Langston Roach builds legacy of black enterprise

In TT in the late 1960s and early '70s, despite independence, it wasn’t largely believed that an Afro-Trinidadian had the acumen to run a business, hold positions of corporate power or even a managerial position.

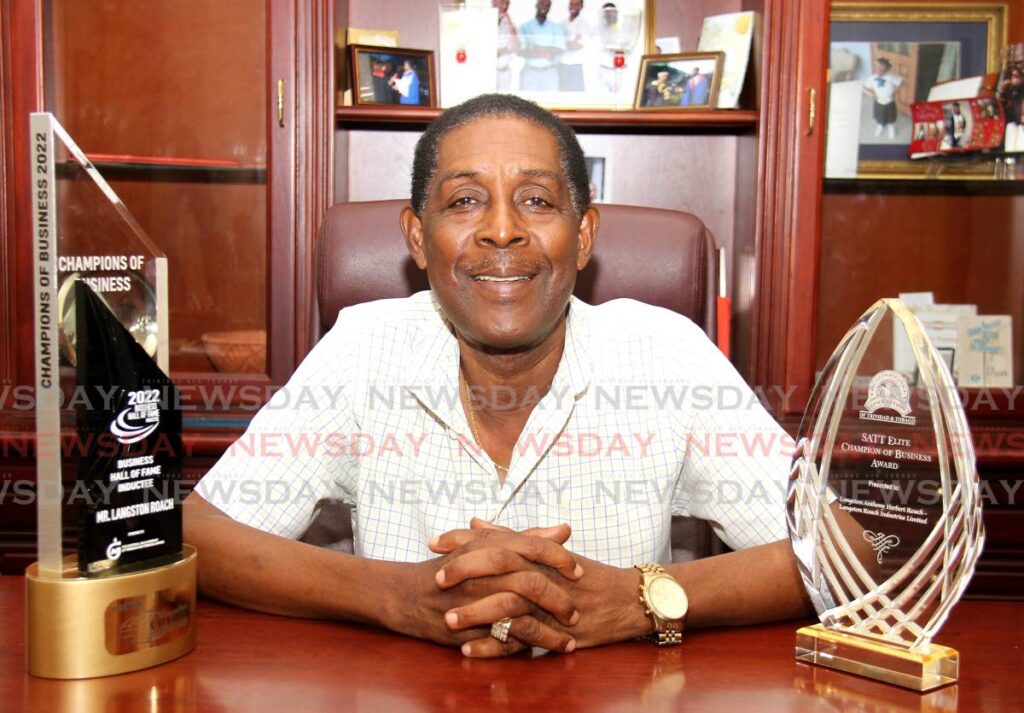

This was how Langston Roach Industries chairman, Langston Roach, now an inductee in the TT Chamber of Industry and Commerce Business Hall of Fame, saw the environment at the start of his journey as an entrepreneur.

In Roach’s acceptance speech at the Chamber’s Champions of Business award ceremony on November 24, he told the audience this perception was one of the things he wanted to dispel.

“At the time it was believed that a black man could not run a business. I wanted to prove them wrong,” he said.

Now, with a list of accolades to his name, including a honorary doctorate from the University of TT (UTT), a Supermarket Association of TT Elite Champion of Business award, and four children who have embarked on their own entrepreneurial journeys, Roach has become what no one thought possible – a successful businessman.

Something to prove

Roach told Business Day that he got his entrepreneurial spirit from his mother’s side of the family. His mother, Veronica, was a nurse until she got married and had children. As a stay-at-home mom, she always found some way to bring an income into the home to supplement Roach’s father’s public-service salary.

Roach recalled seeing his mother work into the wee hours, doing pattern-designs, dressmaking and baking cakes for weddings or selling home-care and beauty-care products. He said she went on to own an Afro-West Indian boutique in Port of Spain, while he, his brothers and his sisters helped her design cakes for customers at home.

“My mother would earn enough money to renovate our house and support me while I was in university, which my father could not do on his own,” Roach said. “My father figured out a way to pay the mortgage and put food on the table and do the basics. So I was aware from an early age that you could work on your own and earn money to support yourself or at least supplement your household income.”

His grandfather, whom villagers at his mother’s home town in St James called Mr Lynch, also set this example. He was a mechanic but was the man to call if there was ever a need in the area to get transport as well.

While studying chemical engineering at the University of the West Indies in 1969, Roach realised that blacks in TT were still considered less than equal despite seven years of independence. The same sparks that ignited the Black Power Movement between 1969 and 1970 also ignited his entrepreneurial spirit.

He was a member of the UWI student guild when students led by Geddes Granger (Makandal Daaga) staged protests against incidents of racism against Caribbean students at the Sir George Williams University in Montreal, Canada. Then governor general of Canada, Roland Mitchener, was set to visit the UWI campus to cut the ribbon to a new wing of the university, Canada Hall. He was instead met with protesting students and a locked gate.

“Having taken a stance against the ill-treatment of the students in Canada and blocking Mitchener off the campus, the guild turned inward and started looking at TT society,” He said. “We realised that black people were being locked out from number of areas in the society.”

