A foundation for learning

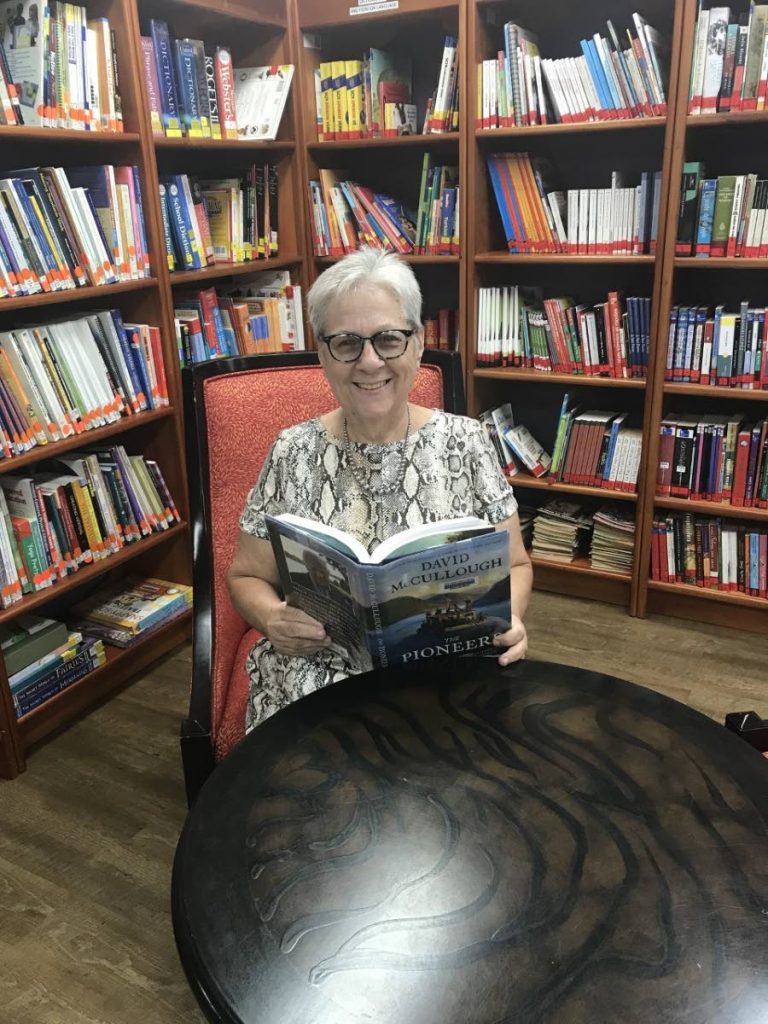

I AM OFFICIALLY retired from my school library now, but looking back on my 26 years of working as an English teacher and librarian makes me realise how my past experience with students and books provides an important lesson for this covid19 crisis that defines the present. From day one as an educator I learned that reading is the foundation of education. It’s time we realise that as a nation.

Education is facing challenges like never before. Even in the best-case scenario with schools open throughout the tough year ahead, students are bound to be facing disruptions in their education as schools with covid19 cases close to sanitise after outbreaks and sick students stay home to avoid infecting other students.

The only constant students can possibly have in their lives is reading, which provides intellectual stimulation, boosts critical thinking skills, offers emotional support and provides a much needed escape from the pressure and uncertainty that prevails.

The Government can talk about providing computers all it wants, but if there’s nothing else that covid19 has taught us, it is that we have to simplify our lives and get back to basics. We have to consider a level playing field for all students, and that can best be achieved by providing a robust reading programme through schools, libraries, businesses and community centres. I know this is possible because in the past Children’s Ark and my Wishing for Wings Foundation offered a programme where inmates read to their children in the Sterling Stewart library in the Port of Spain Prison. We are now working on setting up zoom reading sessions for inmates and their children.

I now have past students in their 40s, and they still reminisce about the books they read when they were 16. We didn’t have a wide variety of young adult (YA) literature then, but we used relevant literature to explore the world and their interests. My students, from 45 different countries, proved united in their interests. Strong characters, interesting plots and relevant conflicts could grab students’ attention.

There were so many wow moments. The boys enjoyed Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte more than the girls did, but they both enjoyed learning about the first Mrs Rochester in Wide Sargasso Sea by Dominican writer Jean Rhys. These books sparked heated discussions about cross-cultural love. The Ginger Tree by Oswald Wynd examined the concept of love in Japan. My Japanese friend Masako Chen visited my class for those discussions. I once had a book club for Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind. The girls dropped out, but the boys stayed to make a detailed study of Rhett Butler’s sex appeal.

Magical realism opened up a whole new world for my students, which they first discovered in Strange Pilgrims, a collection of short stories by the late Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez, who described himself as a Caribbean writer from Aracataca on the Caribbean coast in Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza’s book The Fragrance of Guava. A short story from that book, Light is Like Water, about a group of schoolchildren who flood an apartment with light, inspired students to make a short film. My students read Of Love and Other Demons and News of a Kidnapping by Garcia Marquez so they got a feel for how journalism shaped Garcia Marquez’s fiction writing.

Oh, there were so many wonderful books. I once had a class of eight 14-year-old boys who were off the charts in their maths skills. They loved reading too. With no girls in the class, they devoured Robinson Crusoe, Moby Dick, Oliver Twist. I never required reading more than 20 pages a night, but these boys read 80 pages a night. They devoured books. The discussions and essays made me feel like I was teaching a university class.

The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy provided invaluable lessons in structure and form and Cry the Beloved Country by Alan Paton presented the theme of apartheid in South Africa. Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad and an essay by Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe about why Conrad’s novel was the most dangerous and racist book ever written sparked heated discussions about racism.

In one essay we studied, South African’s Steve Biko argued why white people should stay out of black people’s struggles for equality while Nadine Gordimer argued that justice is everyone’s struggle. Over time, my book choices became edgier, much to my students’ delight.

The point is I found books that created memories and provoked thought. I created a foundation for learning. We need that more than ever.

Comments

"A foundation for learning"