Remembering Kamal

WHEN Kamaluddin Mohammed died four years ago, his relationship with the political party he had helped create – the People’s National Movement (PNM) – had long been broken.

But a gesture by the Prime Minister helped heal that fracture of 28 years.

It was a visit that Dr Rowley paid to an ailing Mohammed, two weeks before the latter’s passing, that ended the distance that had developed when Mohammed was sidelined after the PNM’s massive defeat in the 1986 general election.

“It was a genuine and touching moment,” Mohammed’s niece Nafeesa Mohammed told Sunday Newsday in an interview on the fourth anniversary of Mohammed’s death.“It was the first time any top official from the PNM had visited him in all those years. They spent about 20 minutes together.

“The years of heartbreak he had after the change of the guards in 1986 – the ice was broken when Dr Rowley visited him.”

But there is still lingering pain in Mohammedville, El Socorro, where three generations of the Mohammed clan have lived since the 1930s, according to Nafeesa, herself a former parliamentarian.

That pain, she said, revolved around a February 2018 police raid on Muslim homes in El Socorro, including Mohammedville, over what the authorities called “a credible threat to disrupt Carnival activities.”

No one was charged, and Nafeesa lamented, “After a year, no one has launched an investigation into what happened.”

She said if Mohammed were alive he would have been heartbroken:

“After that kind of intrusion, they found nothing. That raid last year would have saddened him deeply, after the years he spent building a community and a nation.”

Nafessa herself was dismissed as legal adviser to the Prime Minister, three months after she got the post, after a Facebook statement alleging “a grave injustice and the cabal seems to be at it again.”

She told Sunday Newsday her uncle “would be troubled by what is passing as governance these days.”

The voice of Indo-culture

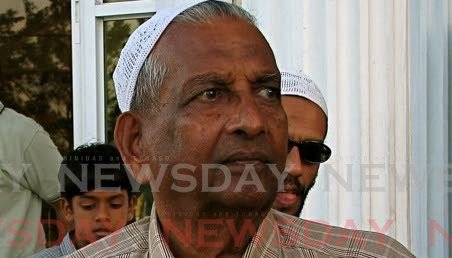

“Kamal” or “Charch,” as he was fondly called by those close to him, made history in 1947, when he became TT's first ethnic Indian broadcaster. He was 20.

Born on April 19, 1927, he was fifth in a family of 13 raised by Fazal Mohammed and Khajiman Kartoum, the children of Indian indentured labourers. He attended the Canadian Mission School in San Juan, then won a scholarship to Osmond High School.

He got his break on radio by chance. It resulted from the opening ceremony of Radio Trinidad, when he assisted a Muslim representative by translating the offered Arabic and Urdu blessings into English.

Mohammed, who was himself an imam at the mosque at Queen Street in Port of Spain, had been chosen as translator because he was versed in Islamic teachings and fluent in Arabic, Hindi, Farsi, and Urdu.

His performance so impressed the radio station managers that they invited him to produce and present a show for the Indo-Trinidadian community. Mohammed accepted the challenge and created a radio talent show, Indian Talent on Parade. He used the show to help create an understanding and appreciation of the art, culture, and religions of the local Indian community. The neophyte broadcaster went so far as to hire taxis to take orchestras to the studio to perform live. His one-hour Sunday show gave birth to Indian programming on local radio.

Mohammed's popularity in the Indian community eased his entry into politics.

In 1953, at 26, he won a seat on the St George County Council, and rose to become its chairman. It came, Mohammed once claimed, after he made a suggestion to Dr Eric Williams, then a fledgling politician, at an event in San Fernando, to form a political party.

“I had said that since we have so many (political) parties divided in Trinidad, and we are not yet powerful, just as we got together to produce a Caribbean callaloo of culture, we could do so with a political party,” he said in a documentary produced by the Parliament Channel.

Mohammed said Williams was at first reluctant, but warmed to the idea and asked him to formulate a plan.

He said Williams arranged to meet at his Indian restaurant in Port of Spain, and the talks widened at other subsequent meetings held at Williams’s home.

It’s an account disputed by political historian Ferdie Ferreira, a founding member of the PNM, who told Sunday Newsday he has seen no record of any meetings about forming a party.

“What I do know is that Williams was in demand to lecture, to feel out the politics. He did about 124; no inkling of forming a party.

“His real ambition was to become chairman of the Caribbean Commission, but his contract was terminated on June 21, 1955. The first serious indication Williams intended to enter politics came on that very day.

“Williams went to Woodford Square to speak on ‘My Relations with the Caribbean Commission’ and how he was treated. When he said, 'I was born here, I was educated at your expense, I am prepared to lay down (my) bucket here,' that was the first real signal.

"He didn’t say any party. But we knew that moment was when he announced his intention to start a political career. So the PNM was originated on June 21, 1955.”

Chambers chosen as PM

Whatever the origin of the movement, Mohammed and others helped Williams found the PNM, which went on to win the 1956 general election and held power for an unbroken 30 years.

The move changed the trajectory of young Mohammed's life. In 1956, he entered Parliament.

One-time St Joseph MP, Mohammed became the youngest government minister in the British Commonwealth when he was appointed minister of agriculture, lands and fisheries. He went on to serve in a number of portfolios, including public utilities, West Indian affairs, external affairs, local government and health.

In 1978, he was appointed World Health Organisation president.

Mohammed's most noted achievements included his work in securing regional economic co-operation. He assisted in pioneering the movement from the Caribbean Free Trade Area Agreement (Carifta) to the Caribbean Community and Common Market (Caricom), and the Caribbean Single Market Economy (CSME).

