The ghost returns

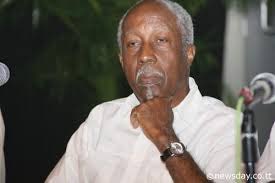

REGINALD DUMAS

Part I

FINANCE MINISTER Colm Imbert said recently that the Government would approach the Parliament next month for clarification of the role of the Office of Procurement Regulation (OPR) in government-to-government contracts.

He said: “It is going to be very difficult to enter into…a contractual arrangement with a sovereign government…to supply goods and services to Trinidad and Tobago and then subject that government to the Public Procurement Act because the other government may simply not be willing to do that.”

Before I comment on Imbert’s remarks, let me say immediately that I’m not at all a fan of such contracts. I accept that in certain circumstances they could be considered necessary, but having lived through the trauma and loss they caused us in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I would urge that we avoid them to the fullest extent possible. If we do use them, we should exercise the greatest care and caution.

Here are several deficiencies, drawn from my personal experience as high commissioner to Canada, that I listed in a June 2013 article titled “Government-to-government disarrangements.” Canada had been contracted to participate in two large projects: airport redevelopment at Piarco and Crown Point, and a maximum security prison at Golden Grove.

“One. Although the word ‘Canada’ was specifically defined as ‘The Government of Canada’ in the 1978 Memoranda of Understanding between our government and the Canadian, I quickly realised on getting to Ottawa in September 1980 that strong attempts were being made by certain Canadian officials to reinterpret it as ‘anything Canadian.’ I wrote Port of Spain to deplore this attempt ‘to relieve the Government of Canada of the essentials of its responsibilities under the agreements and to upgrade dramatically the involvement of the Canadian private sector.’

“Two. Within three weeks of my assumption of duty in 1980…I received a telephone call from the vice-president of one of the Canadian companies concerned inviting me to lunch. Over dessert he made his pitch: since my government trusted me, it would very likely accept my word on the estimated cost of the particular project, wouldn’t it? You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to figure that one out. I declined his proposal and reported the matter to Port of Spain…A year or so later, another company made a similar approach…My response was the same.

“Three. Another company requested a 25 per cent upfront fee after signing a contract which made no provision therefor. It also requested the assignment of the contract to a bank in Canada.

“Four. Yet another company, employed for something else, pressed for a contract to design and build the proposed maximum security prison. The company had never designed or built any kind of prison in its entire existence.

“Five. Many unsuitable Canadians were recruited for the projects. I remember one case in which my imprimatur was vigorously sought. I saw the man and was unfavourably impressed; I so warned Port of Spain, which nonetheless accepted him. Subsequently, his defects became too glaring even for the employer who had attempted to foist him on me, and he was fired.

“Six. Suggestions were being made by Canadian private sector operatives to the government in PoS that Canadian firms could provide management services for a fee and recommend different firms for different parts of a project, taking no responsibility for the performance or non-performance of those firms. These preposterous suggestions actually resonated with some of our colonial-minded bureaucrats. Or perhaps it was something more than colonialism at work.

“Seven. Extravagant per diem rates for work in (TT) were put forward. In one such proposal, for instance, a messenger would receive higher emoluments than I as high commissioner, and a clerk/stenographer more than our Chief Justice.

“And that was by no means all. Even some Canadians were appalled by the cynicism and rapacity of the deficiencies, apparent and real. One private sector person wrote me to say that the procedure employed by the Canadian government for the prison project ‘was not only expensive and misdirected but involved bidding on an obsolete package. The selection body in the bidding procedure had neither a proven knowledge of correctional planning nor proven experience in working abroad…(T)he system and planning process…is not only cumbersome but unworkable.’

“For his part, a senior Canadian government official…dismissed one company’s offering as ‘padded (and) excessive,’ and cautioned that ‘we must be careful to ensure that the contractor doesn’t constantly expand the scope of his activity at the expense of and to the detriment of the primary project.’”

My experiences were not unique; the whole government-to-government programme was a bitter and expensive lesson for us. Have we learned it? We will see.

Comments

"The ghost returns"