Love is stronger than death

VAHNI CAPILDEO

You would be mistaken if you ignored Kei Miller’s new book, In Nearby Bushes, just because it is poetry and perhaps you do not read, like, or understand poetry. It is worth reading if you are regularly horrified by the news, and cynical about society’s redeemability. It is also worth reading if Caribbean landscapes, or landscapes anywhere, hold beauty or intrigue for you.

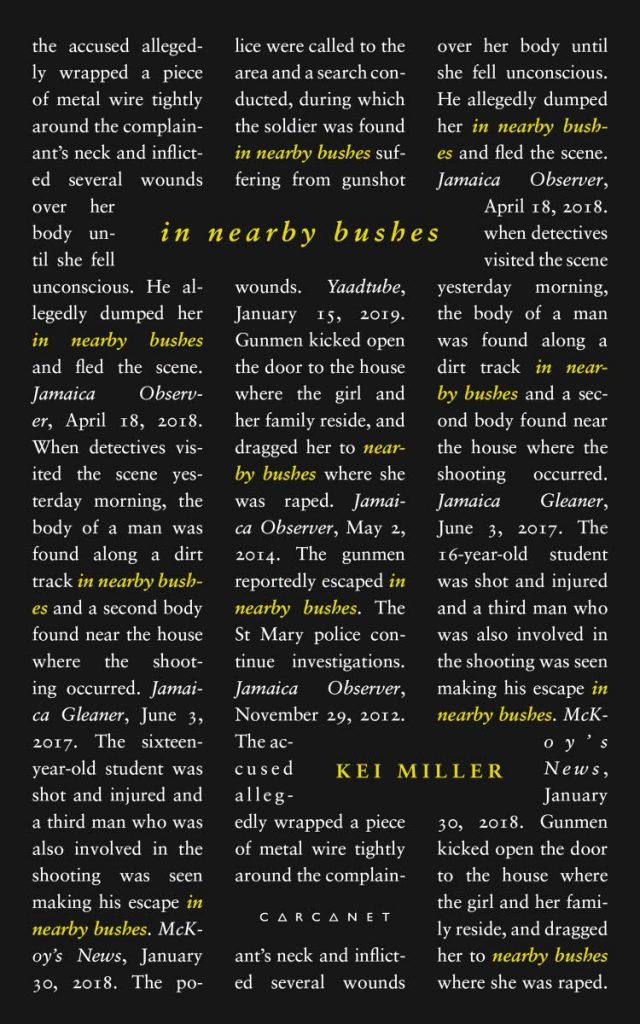

Never judge a book by its cover. Nonetheless, the cover of the Jamaican literary superstar’s 2019 offering seems designed for judgement. Night-black, the front features three columns of white and yellow words, unnerving as a photographic negative or what you see when you close your eyes.

These columns reproduce quotations from media sources such as the Jamaica Gleaner, Jamaica Observer, McKoy’s News, and Yaadtube. The white-coloured words quote reports of rape, murder, and fugitive behaviour. The yellow words locate these events “in nearby bushes.”

Before you open the book, poetry has been visited upon you, without your consent: the title and subject already haunt you, like a refrain. The back cover emphasises that Jamaica is “a landscape as much marked by magic as it is by murder.”

The contents hold to this promise. If you choose to start reading, you will not get away lightly; but you may be positively transformed.

Poetry is a way of using language without fear of intensity or complexity. It is uniquely suited to deal with our sense of the otherness lurking in everyday life, “in nearby bushes.” Miller, a controversial essayist whose Writing down the Vision won the OCM Bocas Prize for non-fiction, grounds his latest publication in the “real world.”

The book starts with an epigraph from Jamaican blogger Paul Tomlinson’s reproach to the commissioner of police to “go inna the bush and catch” the criminals who “always escaping in nearby bushes.”

In the second epigraph, Prof Anthony Harriott, director of the University of the West Indies (UWI) Institute of Criminal Justice and Security, points out a difference between “in the nearby bushes,” which Harriott associates with “concealment” and “danger,” and “the nearby bushes,” where people enjoy the opportunity to hide their sexual activities or their disposal of bodily or household waste.

Miller explores the full range. For example, the tender truth of A Psalm for Gay Boys celebrates and criticises the equally real joy and hypocrisy of “softness amongst the thorns where the married men roam at night, their trousers unzipped, where we are kissed by the same lips that curse us.”

