Bring Ayyub and Mahmud home

Every society has a duty of care to its next generation. As parents, grandparents, guardians and families our children mean more than anything. Our primary instinct is to protect them.

It is with dismay then, that I came to realise in the weeks before Christmas, that the Trinidadian government has knowingly left two vulnerable young children in Roj camp in Syria for months, maybe a year.

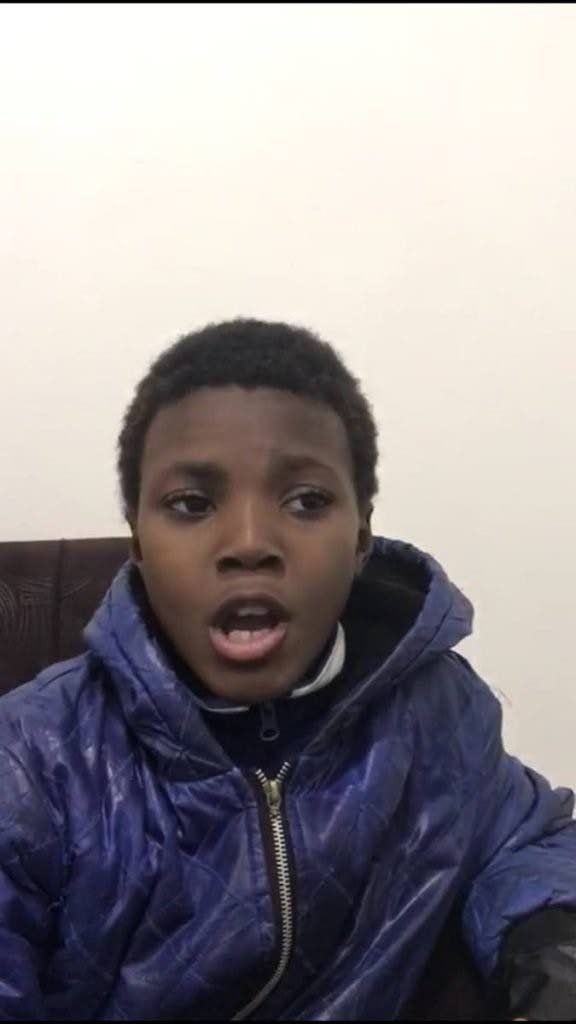

Ayyub Ferreira was born on Father’s Day 2011. On his third birthday, in 2014, his mother took him to the beach with his brother Mahmud and sister Baiyyeenah.

That laughter-filled day was the last time Felicia Perkins-Ferreira saw her sons. In the evening, their father Abebe Oboi Ferreira picked them up while their mother was resting and took them to Syria to join ISIS.

The couple’s relationship had been through its ups and downs. Felicia says she was “given” to Abebe by her mother as a gift, to marry, when she turned 16. She had known him since she was eight, growing up as friends attending the same mosque in Port of Spain.

After they married and had Mahmud, they divorced, then reconciled and had Ayyub, but soon separated again. Felicia has recently found a new partner, but the damage her first husband has done is immense.

While she dozed that evening after the beach, Oboi said he was taking the boys to his mother’s.

“I was sleeping so I said ok,” Felicia told me, sitting in an alcove at West Mall. All around us the sights and sounds of Christmas were a stark reminder of the bleakness her two sons are living in, miles away from home, school, their mother’s food and her loving arms. “I feel like I’ve been robbed,” she said, bursting into tears.

What the boys have been through nobody knows. They have been too scarred by their experiences to talk about what happened to them in Raqqa. In Camp Roj, where they have been since October 2017, they were briefly looked after by an American woman whose ISIS husband had been killed, like their father. She took them into her tent in January 2018 but was soon extradited. She told human rights lawyer Clive Stafford Smith they were traumatised when they arrived at the camp and would veer through anger, sadness and depression.

Since then, the camp’s humanitarian aid workers are keeping an eye on them. The boys are desperate to come back. They want their mum. Imagine being taken from Trinidad aged seven. How achingly you would long for the normality of home.

The question of how international governments, including Trinidad, deal with adults who went abroad to join ISIS is a complex legal matter. Trinidad’s Anti-Terrorism Act says it will indict anybody who “knowingly and without lawful excuse” joins or supports a terrorist organisation, whether inside or outside Trinidad – or travels to a geographic area where such an organisation operates. Some of the wives of dead ISIS militants have already been tried under local Syrian or Iraqi law and could be tried when they return home.

But Ayyub and Mahmud had no control over their actions or decisions, they committed no offences, they are the victims of an offence and should be treated accordingly. When they were taken, they were “doli incapax,” a Latin term that lawyer Dr Emir Crowne says applies under Trinidadian law. The common law doctrine holds that a child under the age of seven is incapable of forming criminal intent and cannot be tried for any offence. Between the ages of seven and 14, which Ayyub and Mahmud are now, there is a presumption of doli incapax, which according to Crowne can only be rebutted if the State shows the child held a genuine understanding that they knew what they were doing was wrong.

If the Trinidad government is dragging its heels on legal grounds, it should pick its heels up fast and acknowledge that children abandoned in Syria did not go there by choice. They would rather be going to the pictures at MovieTowne – just like any child, including our politicians’ own – than sitting cold and hungry in a detention camp.

When I asked Minister of National Security Stuart Young in mid-December how many Trinidadian citizens are in Syria, how many are at risk (eg vulnerable women and children) and what steps the Government is taking to bring them back, he ignored my messages.

This week he gave no reassurance or words of compassion for the children or their mother, telling Newsday there are “many agendas at play” and that Government will “abide by its process which is governed by national security and public interest.”

Now the eyes of the world are on Trinidad, wondering when the Government will bring these children home, dodging the issue is no longer an option.

Comments

"Bring Ayyub and Mahmud home"