Monique Roffey tackles femicide in Passiontide

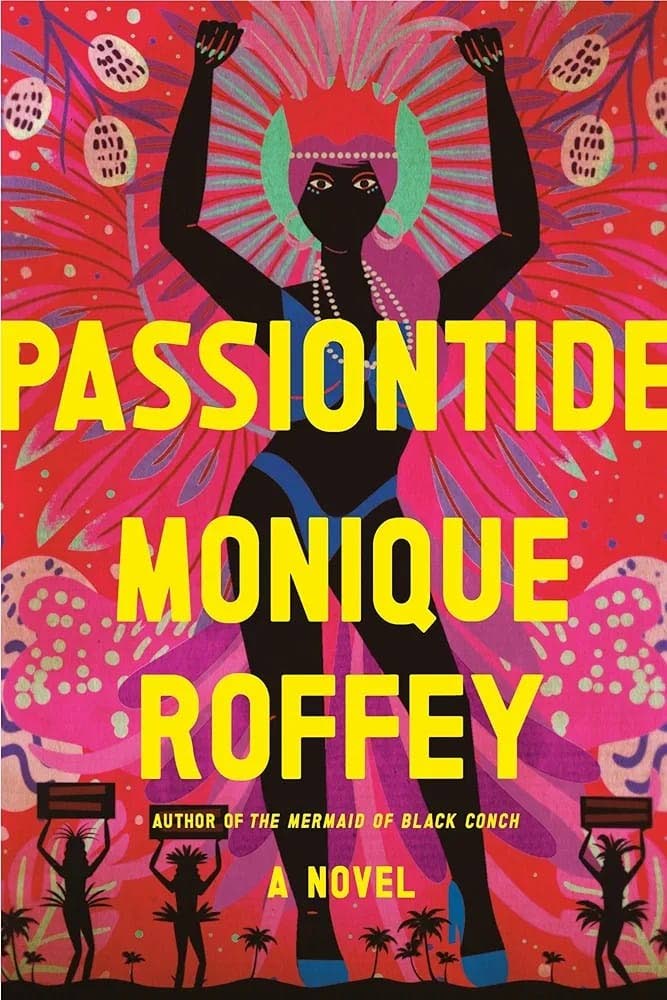

PASSIONTIDE, by Trinidadian-born British writer Monique Roffey, explores the dark depths of femicide on the fictional Caribbean island of St Colibri.

Roffey examines the murder of 23-year-old Japanese pannist Sora Tanaka during Carnival, to cast a light on this much-ignored global issue. She combines feminist and historical fiction with mystery in her genre-crossing novel.

Tanaka’s death sparks a feminist uprising that challenges the fictional island’s historically-defined patriarchy and confronts the growing issue of crime on the island – particularly against women.

The novel presents a sex strike and focuses on misogyny, femicide, race, politics, religion, spirituality and a colonial legacy of violence. It is a compelling read, bizarrely entertaining, as murder mysteries often are, yet provocative and insightful.

Feminists will embrace it; fans of protest literature will revel in its idealism; and historical fiction lovers will compare Tanaka to the real story of 30-year-old Asami Nagakiya, murdered in Port of Spain on February 9, 2016, Carnival Tuesday.

The unsolved murders of both the fictional and real victim she represents go shockingly unwitnessed in a Queen’s Park Savannah filled with Carnival revellers.

Through Passiontide, Roffey sucks in new readers: those of us not usually drawn to feminist literature or novels set in fictitious locations that are thinly disguised real places.

The motley group of women in Passiontide bond over a cause – ridding the island of femicide – but they are not confined to or defined by their anger alone. Each woman has a compelling story. They represent a diverse group: Daisy Solomon, the prime minister’s wife; Tara Kissoon, the activist; and Gigi Lala, founder of the Port Isabella Sex Workers Collective, symbolise individuality and solidarity – virtues sorely lacking on the “real” island represented in this fictional account.

For me, Solomon is the most interesting female character. As the prime minister’s wife, she has status, but she wears a mask to hide the pain, fear and guilt of her sister’s unsolved murder. Her transformation from passive onlooker to active supporter of the women’s movement feels remarkable.

