Grandad’s past is a foreign country

Two years ago, my great-aunt Marie gave me the family tree her sister Gladys had spent years researching.

“You’ll have more use for it than I will,” she said ruefully.

I unravelled the scroll across her living room in Bradford. Next to her father’s name, William Runnels Moss, it said born Kingstown, St Vincent. Had my great-grandfather’s parents gone on holiday? Had my English family colonised that island on a whim? Looking closer, this was no whim. Three generations before him were all born there.

Unfinished family conversations about my great-grandfather’s mixed origins – which he’d kept secret – had faded over the years, with no conclusion. I decided to reopen them. I had to see the truth with my own eyes. I flew to St Vincent to find his records and solve the puzzle of a history written long ago.

It was evening when I landed, and the warm Vincentian welcomes were as pleasant as the cool breeze. The archives could wait until Monday. I wanted to explore the place my great-grandfather disowned.

From the top of Fort Charlotte, the flat and infinite milky sea stretched away from Tolkien-esque fairy-tale terrain. To the south was the magnificent silhouette of Bequia. Heading there on the morning ferry, boobies with pale eyes stalked the ship’s wake for fish as the craggy, bronzed cliffs of St Vincent retreated.

Back on the mainland, the Layou petroglyph drawings carved into volcanic rock by the indigenous Caribs a thousand years ago, and the gravestones of people long buried in a Georgetown church among coconut trees, mist-wreathed mountains, wandering goats and the turquoise ocean reminded me of my mission.

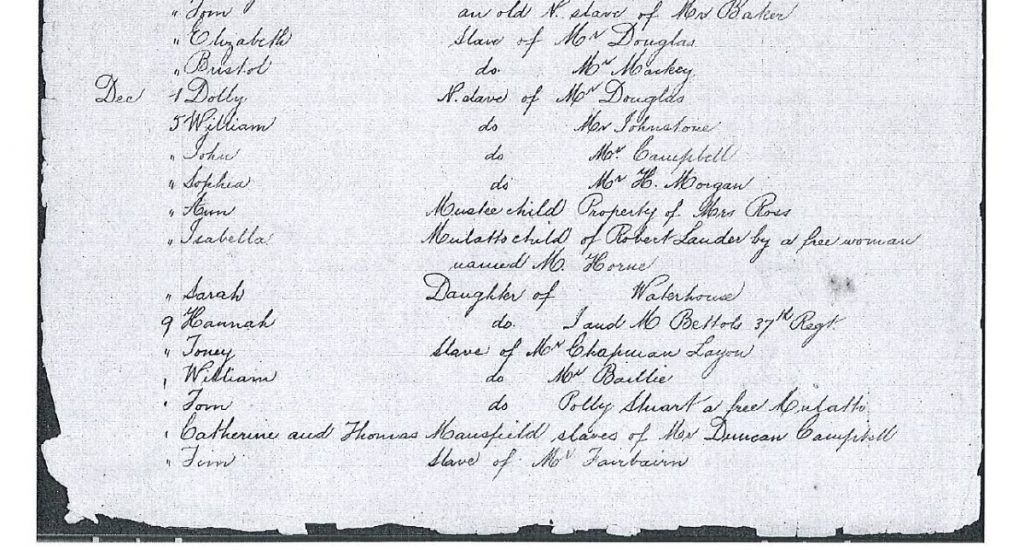

At the National Archives, I searched the digitally-scanned birth records from the 1750s to 1860s. The documents themselves were too brittle to be handled. The handwritten ledgers noted when a baby was “Mulatto,” “Coloured,” “Negro,” “Slave,” “Free,” “Property of…” or “Mustee.”

I googled that last word. It means one-eighth black ancestry – or “octoroon.”

In such an overtly racialised, colour-determined society, it’s not hard to comprehend why Grandad hid his origins once he moved to the almost exclusively white north of England.

I found the entry for his father, William Francis Moss, born in Kingstown, 1855, and the previous generation, born in the 1820s. But the first William Moss, born in 1802 and his wife Ann Marricheau, in 1798, I couldn’t find. Their unknown stories hold the missing link to why my European ancestors first came to the Caribbean.

Grandad was born in 1886 so his record would still be at the Registry, off a bustling street. The search room was busy with people looking through huge archaic-looking books of land deeds.

The supervisor brought out the leather-bound Index of Births 1882-1887 from a steel vault. Suddenly I felt nervous. What if he wasn’t in it?

I went through it once, twice… Had Aunty Gladys got it wrong? On the third time, near the bottom of a page I realised my great-grandfather’s forenames had been abbreviated to fit the column. In spidery ink, the words "Wm. Thomas R." (William Thomas Runnels). And beside them, his father’s name "Moss Wm. Fr." (Moss, William Francis)

He was there. He was unquestionably Vincentian. There was no sobbing like when I first visited Jamaica. This was a revelation.

So why did my great-grandfather disown this wonderful place that he, his parents and grandparents came from? Perhaps he never felt West Indian, but British instead? In those days, that was the indoctrinated norm – not just for white, passing or mixed people like him. Even black Caribbean people felt British. It was the motherland. It was their nationality. The country they died for.

Today, people take pride in coming from the Caribbean. Back then, it could hold you back. Race-mixing wasn’t accepted in England. Grandad was protecting himself and his family.

“I always knew there was something he was hiding,” his daughter-in-law told me when I interviewed the Yorkshire elders. “He was frightened of outsiders. Nobody ever came to the house who was an outsider.”

“You didn’t ask your father questions,” they all concluded.

There is another family “secret” harder to verify. According to letters I’ve seen, in 1911, before leaving St Vincent to fight in WWI, William Runnels Moss fathered a son, Frederick, with a black woman who he loved but was forbidden to marry by his family.

In 1930s Britain, he would have been so afraid of the repercussions of such a secret coming out that he dared not tell his children they might have a half-brother in St Vincent.

Frederick’s granddaughters, the Moss siblings Marsha, Karen and Mercedes, corresponded with Gladys from Kingstown and helped her with the family research. If the story is true, William Runnels Moss is their great-grandfather too and they are my cousins.

A hundred years after Grandad left for a now unrecognisable Britain, I arrived in an unrecognisable Caribbean. His Atlantic crossing was still driven by the forces of colonialism, but mine carried all the hallmarks of emancipation.

Comments

"Grandad’s past is a foreign country"