Driving to our demise

The 2018 budget statement presented a fleeting, yet eye-opening, bit of data that I suspect many missed; a glimpse into a reality that we clearly haven’t taken seriously. In 2017 alone, TT used up roughly US$500 million in foreign exchange just to import vehicles.

In late 2017, it seemed like I could rarely browse social media sites without being bombarded by a targeted advertisement from a particular local car dealership, for its latest year-end promotion. These ads are typically so common as to be forgettable. But, right there, in no uncertain terms were the startling words, “no down payment, no instalments until the new year, and no credit score check”. They were making it easier to buy a car than to rent an apartment, although the monthly payment for the former could’ve proved more expensive.

In 2015, according to the International Energy Agency, our transportation sector used 0.8 tonnes of oil equivalent per capita, compared to 0.2 tonnes in Jamaica, 0.4 tonnes in Brazil, and 0.6 tonnes in the United Kingdom. Houston, we’ve got a problem; albeit one that we were warned about from a mile away. Many countries that have travelled this impassable road have counselled of the futile journey. But I suppose we, with our macociousness, need to see the landslide, fallen trees, and eroded pitch; take a picture; and broadcast to all of our friends and family, before we decide it’s time to turn around.

What more will it take for us to accept that we have an expensive and debilitating addiction to cars and driving, and seek out rehabilitation? The treatment begins with an acknowledgement that our assumptions about progress and what constitutes logical urban and transportation planning need to be reassessed.

The presence of highways, overpasses, and expensive and oversized vehicles, is a false positive in the test of progress. In the words of Gustavo Petro, former mayor of Bogotá, Colombia, “a developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It's where the rich use public transportation”.

The studies exist and are easily accessible for validation, but did we really need them to know in our hearts that the more time we spend driving, the higher our stress, anxiety, rage, and animosity towards one another? These aren’t characteristics associated with happiness, a high quality of life, and a nation on the path to progress. That’s without even mentioning the studies that directly relate increased time spent commuting by car to increased incidences of domestic violence, increased political apathy, and deteriorating physical health. We really aren’t being honest with ourselves. We’d like to pretend that we can change our trajectory of increasingly failing state, without fundamentally changing anything at all about our lifestyles.

Just this week, we tragically lost another pedestrian life on the Diego Martin Highway. I was disheartened, but not surprised, to read the overwhelmingly callous comments on social media blaming the pedestrian for not using the walkover to cross the road. A line that I too, once upon a time, may have uttered in private company.

But, think about it, how often do you drive over the 50 kilometre per hour speed limit around the Savannah, refuse to stop at a crosswalk or stop-sign, or take a shortcut through a dangerous neighbourhood or along a treacherous road to get to your destination faster? Risk-taking is just as human as taking precautions. None of us is infallible; driver, cyclist, or pedestrian. Let’s evolve from victim-blaming, to asking ourselves the deeper questions. As the authors of the 2004 book, Urban Sprawl and Public Health, would probably say: some would list the cause of death as blunt force trauma, but perhaps we should also label it as death by poor urban planning and form.

We should be questioning why highway conditions separate the residential from the commercial areas of a community, requiring its residents to navigate an inhospitable environment, just to get anywhere useful using the most sustainable form of transportation, their nature-given two legs, and, why the genius and socially-acceptable solution to these uninviting environmental conditions is to install expensive, hideous, heat radiating walkovers that double or sometimes triple the distance it takes to cross a road, and that many don’t use here or in any other country.

The reckoning that our planning and transportation-based paradigm is a catastrophe, is overdue. It happened to me in my very first course in planning school. I was stripped of all of my ingrained, conceited, baseless notions of how urban areas should function. I survived the blow to my pride and am here to tell the tale, but also here to take you through the same life-changing and humbling process.

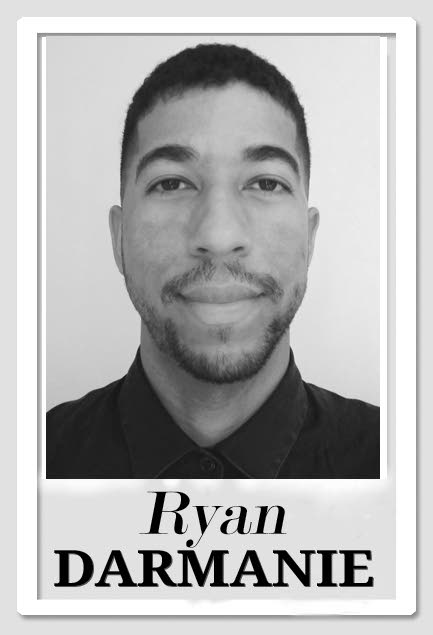

Ryan Darmanie is an urban planning and design consultant with a master’s degree in city and regional planning from Rutgers University, New Jersey, and a keen interest in urban revitalisation. You can connect with him at darmanieplanningdesign.com or email him at ryan@darmanieplanningdesign.com

Comments

"Driving to our demise"