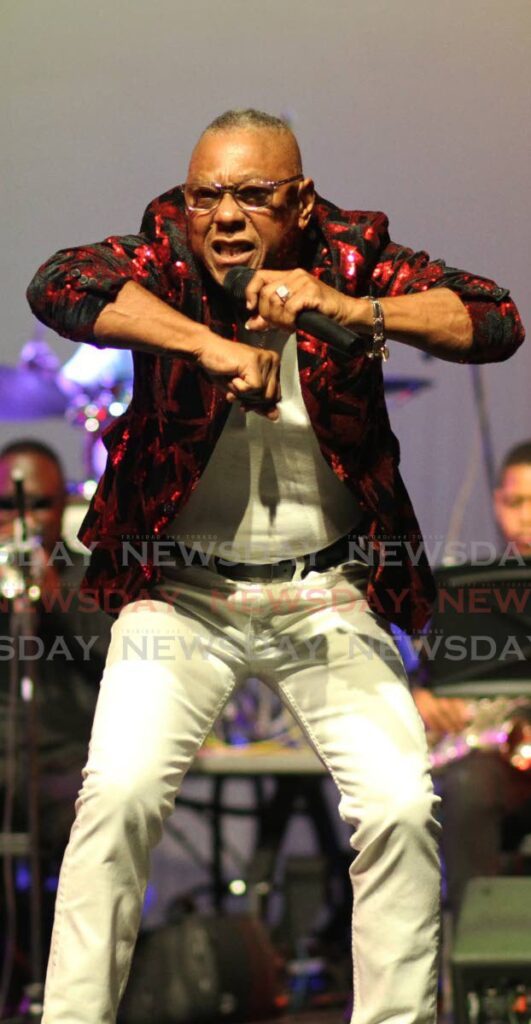

Cro Cro muzzled but not silenced

As the dust settles from another fun-filled Carnival, calypsonian Weston “Cro Cro” Rawlins can’t help but worry about the future.

More calypsonians are “shifting towards soca. They are enjoying themselves, but that’s not how I see kaiso. It’s a serious art form, but people don’t really care. These days it’s jump and mash up the place. Things are happening out there – issues that are affecting us. It will get worse when people like me are gone. I’m not seeing much if anyone at all following in the footsteps of what kaiso is supposed to be.”

Rawlins, the controversial calypsonian who once dubbed himself in song, “The Mighty Midget they can’t muscle at all,” views himself as a caretaker of traditional calypso.

Silence and secrecy are a new look for him, but many of his opinions are only on pause, not muted.

His detractors have dubbed some of his calypsoes as cruel, cringeworthy and racist, but Cro Cro isn’t entertaining their viewpoint.

“The most difficult thing in the world to me is to hate someone. When you hate, your face is always screwed up. Your jaw is grinding. Racism is a big and serious thing that I never entertain. People who think I am racist are selfish and stupid. Some people think I am one of the best things in calypso.”

During the 2024 Carnival season, a High Court judge found Rawlins guilty of defaming businessman Ishan Ishmael in his 2023 calypso Another Sat Is Outside Again, and ordered him to pay $250,000.

“My lawyers have asked me not to comment at all on the case. They begged me to remain silent,” he said.

Cro Cro is not answering any questions about an appeal either. He does admit that he wasn’t expecting a guilty verdict.

“I have confidence in my lawyers, and I didn’t see a guilty verdict coming.”

He quickly added, “No, I don’t think calypsonians are supposed to defame people. The law is the law and you are supposed to respect the law.”

Nothing has changed Cro Cro’s definition of the art form he feels obliged to protect and represent.

“Calypso was born on the plantation as a protest for black people to say something. It’s still something for black people to use to defend wrong things in society.”

In the past, calypsonians hardly thought of the legal implications of their lyrics. Cro Cro’s court case has now set a precedent.

“The verdict against me will make some calypsonians more timid. If this verdict stands, we could lose what kaiso is,” Cro Cro said.

“I’m not saying kaiso should be scandalous or libellous, but kaiso will get a little more conservative now. But then there’s not many people doing kaiso like me.”

Calypso has been Cro Cro’s livelihood since he was 19.

“It’s my profession I haven’t done anything else. That’s why I am one of the best. If I worked at T&TEC, climbed an electricity pole and started to wine, I’d be dead already. My mind would be on songs – not work. You can’t have another job and be a good kaisonian. Suppose you have to go to work and a kaiso hits you at 8 am? You can’t tell your boss, ‘I have to write down this kaiso first.’”

