tours will be targeted to families and friend groups who can come for a two-and-a-half-hour tour, with refreshments included for $1,500. He’s also considering adding tours per day to accommodate as many tourists as he is able.

“We want to encourage locals to support us and when you support us, you support the environment as well,” he said.

As we move deeper into the swamp, it feels a bit eerie (at least to me, Jeff was unbothered). There’s barely any sign of civilisation, even though the Uriah Butler Highway is just a few kilometres away. It’s quiet and still, and the waterway is fairly narrow with a thick mangrove canopy on either side. Even though the water is shallow and clear, there’s a faint smell of sulphur that Nanan attributes to the decaying leaves and the mangroves breathing in the low tide.

Suddenly, we turn a corner and everything changes. The river widens into a natural lake dotted with mangrove islands. It’s vast, open and bright in the cool evening sunshine (the rains did indeed clear). And then, in the midst of the green mangroves and dark, black water, there’s a burst of pink – our first sighting of flamingoes, including a greyish youngling, which Nanan takes as a positive sign that the birds are nesting the swamp, truly making it their home. And then, as the sun dips lower, the first flocks of scarlet ibis come home to roost. Some head to the deep interior of the swamp, which Nanan theorises is probably because it’s nesting season. The rest, mainly younger birds (you can tell by their feathers – it takes about three years for the birds to achieve their distinctive vermilion colours), settle on the outer branches of the mangroves. They are the masters of this swamp, Nanan says, and the other birds – the blue herons and white egrets – know these trees belong to the scarlet ibis. “Where else in the world can you see this?” Nanan says in awe, even though he’s seen it hundreds of times. “What a sight.”

Comments

"Caroni Swamp, an untapped goldmine"