The vision after 2020

KIRAN MATHUR MOHAMMED AND BROOKE HADEED

It's easy to attack politicians. But we raise them. We elect them. The blame must stop. We all know the problems. We can't demand our leaders do a better job if we don’t place that same demand on ourselves. We must hold them accountable, as we must hold ourselves accountable.

It's time to reject the notion of the “lazy Trini” waiting for a handout. We are entrepreneurial by nature – from the man who puts out a chair by an empty lot and charges for parking to the aunty selling pepper sauce out of her kitchen. We are born hustlers. Globally, we are entering the “gig-economy,” where the concept of the stable nine to five job is becoming extinct and everyone is running a side business. Oil giants have been replaced by tech giants. Barbados and Bermuda are talking innovation hubs and digital currency. Why are we late to the table?

We’ve been stuck reading the same chapter of oil and gas dependence but the truth is that our leaders have repeatedly tried to change that narrative. Why did they fail? Since 1962, diversification has been a top priority. But the approach has always been top-down.

Who can blame the great post-independence leaders for wanting to use the levers of the State for development? It was exciting. From Williams to Nehru, they reached for industrial policy, wielding subsidies, raised tariffs and built state-run firms as national “champions”.

The sobering reality came later. Almost every developing country that tried its hand at industrial policy in the 20th century found success the exception, not the rule.

Good industrial policy takes discipline. We couldn’t become South Korea or Singapore – those economies flourished under autocratic governments.

We valued democracy and we weren’t afraid to make noise. We suffered too long under colonialism and we just didn’t want to suffer any more.

Oil & gas cycle

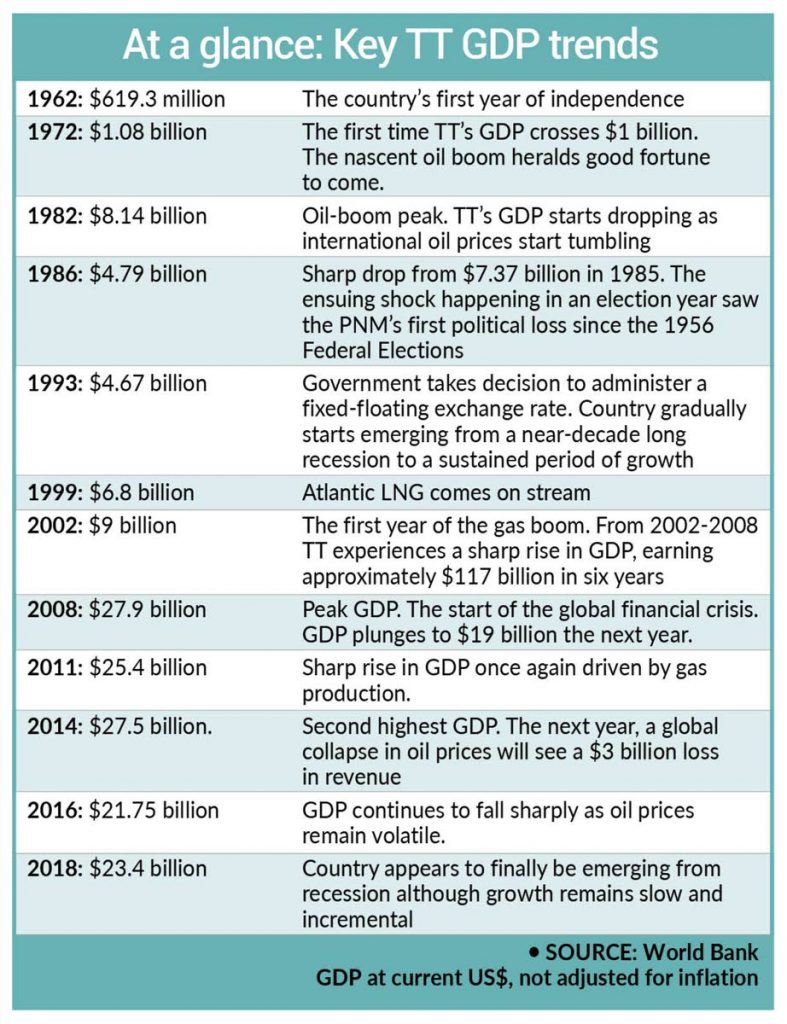

The government started flexing its petro-muscles in 1973: the first oil boom. Subsidies on everything from fuel to sugar laid the foundations of an increasingly paternalistic state. The need to take over declining industries to save jobs quickly became a greater priority than creating new industries. By the end of the seventies, losses from public enterprises were rapidly gobbling oil revenues. Economist Richard Auty reckoned that public sector employment expanded from less than one-quarter to more than one-third of the total workforce.