Cro Cro was crowned calypso monarch four times. In 1988 he sang one of his most controversial songs Corruption in Common Entrance and Three Bo Rats, predicting the demise of the ruling political coalition. In 1990 he offered his own version of a Political Dictionary and satirised politics with Party, a double entendre comparing political parties to fetes. In 1990 he won with All Yuh Look for Dat and Deh Cyah Stop Social Commentary. His last calypso monarch title came in 2007 with Nobody Ent Go Know.

“And the judges thief three calypso monarch titles from me too,” he said.

Cro Cro, born in 1952 in Buenos Ayres, Siparia, grew up with a father who worked at Shell oil company and a stay-at-home mother. As a teenager, Cro Cro travelled to Port of Spain to attend school and got two A-level passes in biology and zoology at the Polytechnic Institute. He wanted to be a nurse.

“I put one application in for a job, and they haven’t answered me yet,” he said. “I always have hope they will still call me.”

In 1973, he auditioned to sing in Lord Superior’s tent with Chalkdust and the Mighty Duke.

“They didn’t take me. In 1974 I went to Kitchener’s tent and since then I never looked back. Shadow told me if you can’t make it in five years, forget kaiso. In 1978, I made it to the finals.”

He placed last with Woman Woman and Ling Tang, uptempo songs.

“I was copying Shadow and his Bassman, but I had a problem with a radio station manager who didn’t want to play my songs so I decided to sing for the people who are being oppressed.”

Cro Cro had met Shadow in 1974 when they both sang in Kitchener’s Revue.

“Shadow was good to me. I don’t know what he saw in me. Shadow got big with Bassman and decided to leave the Revue. He wasn’t leaving me there so I went with him to Sparrow’s Young Brigade for two years. We had Kingdom of the Wizards; then the Master’s Den. I was just following Shadow.”

Shadow always told the story that after he lost the calypso monarch title with Bassman in 1974, he found Cro Cro crying and sitting on a curb in Port of Spain.

Cro Cro’s version differs slightly.

“When Shadow lost the competition, he got hysterical and ran. I couldn’t keep up, and I lost him. Eventually, he found me in Independence Square. I was just sitting there because I didn’t know town well. I don’t think I cried.”

He describes himself as “a nice boy to people” but unwilling to take any nonsense.

“I sing for the poor man. They love me for taking a stand and singing songs like Africa Rise and Chop off Their Hand. My message is ‘do good things.’ I’m still growing up and there’s still room for listening, learning and producing more songs.”

But he insisted you won’t hear him in the Calypso Monarch finals again.

“This year I decided I am not going back to the competition.”

That won’t change his direction or his purpose as a calypsonian.

“I lime and I can laugh all day, but if something is wrong I won’t allow someone to chook my eye. You have two eyes so chook your own eye.”

In judging his legacy, Cro Cro said it’s difficult to say if his calypsoes have made a difference.

“I had Put down the Gun but they didn’t put down the gun yet. In Corruption in Common Entrance, they accused me of being racist. The government did an investigation. Ask yourself how did that end up?”

He said he tells people to pray for him.

“But I pray for myself and that’s enough. I sang a calypso about taking my phone and calling Jesus. I have a number for God, you know.”

Faith in God, he said, is all-important.

Cro Cro never envisioned himself standing on the calypso monarch stage without singing, but he ended up there for Machel Montano’s performance of Soca is Calypso on Dimanche Gras.

“I shocked those judges in the Savannah,” he said. “They didn’t expect to ever see me there again.”

When Montano called him just two days before the calypso monarch finals and swore the calypsonian to secrecy, Cro Cro obliged and silently retrieved the school uniform he wore to sing Corruption in Common Entrance in 1988.

“Machel told me this is a big secret,” said Cro Cro, “so I told no one I was going on stage with him when he performed for Calypso Monarch. As a senior in calypso, I told myself I had to do it.”

Cro Cro, dressed as a schoolboy in a short-sleeved shirt, tie and short pants and Daniel “Trinidad Rio” Brown, bare-chested, stood on either side of Montano as the soca singer sang how either calypsonian could have been his metaphorical musical father.

Only silence was required of Cro Cro. He served as a symbol – not a prop.

“I felt proud,” Cro Cro said. “I felt tall.”

He also felt rooted in his convictions more than ever.

Comments

"Cro Cro muzzled but not silenced"