Shut up, don’t repeat

Institutions, especially public institutions, have rules to help preserve their character and objectives. Parliament is one such institution whose standing orders regarding dress, conduct, speech, etc are jealously guarded by presiding officers and the Parliament itself.

No wonder then that Speaker Bridgid Annisette-George two weeks ago firmly declared in the House of Representatives: “I have noted with grave concern that in-camera deliberations and decisions of, as well as documents presented to the parliamentary committees, have been making their way into the media long before these committees have the opportunity to report to the House.”

This could be treated as contempt, she warned, with possible punishment. Parliament has a traditional range of punishing options, from jailing, suspension, fines to naming and shaming.

A few days after, Senate President Christine Kangaloo made similar remarks to senators.

The challenges for presiding officers have grown in rancour over the years and with allegations and counter-allegations noisily increasing towards next year’s elections, their challenges for order and fairness will grow.

The Parliament’s Standing Order (No 113 in House, No 103 in Senate) seeking to preserve Parliament’s integrity and members’ freedom to deliberate behind closed doors (in camera) states: “The proceedings of and the evidence taken at a meeting of a Select Committee or Sub-Committee and any documents presented to, and decisions of such a Committee shall not be published by any Member thereof or by any other person before the Committee has presented its report to the House.”

That is, members or “other persons” should shut up until the committee presents its report to the House or Senate. Sub-Section 2, however, states: “This Standing Order does not apply to evidence, whether oral and written, taken before a public meeting of a Committee.”

With regard to leakage and premature publication, however, there are two challenges. One is trying to find the “leaker.” Two, journalists rely heavily on not disclosing their sources. The “mailbox” is there. They could be suspended from attending Parliament for any period. It will be world news to jail either member or journalist. The Speaker recently attempted to name and shame. As important as it is for public interest, journalists are there not of right but by the presiding officer’s permission, which may be revoked if the rules are contravened.

These committees, of whatever kind, are fundamentally established for the public interest and part of the accountability required in a parliamentary democracy.

So while the restrictions over premature publication are quite legitimate, what happens when a particular select committee, with a government majority, through its chairman takes an unduly long time to present its report to the House or Senate? Or, for that matter, if a particular select committee fails to have meetings, remaining shut-up for unduly long periods? What is the remedy, especially if the subject matter is of urgent public interest? And this, when the composition of select committees generally represents the executive?

Given my own parliamentary experience, it would not be too far-fetched to suggest that the presiding officers, as custodians of the institution’s rules and integrity, have a role in regularising such matters. There are times when Parliament should have a role beyond the interest of any one party. The blistering issue around the world today, in socialist or more especially democratic countries, is the demand for transparency and accountability

Then by Standing Order 55 (No 53 in Senate), if a member is found by the presiding officer and House to have used objectionable, abusive insulting or offensive words or language and refuses to withdraw or apologise, he may be suspended “for a specific period of time.” That section goes on to include “irrelevant or tedious repetition” made on his own or from what other members said during debate. He too shall be subject to suspension if he refuses to make the advised correction.

In my view, he may make repetition of his own, both for emphasis or, more so, on behalf of his constituents. And this should not be necessarily tied to what other members said. He represents his constituents. However, the Standing Order objects to “tedious repetitition,” tedious meaning “tiresomely long and wearisome.” So really, members may be repetitive, but avoid tediousness, also avoid reading speeches. ( 44.10) It makes the debate boring.

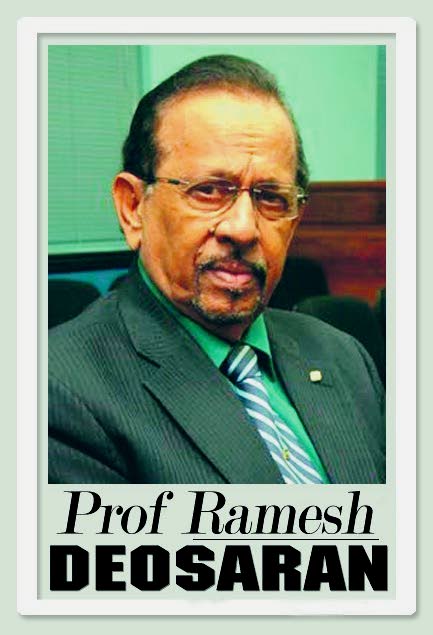

Prof Deosaran, a former independent senator, was chairman of the Joint Select Committee empowered to inquire and report on service commissions and municipal corporations.

Comments

"Shut up, don’t repeat"