After Williams's death in 1981, president Sir Ellis Clarke bypassed Mohammed and another contender, Errol Mahabir, to appoint George Chambers his successor.

Mohammed had been considered one of Williams's right-hand men, so the choice of Chambers was interpreted in some quarters as a reflection of the PNM's sidelining of East Indians. Mohammed, Chambers, and Mahabir had been the three deputy political leaders of the PNM. Although Mohammed was the most senior and experienced of the three, Sir Ellis asked them to decide which one should succeed Williams.

Chambers reportedly declared that he had no aspiration to the position. The story is that neither Mohammed nor Mahabir was willing to yield, so Sir Ellis ended up appointing the reluctant Chambers.

Mohammed, however, denied there was any stand-off with Mahabir.

Clarke on the other hand, said, “...The result was that there was a deadlock. I had to resort to the one who had eliminated himself to hold the fort.”

In a 1995 interview with the TT Guardian, Mohammed was quoted as saying he had been passed over because of what he described as "political race."

Nevertheless, despite controversy over his alleged treatment, Mohammed’s loyalty to the PNM never appeared to wane, and he continued serving the party.

He was left out, however, when Patrick Manning brought in new blood after the party was thrashed at the 1986 polls by the National Alliance for Reconstruction (NAR), and was later rejected as a candidate for chairmanship of the party.

PNM disappoints Kamal

After he retired, and following 30 years as a symbol of a multi-racial PNM, Mohammed stayed out of active politics until he was summoned to national service by prime minister Basdeo Panday, who appointed him Caricom ambassador during the UNC's tenure in 1991-1995.

In supporting Panday in the 2000 general election, which Nafeesa contested for the PNM, the patriarch of one of San Juan’s largest Muslim families boasted that he still controlled the Muslim votes in the country.

In 2009, Mohammed was nominated by the National Council for Indian Culture (NCIC) for a national award. When the National Awards Committee did not grant it, NCIC president Deokinanan Sharma questioned the method of selection of recipients, which he felt did not appear to be transparent. Sharma said he was “very disappointed that a man who has done so much for this country has been rejected.”

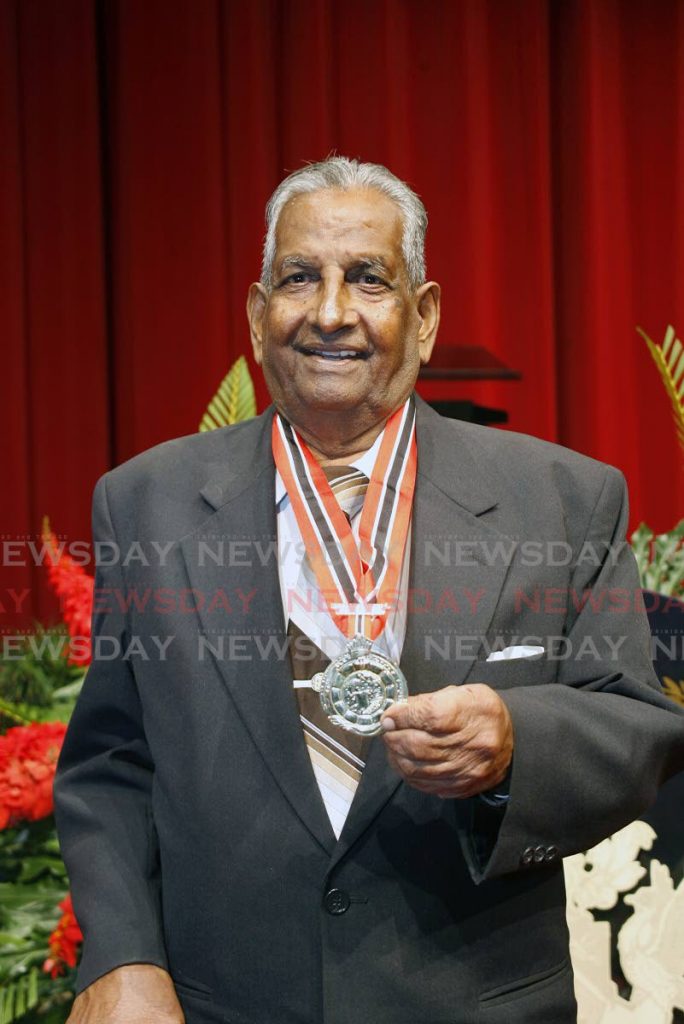

In 2010, Mohammed was honoured during the People’s Partnership administration, led by Kamla Persad-Bissessar, receiving the highest national award, the Order of TT.

In 2011, he received an honorary doctorate of laws from the University of the West Indies. In 2012, he was conferred with the Order of the Caribbean Community.

When Mohammed died on December 1, 2015, after ailing for two years, he was 88. He was the last surviving founding member of the PNM.

At his funeral, Nafessa said he was a giant of a man who remained humble. Also paying respects was Panday, who recalled some of the disappointments Mohammed faced in his decades of political service to country and region. The Prime Minister and Opposition Leader heaped praises on Mohammed for his contributions to the country.

Rowley said, “Mohammed's contribution to the development of TT is evident and our nation is grateful for his laudable contribution. His commitment to our nation has been outstanding and exemplary and we hope that it will continue to serve as an inspiration to others in this regard.”

On this month’s anniversary of his passing, relatives read verses from the Quran with an imam. Nafeesa said, “Immediate family members made supplications for his soul to rest in peace, for him to be forgiven for any errors in his lifetime and be elevated to the highest of stations in heaven – janaat-ul-firdous.”

Comments

"Remembering Kamal"