Then there is the scientific compassion of the volume’s closing sequence, which refuses to present a murder victim as being reduced to an object. Writing about violence can risk becoming a kind of pornography, gloating over squeamish details. This is not the case here, although there are references aplenty to worms and decay, and to medical and folk terminology for injury.

In Miller’s poetic practice, love is stronger than death. Crime is not allowed to blot out the person who suffered the effects of crime. Direct address remains possible: “You had a heart. It stopped. But the thing that was your body did not stop. It only began to do new things,” Miller insists. He pronounces the cadence of absolution: “You are the air, and the ground, and the things that rise to meet you.” This fulfils a crucial task for culture: to reflect on oppression, without repeating the oppression. Miller surpasses expectations for a book to be about something, as if a book’s purpose were merely to convey information, or to create an experience. To read In Nearby Bushes is to be guided into thinking through things, however uncomfortable or uncanny. Poet and reader venture into the realm where “the bushes shiver” in “the sign of some other life behind the leaves, another world inside this world.”

Still, this is a book review, and not a sermon. How does In Nearby Bushes measure up in terms of ambition and technique?

From the beginning, Miller righteously changes the rules. Here Where Once Lay The Bodies arranges into three-line verses the names of people, their reported ages (from nine to 72), and the date their corpse was found. A final line, outwith this pattern, stands in isolation: “& these are only some.”

Despite the organisation into tercets, this composition is not listed as a poem. So, what is it? It resembles a memorial, like a war memorial. It invites the reader to bear these and similar losses constantly in mind, however far individual poems may go in other directions in the Anansi web of this book: legend, anecdote, meditation. Poetry, after all, emerged to help with memorisation, long before the development of writing. In poetry, nearby bushes cannot remain an area of darkness. They constitute peculiar sites of dream, speculation, and memory.

Miller’s structures show traces of traditional and contemporary storytelling and conversation in Caribbean communities, and in the international community of poets. His voice often speaks to the reader, sometimes almost flirtatiously establishing a relationship. “These things I know as much as you,” claims a prose poem about the slow coming of dawn. The loveliness of this poem places us as bodies living through time, but also questions the feeling of simply being in the world. Being seems simple only if we ignore “the specifics.” Moments of wonder are non-naïve, spider-stitched into wider perspectives. When the rogue herd of escaped reindeer which now allegedly inhabit Jamaica’s hills are hailed as “new maroons,” whimsy is balanced with awareness of the historical multiplicity of human and non-human needs to flee into strange habitats.

Much could be said about the excellence of the first two sections of In Nearby Bushes, Here and Sometimes I Consider the Names of Places. These revisit the concerns about who gets to name things and impose borders, and what it means for a place to be a place, which Miller expressed via a dramatic dialogue between a mapmaker and a rastaman with a PhD in his previous collection, The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion. They demonstrate his proven ability to handle lyric, lament, and lecture; to speak of place with an understanding of a million shades of green, and to translate how place speaks: “The trees, sometimes, are grunting.”

The third, final and most powerful section shares a title with the book itself, In Nearby Bushes. It includes a number of newspaper extracts, repetitively reprinted with certain words or letters in bold, and the rest greyed out.

Why does Miller do this? “Erasure poems” currently are popular with experimental poets. They start with “found text” from another source, and selectively blank out most of it. This creates a new poem by leaving a spaced-out set of evocative letters and words.

Miller’s book of memory plays with erasure, but resists blanking out his sources. The greyed-out sections remain readable. If you look at the shape this makes as a whole, it moves like a forest in the wind, dark and light. Is this frustrating? No more frustrating than the forest. If you add up the letters in bold, you uncover messages that remix earlier poems: “Here where blossoms the night.” You unhide the obsessional subconscious of the newspaper extract: “gunshots,” “gunman’,” “gunfire,” “escape,” “escape.”

Here is a wordsearch game turned serious. Here are witnesses to dismemberment, and acts of re-membering. Here is the doubt and hope that a choice that is not mere escapism can be made, moving from “rage” to a “kinder page.”

* Trinidad-born poet Vahni Capildeo won the Forward Prize in 2016. Her new book, Skin Can Hold, is published by Carcanet.

Comments

"Love is stronger than death"