The Windrush generation – some facts

Last week I received an urgent message from my great niece in London. When did I first arrive in the UK? Her six-year-old daughter Amira was invited to the unveiling of a monument to the Windrush generation and she needed a short brief on her family connection.

I quickly wrote back that there was none since I did not arrive in the UK on the famous MV Empire Windrush in 1948 that brought a capacity load of unemployed Caribbean men, mainly Jamaicans, some with their families, to Britain to work in the post-war recovery effort. That was all before I was born and, in my estimation, none of our family qualified technically, at least, to that economic or social classification. In fact, I was not the first of my mother’s family to travel to the UK, which I did in the late 1960s as a youngster. They had been moving between TT and from whence their ancestors came for decades. And, I did not regard myself as an immigrant, since I sought education, not work. But time and circumstances would change how all dark-skinned Caribbean people were described by others.

My great niece's message took me back. When I arrived, the attitude to race was benevolent, at least, in my apparently isolated operating sphere, because there had been nationwide race riots in 1919, in 1958 in Notting Hill and Nottingham, and in the 1960s in the Midlands and elsewhere, plus, the signs on rental property that said “No Blacks, No dogs, No Irish” were legendary. Yet, I experienced no racism, not anywhere I went. I was never discouraged or turned away from any pursuit, incredible as that may sound, rather, I was encouraged and given extraordinary opportunities to make my way, which I did, in spite of flaunting my Trinidadianess.

From the 1940s to the 1960s the influx of Indian, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis and West Indian immigrants grew exponentially, causing a backlash especially in areas where English people were experiencing economic hardship. Race and immigration became bitter social and political issues, peaking when in 1968 a leading Conservative MP made an alarming speech, predicting “rivers of blood” in British streets. Victimisation grew and parliamentarians passed a series of immigration laws that largely ended immigration, till in 1972 General Idi Amin of Uganda expelled all Indians for “milking” the country. Thousands of them, with British passports, added to the already large numbers of black and brown faces that had become too familiar on British streets. Riots erupted throughout the 1980s.

The Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, largely non-English speakers, fared badly while the Indians, especially the well-educated Ugandans, many of whom later returned to their prosperous homeland, floated to the top and began to organise. Caribbean intellectuals, unionists and other activists who had been at work since the 1950s as the numbers swelled and the violence burbled, formed pressure groups. They lobbied for and achieved anti-discrimination legislation. Anti-racism quangos and organisations at all levels arose. In academia race became an area of study. In the Caribbean communities, people began to organise too. In the mid-90s, “The Windrush Generation” had been dubbed. It threatened to rewrite history, though that had not been the intention of the two ex-WWII servicemen (Windrush returnees) who believed that by creating the Windrush Foundation they would bring attention to the role Caribbean people played in the new Britain.

In response I made a programme for the BBC in the mid-1990s about the pre-Windrush generation, to prove that the West Indian or Caribbean presence in the motherland predated 1948 and that the post war referencing of a generation was being opportunistically used to discount what had gone before. We know that Caribbean men served in two world wars to defend the Empire, many died, 3,000 remained in the UK after 1945, others returned on the Windrush, having found the Caribbean in a dire economic straits. British-Nigerian David Olusoga’s excellent Black and British: A Forgotten History, published in 2016, takes the reader back some 2,000 years of the black presence in Britain. It is a history that has been deliberately suppressed by British historians and urgently needed to be corrected. For my pre-Windrush programme, I discovered several, by then old, Caribbean servicemen, with their English wives and totally British families. I remember one, particularly, who had settled in Liverpool and owned a club where he encouraged the Beatles, in their early days, to do gigs and develop their music.

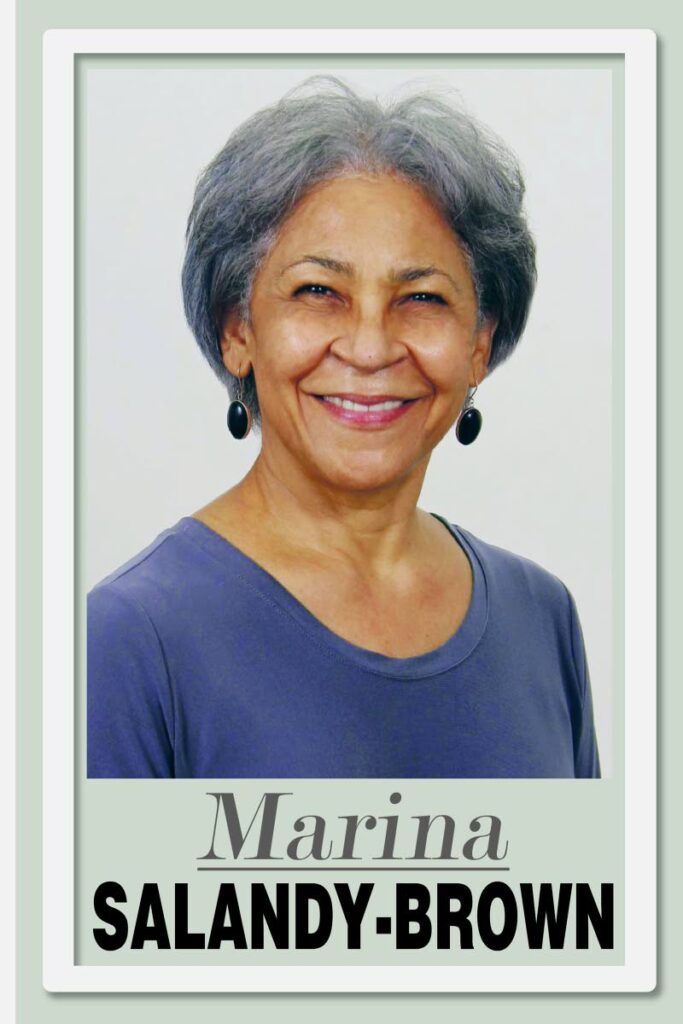

Amira starred on the front page of a British newspaper last week, photographed speaking with the Duchess of Cambridge at the unveiling of the most beautiful commemorative sculpture in Waterloo Station. She had got there because Floella Benjamin, the Trinidadian actress, now Baroness Benjamin, had published Coming To England, about growing up in post-Windrush Britain. Amira played the part of Floella in her school’s dramatic adaptation of the book. Amira’s grandmother, Clary Salandy, Artistic Director of the UK Centre for Carnival Arts (UKCCA) who designed the carnival costumes for the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee parade and knows Baroness Benjamin, sent her a video clip of the rehearsals and Floella, thrilled, invited Amira to join her at the ceremony. We are all well and truly now part of the Windrush generation.

Comments

"The Windrush generation – some facts"