When it seemed that oil revenues were set to decline, in 1978 a new hope emerged: natural gas. But this wasn’t just extraction. We downstreamed and processed, becoming the world’s leading exporter of ammonia and methanol. This was diversification in action.

When the economy boomed once more between 2002 and 2008, it was all about Vision 2020, our guide to becoming a developed nation by…next year.

The Vision 2020 National Strategic Plan was laid before Parliament in 2006, highlighting the “need to develop innovative people; nurture a caring society; enable competitive business; invest in sound infrastructure and environment; and promote effective government.”

The plan called for a “psychological and attitudinal revolution” of the entire nation. This country has never had a problem with rhetoric. Saying all the right things comes easy. Following through is the hard part.

It seemed that Vision 2020 was doomed before it started. A 2007 Readiness Assessment Survey involving 23 ministries found “widespread disregard for the preparation of logical frameworks; monitoring agencies could not ensure that their recommendations were implemented; performance evaluation was not widely used in decision-making; and there were deficiencies in reliable, valid and timely economic and social data to track progress towards the achievement of the goals of Vision 2020.”

Plans fail when decision-makers are not held responsible for their choices. They fail when those decision-makers don’t have the facts. They fail when the people on the ground don’t have the facts either. Fifty-seven years on, where are we now? Where do we go?

Plans fail when decision-makers are not held responsible for their choices. They fail when those decision-makers don’t have the facts. They fail when the people on the ground don’t have the facts either. Fifty-seven years on, where are we now? Where do we go?

Our country is filled with brilliant minds. Young people want to grow. But they’re stuck in childhood bedrooms. They might have a smart idea: but who is going to give a loan to a kid with no collateral? What if there is a way out of this dilemma? One that acknowledges the silent forces that have held back our economy.

AI – the new normal

The next chapter in our economic story will be defined by trust and confidence. “Every commercial transaction has within itself an element of trust" stressed Nobel economist Kenneth Arrow. According to the 2014 World Values Survey, TT ranked last place in the world – only 3.4 per cent of us trust one another.

We cannot grow without trust. That is how business works. The doubles man trusts us to finish bussing up our channa and barra before we pay him.

Breaking a half-century cycle of mistrust will not be easy. But technology is doing just that. Platforms like Airbnb and Amazon allow information to be easily shared. They allow us to easily rate people or resolve disputes, so that we think nothing of staying in a stranger’s home or buying from a seller thousands of miles away.

Then there is confidence. When people are confident in the economy, they spend more and take more risks. Not only do we lack confidence in our economy, but also our leaders, and worse still, in ourselves.

If we think we can never be more than oil and gas, if we think we will always be subject to poor governance, if we think our children will never succeed because they didn’t pass for a “prestige school”, then sure enough, those prophecies will be fulfilled. This is no time to feel hopeless or pessimistic.

World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab has proclaimed the fourth industrial revolution. The world, he says, will be changed by artificial intelligence, robotics, the Internet of Things, autonomous vehicles, 3-D printing, nanotechnology, biotechnology, materials science, energy storage, and quantum computing.

This isn’t science fiction. And it’s not just for rich countries. These new technologies are fast becoming the new normal, and developing countries stand to benefit. It’s already infiltrated our lives without us realising. Fifty-seven years later, we haven’t lost the race, it has only just begun.

Kiran Mathur Mohammed is a social entrepreneur, economist and businessman. Brooke Hadeed is an economist and international development consultant. Brooke and Kiran are Global Shapers, an initiative of the World Economic Forum.

Comments

"The vision after 2020"