Sharleen Sellier, the journalist, is the only feminist I questioned as a credible character. Her willingness to sacrifice her career for the cause upsets and disappoints me. As a journalist, I see her job as the key to her power. Her editor’s willingness to compromise with her split decisions between work and activism don’t ring true in the world of journalism, which requires dedication and objectivity.

But then, in Roffey’s fictional island, Sellier can explore such contradictory deviations. Non-journalists might view Sellier as choosing commitment and character over career.

Tanaka’s presence ripples through the story, elevating her from a lone foreign figure dying under the cannonball tree to the lofty symbol of a rising spirit watching and commenting on her own life and demise from the branches above.

Her sensationalised murder sparks an all-inclusive feminist movement, with professionals and housewives; women with East Indian and African roots; Hindus and Orisha women led by Makeda Adebisi. The energy of the story comes largely from the exciting buildup of the women’s movement with some jolting images interspersed along the way: harassing and dismissive authorities, and the doubles vendor who arrives at the women’s camp like the Coke-and-fried-chicken vendors who made a sport of black civil-rights cases in the US.

For the men in this novel, the feminists are rabble-rousers and outcasts, a perfect parallel metaphor for local pannists, who historically suffered scorn, but embraced Tanaka as a woman musician. Victim-shaming, inept policing and misunderstood passion propel the novel forward,

Roffey works with strong contrasts throughout Passiontide. Carnival’s gay abandon contrasts with Lent’s prescribed sobering return to spirituality. Police inspector Cuthbert Loveday and his miscreant brother Dunston “Brain” share a murky past, hidden crime and uneasy present. Together the brothers represent the seedy official side of the culture of crime and the underworld, inextricably intertwined.

The men in Passiontide serve as character foils for the women. Prime minister Errol Solomon clings to power and seeks convenient truths; the British pathologist, Dr Jason Forrester, worn out from endless autopsies, seeks escape and meaning in his unconventional relationship with Gigi.

Reality clouds the division between fiction and fact as the investigation hones in on Kurt Vandal, who fits none of the autopsy’s criteria for the killer. Loveday pursues Vandal as a suspect because he’s a convenient scapegoat. The authorities, inept at solving crime, just want to pin the murder on someone to avoid bad foreign publicity and accountability at home. At the height of the women’s protest, an earthquake shakes up St Colibri, literally and figuratively speaking.

It’s easy to get swept away by the energy of Passiontide, but there are many points to ponder as Roffey interjects jolting questions and revelations in this highly-charged novel. How does this fictional story based on an actual person provide a better understanding of the issue of femicide? Why is Tanaka (or Nagakiya’s) murder so symbolic?

Looming large over the pressing issue of femicide is the question of how to affect change in a place riveted by a culture of violence passed down historically through slavery, indentureship and colonialism. Roffey doesn’t merely rehash the past, and she doesn’t permit it to be an excuse for nonaction.

Her insights into leadership are insightful and fair. Roffey writes, “Men like Errol lead the world. Good enough men; not bad men, just limited. His specialty had been ancient history…not contemporary politics; how had he come to rule an island when what he really knew about wasn’t leadership?”

When St Colibri and Solomon are literally shaken to the core by an earthquake, which is ironically fortuitous. it offers Solomon an out, a crack of light, to deal with the women’s seven demands. Smugly, he adds an eighth point, feeling proud of his one-upmanship.

In the destruction caused by the earthquake, Roffey presents the image of the destroyed KFC, a delicious, delightful metaphor for fallen idols representing neo-colonialism. But there’s the ironic twist of fate that comes from Solomon realising the country will need for foreign aid. Is the cycle of foreign dependence doomed to be repeated?

From The White Woman on the Green Bicycle to The Mermaid of Black Conch, a monster hit published during the covid19 pandemic, and now Passiontide, Roffey has earned critical acclaim, international popularity and literary prizes, including the OCM Bocas Prize for her novel Archipelago in 2013 and the Costa Book of the Year (2020) for The Mermaid of Black Conch.

The enigma of Monique Roffey is her extraordinary ability to identify the universality in a particular story – like that of Nagakiya – which she systematically develops into a fictional account with compelling support for the novel’s theme.

Roffey’s voice becomes more and more Caribbean and international simultaneously, a seemingly impossible feat.

Comments

"Monique Roffey tackles femicide in Passiontide"