“If you went into a bank or an insurance company or any of the big companies in 1969 or 1970, the only black person would be a messenger, not even a clerk. We looked inward and started talking about this and marching about this and that is how the Black Power Movement escalated.”

Roach realised that at the time the culture among black families was to go to school, get an education then get a job, while families among other races taught their children about business and encouraged them to either continue in the family business or set out on their own.

“We didn’t have that period of tutorship in business,” he said. “They would see their parents as a mason, a wielder or a carpenter in a little shop. But when they saw the kind of work that they were doing, after they got their passes they would say they were not doing that, because the business never grew to a level of sophistication where an educated person could see it as a career. I wanted to change that.”

Meeting a crossroads

Roach left the university in his fourth year without completing his degree and set out to start a business. Still the prejudice against black ownership followed him; so much so that when he told his father that he wanted to get into business, his father said, “Why don’t you go and look for a job.”

“I didn't want to do that. I wanted to earn in my own income. Because then I could set my own limits – or rather there will be no limits set on me by anybody else,” Roach said. “When you are working for somebody limits are set on you. A person will only pay you a portion of what you're worth, otherwise their business would not make a profit.”

Roach said he looked for a business that would not require a large amount of capital to start. He chose a discount club – building membership for businesses who would get a discount card. His discount club, Caribbean Corral had about 2,000 members, but eventually went belly up.

“What happened was the business people stopped keeping their end of the bargain,” he said. “People came in with their card to get their discount, but they would be told that the item was already on sale. So the members came back to me and they were quarrelling that they weren’t getting the discounts they were promised.”

“I realised there was a flaw in the process because we could not compel the businesses to give the membership their discounts and we couldn’t take them to court for five per cent on a $100 bill. There was a weakness in this system and so I folded it up.”

He then turned to imports. He imported a product that would dispense cereals and other items. But those products sold slowly.

“People preferred to put their things in a jar and can just take it out. So after a while that went belly up.”

In his third effort, he went back to his knowledge of direct selling. He got a deal with Black Heritage – a cosmetic company which he said was owned by Jews in New York. His franchise saw significant success going from $10,000 in sales to $100,000 in a matter of two years, but after a dispute with the owners the brand was pulled.

“That brand was about 80 per cent of my sales,” he said.

That business also folded.

“I was at a crossroads,” he said. “Here I was, I promised myself in 1970 that I was going to prove this myth wrong; I was going to be a successful businessman and 15 years later I wasn’t just unsuccessful, I was broke.”

“I remember closing my businesses in Port of Spain, going to my home in Santa Cruz and sleeping through the entire weekend. There was no communication. I just got up to eat and then I went back to sleep. I was just dealing with myself and my thoughts and how I would do in the future. I extended that weekend into two weeks.”

“I went over in my mind what is it that really wanted to do with my life and the answer came up the same – I wanted to be an entrepreneur.”

The Langston Roach difference

Roach went back to the drawing board. After some thought, he decided he would go into cleaning products. In 1985, under the Langston Roach Industries name, he began buying products wholesale and re-branded it. He started by going to supermarkets and door-to-door. While the supermarkets turned him away, saying that the brand was not known, residents accepted it. He said for the next 28 years, Langston Roach Industries sold its products door-to-door, bringing in significant income for Roach and the people who worked for him.

“We have people who grew their children up by going around, selling these products door-to-door,” he said.

Roach set high standards, seeing his only competition as major importers such as Unilever. He ensured his products were of the highest quality, and affordable – about 15 per cent lower than the established brands. He convinced supermarkets to buy his products and put them on the shelves while representatives continued to go door-to-door. He also had representatives in the supermarkets to help push sales.

If there were complaints about the products he would go back to his garage-based operation at his home in Santa Cruz and using his knowledge in chemical engineering he changed the formula to meet the customer’s satisfaction. Eventually, the products, which he branded as Lanher, were so popular that he didn’t need representatives at the stores.

He also sought to empower his employees, paying door-to-door salespeople at a higher rate than most jobs at the time. He continued the door-to-door sales programme until 2013 – even though he had a factory – out of concerns over crime.

Now, Langston Roach Industries has grown from a small Santa Cruz cottage business to one that has 200 employees.

“We started off in my garage in Pax Vale, then we moved to a 4,000 square foot place in El Socorro, then we moved to an 8,000-square-foot place. Now we are in a 70,000-square-foot location and it’s too small. We just rented an additional warehouse in El Socorro to hold the overflow of products.”

His legacy continues in his sons. Roger Roach is the founder and CEO of Lazuri Apparel Ltd, which won this year' TT Manufacturers Association's Exporter of the Year award in the SME category. Jason Roach runs industrial supplies company – Rojan Marketing – and Sean and Ian Roach manage the operations at Langston Roach Industries.

Roach advised aspiring entrepreneurs to never consider themselves as small nor as failures. He said, whenever things do not go the way as planned, take the time to heal and start again.

“I have never been a small businessman. I've been a businessman who started small and grew that makes a difference. I've never considered myself to be a failure. Things didn't work out, I asked myself, 'What did I learn?' and I start again.”

Comments

"Langston Roach builds legacy of black enterprise"