Triangulaires and OJT legislation

COLIN ROBINSON

caisott2@gmail.com

Who remembers the triangulaire? From four years ago.

Constitution reform commissioner Merle Hodge had joined a cross-section of outraged protestors outside Parliament. It seemed another promising sign of a people’s movement to rescue governance from the failures of Westminster. Some camped out until 4.30 in the morning.

Many had criticised the reform commission’s composition and months of national meetings as partisan and wasteful. But for me, those sessions were a unique experience of democracy, participants forced to sit and listen for three minutes to members of groups different from those we identified with sharing aspirations, fears and needs about a nation we share. Months after, people I shared little else with would greet me, reminding me how we knew each other. We had become legible to each other, given each other character and worth.

Government was clear the Opposition would not support its lofty reform proposals requiring parliamentary supermajorities. With the general election looming, as the commission wound down, Government put forward a hasty legislative proposal, barely discussed by the commission, and never in its public forums: Runoff elections in the marginal constituencies—where national elections are won. If in any of the 41 parliamentary elections, no candidate won a clear majority, voters would return to the polls to choose between the top two vote-getters.

The previous year, the month before local government elections, Government had, similarly, switched the method for selecting local government aldermen to a proportional voting formula. Now this. It was a bridge too far.

As the bill passed the House in the wee hours, all eyes turned to the nine senators on Parliament’s Independent bench, one of the few checks the current Constitution imposes on government power. Despite government’s automatic majority in the House, passing legislation requires support from at least one non-government senator.

There were vigorous civics debates over the public pressure on the Independents to withhold their votes. Intimidation, bullying, Government moaned. Some senators welcomed citizen advocacy as democracy at work. Others argued their role, like judges, was to stay above the fray.

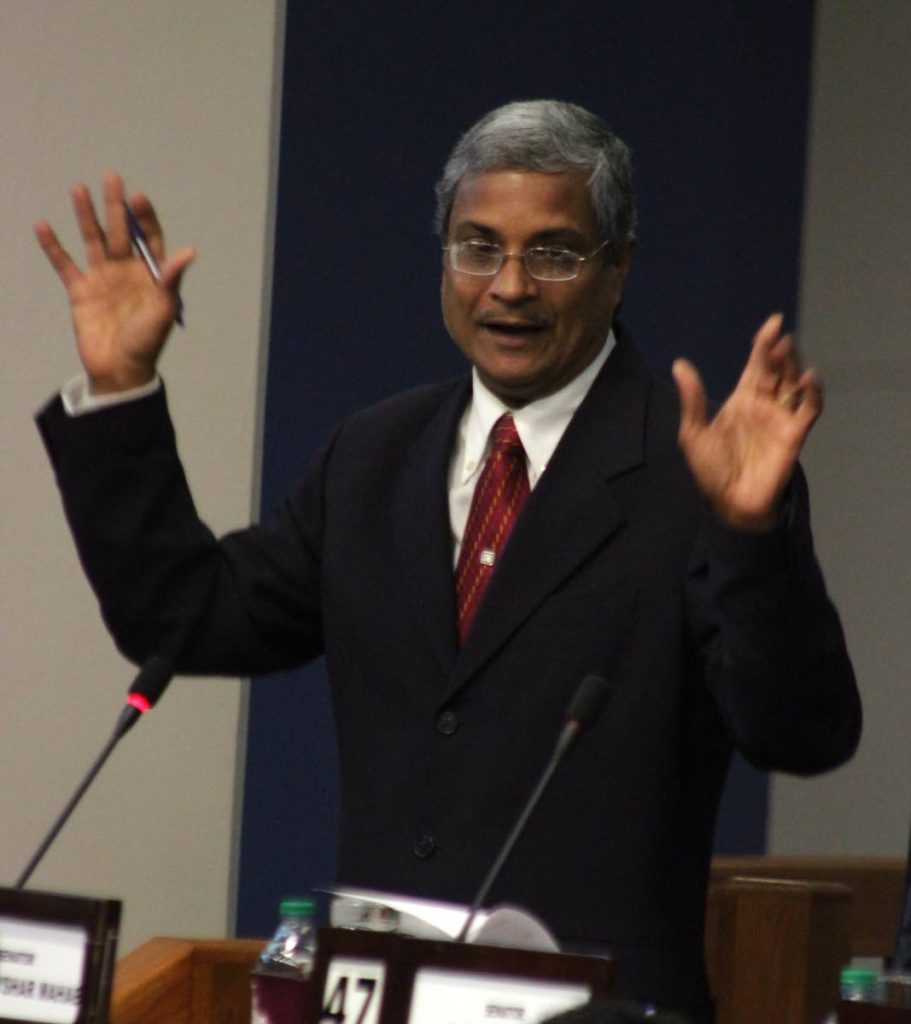

“I also try to persuade public opinion,” one senator opined. And then he surprised us all. Development economist Dhanayshar Mahabir researched French election practice and offered Government an amendment that made an already unpopular runoff proposal even more complex—a third first-round candidate with 25 per cent or more of the vote who fell within five per cent of the leading first-round candidate’s total would also be included in the second-round ballot, creating an élection triangulaire (three-way).

He made headlines. Contributing to a ritual “private motion” Tuesday, senator Mahabir imagined its subject, parliamentary autonomy, might win him a diplomatic passport, medical coverage (not just for parliamentarians earning three times his salary); and an OJT to help write his speeches. “It is undermining my own ability to become a much more effective legislator than I am currently,” he complained. Having recently discovered, in wonder, the Canadian medical marijuana industry, he mused that, in just three months, research staff could help him draft private motions on legalising marijuana, gay rights and abortion. Of course, he was in the headlines again.

There’s a problem, though, with both of these approaches to legislation which highlight weaknesses in Westminster thinking and overlook the simple power of what the constitutional reform sessions achieved. Legislative research can be talking to people on the ground who know the most about an issue and often have been doing action research on it.

Mahabir has been anything but shy about sharing bold opinions and other jurisdictions’ practices during parliamentary debates—more than once on homosexuality—but too often those proposals appear whimsical. Independent senators could take better advantage of local NGOs and universities for research assistance. Friends for Life has been doing action research on working class LGBTI+ lives, and paid to publish some of it in the press last December. The Silver Lining Foundation just launched a sentinel research report on gender-based bullying in TT schools. UWI’s Gender Studies institute and the Caribbean IRN have launched a research e-portal on Caribbean LGBTI+ lives. In 2014, the PNM asked CAISO to prepare a paper on jurisdictions with sodomy laws that protected sexual orientation from discrimination.

But if the Attorney General or Cabinet won’t listen to certain population groups before taking legislative and policy positions, it would be much more powerful for an Independent bench to do so than to look simply at parliamentary practice elsewhere. It is also easy. And free.

Senators can issue invitations or create structured opportunities for consultation and input on issues they find topical that political branches do not. Hold community hours. Legislative solutions to problems must ground themselves locally, and not just re-enact those in other places.

We need stronger links between legislation and lived experience. And perhaps what independent senators can do best is listen impartially to the nation.

Comments

"Triangulaires and OJT legislation"