Jury or judge alone?

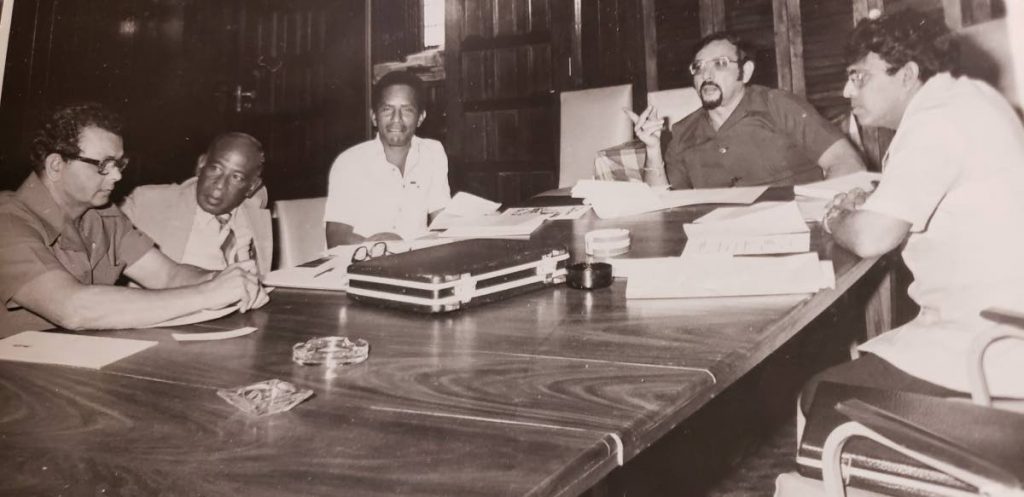

Jury. This is commonly described as “a body of (usually) twelve persons sworn to render a verdict on the basis of evidence submitted to them in a court of justice.” (Concise Oxford) In some jurisdictions, a jury may comprise nine or even six members. Last week’s panel discussion at the Hall of Justice on the choice between “a judge alone or a jury trial” re-introduced the subject from the 2017 Miscellaneous Provisions (Trial by Judge Alone Act), an act which caused quite a stir within and outside the legal profession.

Senior practitioner Pamela Elder SC threatened to cast her gown away if the jury were abolished. Israel Khan SC, among others, also protested. Last year, Chief Justice Ivor Archie claimed that trial by jury absorbed an inordinate amount of the court’s time, and if trial by jury continues, don’t blame him for delays. Juries do have their challenges ranging from members falling ill, prejudices, absenteeism, bribery, non-disclosure.

Recently, Justice Gillian Lucky dismissed a juror who indicated he “knew a witness in a murder trial which had already started.” (Express, Jan 12) It was not made clear what “knew” really meant. Citizens get quickly aroused when any move to abolish juries arises. Some judges are not entirely free from prejudice nor are they free from error in law or interpreting fact. The need to examine judicial candidates before appointment still stands. What is their position, for example, on abortion, same-sex marriages, jury trials, death penalty, homosexuality?

During my jury research in 1985, convict Andy Thomas sent me two ideas for jury reform: (1) Let jurors have secret votes (2) Give accused a choice between a jury or a judge alone. The question has been repeatedly asked: With all their community prejudices and low level knowledge of the trial process, are jurors really capable of arriving at fair verdicts based on the evidence? The twists and turns to this answer include the “right” of the judge to refuse or instruct the jury otherwise – as former judge Hubert Volney once did.

To help understand the role of jury prejudice in small, multi-ethnic societies, I constructed “a theory of evidential ambiguity” which proposed:

(1) The extent to which the evidence of both prosecution and defense appears “equally strong” or “equally weak,” to that extent would jurors become uncertain, and likely fall back on their homegrown stereotypes, prejudices, etc, even resisting unanimity in arriving at a verdict. The evidential situation to them (at least some) would be ambiguous.

(2) If however, the evidence from the prosecution appears relatively weak while that from the defense appears relatively strong, then jurors are less likely to exercise prejudice, stereotyping, etc. in arriving at their verdict. The situation is rather clear.

(3) Similarly, if the evidence from the prosecution appears relatively strong while the evidence from the defense appears relatively weak, then jurors are less likely to exercise prejudice, stereotyping in arriving at their verdict. (R Deosaran, Trial by Jury: Social and Psychological Dynamics, UWI, 1985)

Professor Derek Chadee’s thesis (2002) gave further confirmation of these predictions. These predictions will occur in ethnically-mixed or gender-mixed juries. Of course, there is more, for example, lawyers skilled in jury trials possess several techniques in raising doubts even over seemingly “strong evidence.” The jury aside, however, the structure and process of criminal trials contain their own slow-downs.

The new legislation (not yet proclaimed) allows the accused to choose between facing a jury or a judge alone. The accused also has the option to change his or her mind after a reasonable time. The legislation also requires judges to provide written reasons for their ruling. On this occasion, CJ Archie wisely noted that this legislation would not have any big impact on reducing the heavy trial backlog.

He noted the 700 people waiting between five to ten years for trial in murder cases. Director of Public Prosecutions Roger Gaspard, sharing that view, noted the serious deficiencies facing trials, such as better case management and witness protection. What about the all-too-regular adjournments due to non-appearance of police witnesses and lawyers, missing case files? What about abolishing preliminary inquiries? A 2013 inquiry into Remand Yard inmates heard a high proportion complaining how their paid legal representatives fail to contact or represent them properly. Apart from juries, what about these problems?

Comments

"Jury or judge alone?"